Events in the Piazza

1288

The Storming of Palazzo del Popolo

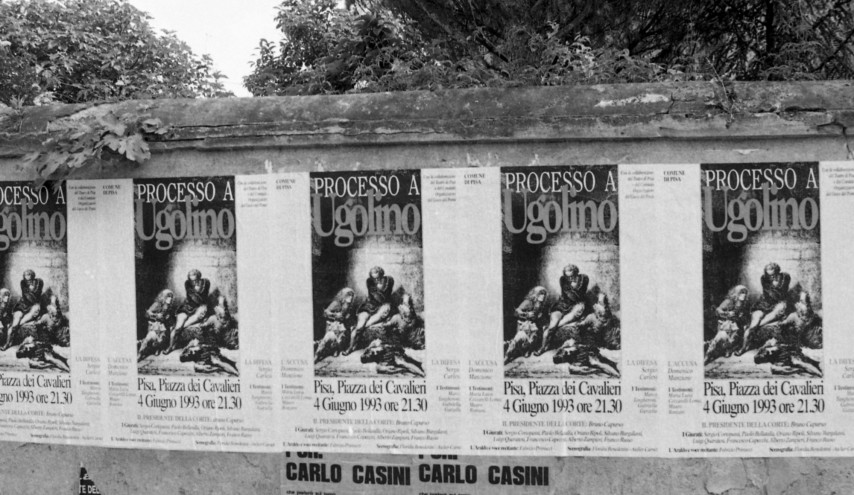

In 1288, the Capitano del Popolo, Count Ugolino della Gherardesca was defeated by the Ghibelline faction led by Archbishop Ruggieri. Near-contemporary sources tell us that the soon-to-be Piazza dei Cavalieri was the setting for both the initial negotiations and the violent armed clash that followed. The episode culminated in Ugolino's imprisonment and death in the Tower of Famine, events immortalised in Dante's famous verses.

Throughout the Middle Ages, as communities continuously redefined the uses and meanings of their public spaces, Piazza dei Cavalieri (known by the toponym ‘delle Sette Vie’ before the early modern period) served as an arena where the factions driving the Commune’s political life engaged in armed conflict. The metonymic expression ‘prendere la piazza’ [to seize the piazza], found in some ancient chronicles, indicated the military occupation of the city’s administrative centre and thus its political control. Perhaps the most notorious case concerns the clash that led to the imprisonment of Ugolino della Gherardesca and his family members. The most ‘sharp-tongued’ source (to use Mauro Ronzani’s apt expression), is the Fragmenta historiae pisanae, which describes the episode in great detail. Written probably at the end of the thirteenth century, this anonymous chronicle narrates the events of Pisa from 1190 to 1293 (with an appendix focusing on the period 1327-1336). The only manuscript preserving it is the Additional 10027 in the British Library, while a printed copy comes to us from the scholar Ludovico Antonio Muratori, who published the text in his work Rerum Italicarum Scriptores. Although it is difficult to make well-founded hypotheses about the author’s identity or the circumstances of the text’s production, various narrative details (particularly regarding responsibility for the prisoners’ deaths) suggest an orientation not particularly hostile to Ruggieri and the Ghibelline front.

In October 1284, Ugolino was elected podestà, a position that would be exceptionally granted to him for ten years just a few months later. His nephew Nino Visconti worked alongside him, becoming Capitano del Popolo in 1286. After a turbulent period of shared leadership at the helm of the commune, the two leaders exchanged roles: Ugolino became Capitano del Popolo, moving into the magistrate’s palace in the Sette Vie area, while Nino became podestà. On 30 June 1288, while Ugolino was at his castle in Settimo in Pisan territory, Nino was driven from the city (likely with Ugolino’s support) by a Ghibelline coalition led by Archbishop Ruggieri, who installed himself in the Palazzo del Comune. The count rushed back and began delicate negotiations over future governance arrangements in San Sebastiano alle Fabbriche Maggiori (on the site where Santo Stefano dei Cavalieri stands today), which continued until the first of July. The Fragmenta reports: The aforementioned count and the archbishop were together in the church of Santo Bastiano on the morning of the first of July, and they did not reach agreement in the morning and were to return after nones [‘lo dicto conte, e l’arcivescovo l’autro die di calende luglio la matina funno insieme in de la chiesa di Santo Bastiano, e non s’acordonno la matina, e doveanovi tornare di po’ nona’]. During a break in the meeting, news spread that Brigata, Ugolino’s nephew, was trying to open the city gates to Tieri Bientina, the count’s son-in-law, who led a company of a thousand armed men. The opposing faction’s leaders, fearing treachery, engaged in bitter armed conflict.

The retelling of the confrontation opens with a striking acoustic observation: the bells placed on the towers of the two highest magistracies rang out in support of the warring factions: the ‘People’s’ bell, housed in its eponymous building, rang for Ugolino while the bell of the Palazzo del Comune (located in Piazza Sant’Ambrogio, in the area of present-day Piazzetta Lischi, formerly known as del Castelletto) rang for the archbishop. Fighting on foot and horseback spread through the streets surrounding the square: San Frediano, San Sebastiano (now identifiable as Via Consoli del Mare) and ‘l’autre vie’ [the other streets] ). The battle was bloody: there were several notable casualties (including Archbishop Ruggieri’s nephew), and it lasted about half a day (‘da di po’ nona in fine a presso a di po’ vespero’ [from after nones until nearly after vespers], i.e., from past midday until sunset). The Ghibelline forces eventually prevailed over the count’s men, who were forced to retreat. Count Ugolino, barricaded himself with his family inside the Palazzo del Popolo (or Palazzo degli Anziani, specifically the right wing – as viewed from the front – of what is now Palazzo della Carovana), faced the final phase of the conflict. Ruggieri’s loyal men (the entire population of Pisa, according to Giovanni Villani’s chronicle) finally stormed the building ‘with fire and brute force’ [‘con fuoco, e per battaglia’ ], overcoming the last resistance and imprisoning the ‘traitor’ count and his family members.

1292

Feast of the Assumption

The proceedings of the Feast of the Assumption are documented in municipal records from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. On the eve of the Feast, a procession would set out from the lavishly decorated square later known as Piazza dei Cavalieri. The procession followed the Anziani and the Capitano del Popolo—Pisa's highest magistrates—to the Cathedral for the presentation of ceremonial candles.

The Feast of the Assumption was undoubtedly one of medieval Pisa’s most important solemnities. Following an ancient Christian tradition, it celebrated the ascension into Heaven of Christ’s mother, the Virgin Mary. The sources that provide detailed accounts of both the preparations and formal celebrations include the Annali pisani (Pisan Annals) compiled by the seventeenth-century scholar Paolo Tronci, as well as a series of official documents preserved in the Archivio di Stato di Pisa and the Archivio dell’Opera del Duomo. In a notable contribution to Italian historical scholarship, Pietro Vigo offered a precise and insightful reconstruction of this key aspect of communal life in an 1882 text, which he later incorporated into a broader volume published in 1888. His reconstruction drew partly on archival sources and partly on Tronci’s description of the feast, which he dated to 1292.

As with the Corpus Christi procession, public institutions exercised pervasive oversight of the two-day Assumption celebrations (the vigil on 14 August and the main celebrations the following day). While the exact origin of these celebrations remains unclear, municipal decrees concerning them continued throughout the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The celebrations were announced by public proclamation well ahead of time, though sources vary on the precise advance notice given. Twenty young citizens, who paraded through Pisa’s streets in two parallel lines, were charged with this task. ‘They wore extremely rich clothing of a rather bizarre form’ [‘abiti ricchissimi e di forma assai bizzarra’], while their horses were covered entirely in scarlet cloth bearing the Community’s arms [‘coperti tutti di panno scarlatto con le armi della Comunità’]. The first pair of youths carried the flags of the Comune and the People, the next pair bore the imperial standards, while the third pair carried two live eagles symbolising the Republic. The procession concluded with a retinue of trumpeters and pipers.

The future Piazza dei Cavalieri was crowned with flags on the day of this proclamation. According to Tronci (though Vigo disputes this), the banners of the Commune, the Capitano del Popolo, and the imperial eagle were displayed on all the city’s towers (which he claimed numbered sixteen thousand). This practice was also observed at the seats of civic magistracies, including the Palazzo degli Anziani.

According to the documents, the piazza served as the starting point for an elaborate procession on the eve of the feast. From here, the Anziani and the Capitano del Popolo would be escorted to the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta for vespers. The Anziani proceeded ‘with great pomp and majesty’ [‘In gran pompa e maestà’] led by ‘young attendants dressed in new livery, and trumpeters accompanied by the Capitano with his retinue and all other lower magistrates’ [‘donzelli vestiti di nuova livrea e così i trombetti accompagnati dal Capitano colle sue masnade e da tutti gli altri inferiori magistrati’].

Another central aspect of the ceremony was the ‘offering’ of candles (in reality, a mandatory contribution required from all citizens, as well as from the boroughs and villages of Pisan territory) to be deposited at the Cathedral on the eve of the feast. As Vigo notes, ‘three days before the Assumption, the Podestà would prescribe to everyone, under penalty at his discretion, to present their candle at the Cathedral, so that all offerings would be brought there in the customary order’ [‘tre giorni prima dell’Assunzione, il podestà faceva prescrivere a ciascuno, sotto pena da darsi a suo arbitrio, di andare a presentare al Duomo il proprio candelo, affinché tutte quante le offerte fossero quivi recate nell’ordine consueto’].

Even the form of the candles to be provided by the highest magistracies was carefully prescribed by public ordinances. The documents reveal vivid details: the ‘candeli’ were transformed into complex artistic creations through the work of specialised craftsmen. They were painted and decorated with figures, and often embellished with banners and fringes. The candle of the Anziani—likely the most elaborate—was adorned, for example, with ‘fringes and standards’ [‘fimbria et pennones’] .

The ceremonial presentation of candles at the Cathedral involved an elaborate procession: although specific references are lacking, it is reasonable to suppose that the procession offering the Anziani’s candle began from the Piazza delle Sette Vie. Placed on a ‘trabacca’ (which Vigo identifies as a pavilion likely mounted on a cart to protect the candle from the elements), it was accompanied by twenty-six men, paid for the occasion by the Commune, and trumpet players.

These accounts of the Assumption celebrations show that the urban landscape, later transformed under the Medici, served as a central stage of Pisan social life of the republican era. The piazza hosted the city’s most significant ceremonies, which embodied the communal ethos and reinforced both the harmony among different powers and the unity of the civil and religious order.

These documents and celebrations reveal a piazza in constant transformation, its character shaped by its varied uses. The decorations, symbols, temporary stages, processions, and shifting crowds created an ever-changing scene: though the physical space remained unchanged, its appearance was perpetually renewed.

1312

Enrico VII and the Turris leonis

To commemorate Emperor Henry VII's visit to Pisa in 1312, he was given a lion, probably by the Comune. In the following decades, the city continued to cover expenses for maintaining a lion in the town (though perhaps not the same lion that was given as a gift). This commitment by the city magistrates has suggested identifying the animal's place of captivity at the future Piazza dei Cavalieri, where a Lion's Tower (Turris Leonis) was documented during those same years.

At the turn of the fourteenth century, Pisa found itself in a precarious position. The city was burdened by harsh peace terms imposed after its defeat by Genoa at Meloria (1284), threatened by land from the Guelph cities of Florence and Lucca, and challenged at sea by the papacy, which, in alliance with the Aragonese crown, sought to strip Pisa of its control over Sardinia. Given these circumstances, the Commune placed its hopes in Henry VII.

Henry, elected emperor in 1308, immediately declared his intention to lead a campaign in Italy. In spring 1310, he sent ambassadors to Pisa, as he did to other cities, to assess the situation before his descent into Italy. In this climate, the Pisans, in March 1310, turned to Federico da Montefeltro, one of Italy’s most prominent Ghibelline leaders, granting him extraordinary powers through the combined offices of Podestà and Capitano generale of the Comune. By doing so, they were renewing a relationship with the Montefeltro family that had been established through Federico’s father, Guido, who had ended the joint rule of Count Ugolino and Nino Visconti.

In that same year of 1310, as soon as he crossed the Alps, Giovanni Zeno Lanfranchi and the jurist Giovanni Bonconti went to meet the emperor to offer him Pisa’s unconditional support. In November, other Pisan citizens travelled to the court at Asti, where they took their oaths as royal counsellors.

Pisa’s hopes for Henry’s arrival were openly displayed when he reached the city on March 6, 1312. The Emperor arrived by sea from Genoa, making his first stop at the important pilgrimage sites at San Pietro a Grado. From there, he proceeded to the city, where at the city walls, he was greeted by the citizens who presented him with magnificent gifts: a purple canopy studded with gold and gems (as described by the chronicler Ferreto Vicentino) and a precious sword. Waiting to welcome ‘Alto Arrigo’ (‘Noble Henry’), as Dante would call him (Paradiso, XXX, 137), were not only the citizens of Pisa but also the cream of Tuscan Guelph exiles. Among them were likely the famous poet himself and the young Petrarch, accompanied by his father.

The first residence to host Henry was the archepiscopal palace near Pisa’s primatial church, which was opened to him by the archepiscopal vicar Enrico da Montarso. On March 17, documents were drawn up formalising the emperor’s complete control over the city. These granted him the power to appoint the Anziani (city elders) directly and required oaths of loyalty from both the Commune’s magistrates and all citizens. The ceremonies marking this transfer of power were held in front of the ecclesia maior of the Blessed Virgin Mary. A few days later, however, Henry moved his court to the south of the city, taking up residence in the elegant palace of brothers Gherardo and Bonaccorso Gualandi in the Chinzica district.

Despite the wealth of information surrounding the emperor’s two stays in the city, no notable events are recorded as taking place in what is now Piazza dei Cavalieri, even though this nerve centre of Pisan political life must surely have witnessed public celebrations and ceremonies in the shadow of its palaces. However, it is important to note a detail recently brought to light by historical studies: the appearance, among the court’s expense records during the Pisan stay, of payments for maintaining a lion, recorded on March 28 and April 15 (before Herny’s departure from Pisa on the 23rd of the month).

The beast was likely presented to the emperor as a diplomatic gift from the Pisan Comune, carrying clear symbolic value of royal dignity. Significantly, the only other living lion kept in the city during the fourteenth century and recorded in sources was an animal owned by the Comune, documented in 1317 and 1337. Two provisions from those years concern the maintenance of a lion, and the second one (July 18, 1337) specifically mentions ‘a messenger of the Pisan Comune’schamber’ [‘nuntius camerae pisani Communis’] who ‘gave and must give food to the lion of the Pisan Comune’ [‘dedit et dare debet pastum leoni pisani Communis’]. Pio Pecchiai, who discovered these documents in the early twentieth century, connected the reference to the lion with a ‘Turris leonis’ documented in 1330 near Piazza degli Anziani (later Piazza dei Cavalieri). Though the place name might simply reflect a heraldic emblem, the reference remains plausible. This raises the intriguing possibility that during the imperial stay in Pisa, a lion given as a gift to Henry VII was kept near the central square of civic power, similar to other symbolic animals raised in the square’s buildings, such as the eagles in the Tower of Famine. The name Torre del leone remained in use for some time, although court expense records tell us that the lion given to Henry accompanied him to Rome, where it disappears from royal accounting records.

1355

Public Convictions and Executions

In late May 1355, while Charles IV of Luxembourg was in Pisa, Piazza del Popolo was the scene of a brutal and isolated episode tied to the city’s newly reasserted political authority: the public sentencing and execution of those deemed enemies or traitors of the empire.

The triumphal entry into Pisa in January 1355 of Charles IV, King of the Romans and soon-to-be emperor, was followed by an oath of fealty sworn to him by the institutional bodies of the Pisan Comune. As a direct consequence, he assumed the role of guarantor of civic peace and justice. It is therefore unsurprising that one of the first measures enacted under his authority was an edict requiring all citizens to submit petitions concerning any wrongs suffered directly to him.

Over the following months, Charles’s powers expanded—thanks largely to the support of the Raspanti, a city faction that had backed him from the outset—culminating in his formal recognition as Lord of Pisa and Lucca by a specially convened council. These developments are clearly documented in the writings of Ranieri Sardo, the principal local chronicler of Charles’s time in Pisa.

When Charles returned to Pisa in May 1355 from his coronation in Rome, accompanied by his wife, Anna of Świdnica, he found the city in turmoil over reports that Lucca had broken away from Pisan control. It was against this backdrop of unrest that a dramatic episode unfolded. On 26 May 1355, following their conviction for treason and for plotting to assassinate Charles IV, Francesco, Lotto, and Bartolomeo Gambacorta—sons of Bonaccorso and vocal opponents of the Empire—were publicly beheaded in the Piazza del Popolo (later Piazza dei Cavalieri). They met this gruesome fate alongside Neri Papa, Ugo Guitti, Giovanni delle Brache, and Cecco Cinquina. The executions took place in front of the Palazzo degli Anziani (later Palazzo della Carovana).

The sentence, issued by the court of the capitano del Popolo, Mellino da Tolentino, is preserved in a document long known to scholars. According to Ranieri Sardo’s Cronaca di Pisa, the condemned were led from Via Santa Maria to the foot of the staircase leading to the municipal palace, where the judgment was read aloud before they were beheaded in front of the assembled Pisan crowd.

Matteo Villani, in his Cronica, described the events similarly, adding that the condemned ‘were led in their shirts, bound with cords and belts, and, like the vilest of thieves, pulled and dragged by boys, were thus ignominiously conducted from the Cathedral of Pisa to Piazza degli Anziani’ [‘furono menati in camicia cinti di strambe e di cinghie, e a modo di vilissimi ladroni tirati e tratti da’ ragazzi, furono così vilmente condotti dal Duomo di Pisa alla Piazza degli Anziani’] .

The episode is also recorded in the Cronica di Pisa (MS Roncioni 338, Archivio di Stato di Pisa), where an anonymous author offers a shorter account and dates the events to 28 May rather than 26. Centuries later, Jacopo Arrosti adopted the same date in the first book of his Cronica di Pisa (1654). Clearly, within the rich fourteenth-century historiography of Pisa, the episode was considered so extraordinary that it became a defining and indispensable reference point for narrating the exercise of imperial lordship over the Commune in the mid-fourteenth century.

Ranieri Sardo also records that in August 1397 (Pisan calendar), another member of the Gambacorta family, Carlo di Gherardo—a canon of the Cathedral—was sentenced to death in Pisa’s main square. Unlike earlier members of his family, he was not accused of offending imperial majesty, but of repeatedly conspiring with the Florentines to seize castles in the Pisan countryside—an episode also noted by the Florentine author of the Cronica volgare, formerly attributed to Piero di Giovanni Minerbetti.

The execution, however, did not take place in the square but at the ‘mercato delle bestie’ (livestock market) on the morning of 12 August, five days after Carlo’s capture and imprisonment in the Citadel.

An order was then issued across the city forbidding anyone from approaching the bodies, which were initially meant to remain on display in the square until 29 May. Further valuable testimony comes from Giovanni Porta da Annoniaco’s Liber de Coronatione Karoli IV Imperatoris, who reports that the executioner had been instructed to act without delay to prevent any attempt by the Bergolini—another Pisan faction—to rescue the condemned. This urgency may explain why the bodies, instead of remaining on display for the planned three days, were left exposed for only an hour, after which Charles granted the citizens permission to bury them.

Whilst sources indicate that the public reading of sentences at the foot of the staircase leading to the Palazzo degli Anziani occurred on multiple occasions (Sardo, for instance, records a financial penalty announced in this manner in January 1398), executions in Piazza del Popolo were far from routine. The case of the three Gambacorta brothers and the four members of the Popolo faction in the late spring of 1355 was highly exceptional, driven by the particular political circumstances arising from the emperor’s presence in Pisa.

1361

Feast of Corpus Christi

First documented in 1361, the Feast of Corpus Christi in Pisa featured a procession that began and ended at the Cathedral, winding its way through various streets and passing through the future Piazza dei Cavalieri, the city's political heart. This symbolic connection between Piazza del Duomo and Piazza dei Cavalieri gave the medieval community a powerful image of unity and harmony between the Commune’s governing powers.

During the Middle Ages, religious festivals – in Pisa as in many Italian city-states – were central to community life. Their significance can often be gleaned from the meticulous detail with which public ordinances, accumulated through decades of legislative activity, regulated even the most minute aspects of these elaborate and rigorous ceremonies.

Documents relating to civil and religious authorities’ deliberations, particularly from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries (preserved in the Archivio di Stato di Pisa), reveal a strong determination to formalise rituals crucial to civic life: every detail was carefully regulated – from offerings and official dress codes to the organisation and pathways of processions. Notably, the path winding through the city’s streets and squares was designed to symbolically embrace political and religious power centres, reflecting a concordia ordinum fundamental to the commune’s civic religion. Within this framework, Piazza degli Anziani or del Popolo, later known as Piazza dei Cavalieri, became an essential stop on all civic ceremonial routes.

According to the anonymous fourteenth-century Cronica di Pisa, the first celebration of the Feast of Corpus Christi took place on May 27, 1361. The same source attributes its establishment to the ‘Operaio of Santa Maria Maggiore, who went by the name Ser Bonagiunta Masca’ [‘Operaio di Santa Maria Maggiore, il quale avea nome Ser Bonagiunta Masca’]. Eight days before the feast, heralds employed by the Anziani (city elders) would ‘with the sound of trumpets’ summon the city’s inhabitants: ‘All persons, men and women, must go on the morning of the Feast of Corpus Christi to the Duomo, the major church, and accompany the Body of Christ in procession’ [‘ogni persona, maschi e femmine, debbiano andare la mattina della festa del Corpo di Cristo a Duomo, alla Chiesa maggiore, e alla processione accompagnare lo Corpo di Cristo’].

All participants were required to carry a candle, whose size was strictly determined by the bearer’s social rank: private citizens typically carried half-pound or one-pound candles (‘according to their means’), while the Anziani carried two-pound candles. The procession began at the Primatial Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta, continued along Via Santa Maria, and then likely detoured through what is now Via dei Mille. From there, it entered the Piazza, paying tribute to the city’s political heart, before continuing on a route that would return it to the Duomo: ‘And they departed from the Duomo along Via Santa Maria, to Piazza delli Anziani, through the Borgo, along the Arno by Piazza delli Pesci, and the Ponte nuovo ; and then, following Via Santa Maria, they returned to the Duomo’ [‘E si partì di Duomo per Via Santa Maria, ed alla Piazza delli Anziani, e per Borgo, e per di Lungarno dalla Piazza delli pesci, e del Ponte nuovo; e per Via Santa Maria tornonno a Duomo’]. The direct connection between Piazza del Duomo and Piazza dei Cavalieri conveyed a powerful image of unity and harmony between the commune’s governing powers.

According to the witness’s account, the procession’s centrepiece was the host (for Catholics, the symbol of Christ’s Body) enshrined in a golden tabernacle carried by the archbishop. The head of the commune’s religious authority was accompanied by the Cathedral’s canons who held ‘a fine silk pallium’ [‘un palio di seta drappo fine’], followed by the highest secular officials: the Anziani, the Podestà (chief magistrate), the Capitano del Popolo, and the Imperial Vicar. The procession concluded with ‘men and women, adults and children of the City’ [‘uomini e donne grandi e piccoli della Città’].

From the account, we learn that this ceremony was preceded ‘When the Sun had risen two hours’ [‘Levato lo Sole a due ore’, i.e., at around eight in the morning] by a procession of ‘Friars and Priests and all the Companies of the Flagellants of the City of Pisa, and then the Archbishop of Pisa’ [‘Frati e di Preti e di tutte le Compagnie de’ Battuti della Città di Pisa, e poi l’Arcivescovo di Pisa’]. The Flagellants were members of lay civic confraternities who practised penitential self-flagellation: ‘And all these Flagellants went about whipping themselves while wearing sackcloth, each with their own standard’ [‘E tutti questi Battuti andavano battendosi col sacco in dosso, ciascuno col suo Gonfalone’]. Although one might reasonably assume that this earlier procession followed the same route as the main one and therefore passed through the Piazza, the chronicler is not clear on this point.

1382-1383

Supplicatory Processions to Ward off the Plague

To stem the relentless plague that afflicted the city between 1382 and 1383, the city magistrates took responsibility for both the permissions and expenses needed to transfer the relics of Saint William of Maleval from Castiglion della Pescaia to Pisa. Here, after a solemn blessing in the Cathedral, they were preserved in Palazzo degli Anziani (later the Palazzo della Carovana) and became an object of devotion for the citizenry.

From 1348 onward, the Black Death maintained an endemic presence in Italy, its catastrophic periodic resurgences affecting every urban centre across the Peninsula. Pisa was no exception; after 1348, it endured violent outbreaks in 1362, 1372, 1382-1383, and 1391. Among these, the plague that raged from the summer of 1382 through the autumn of 1383 provides a particularly valuable lens through which to examine how the city responded to the spread of the disease and what forms of spirituality it turned to, as this outbreak was described in meticulous detail in the anonymous Cronaca(known as Roncioni), dating from the late fourteenth century.

During Pietro Gambacorta’s rule over Pisa (1369–1392), he took on the titles of Capitano di Guerra (War Captain) and Difensore del Popolo (Defender of the People), roles that underscored his leadership during a period when Pisa’s communal institutions were in decline. Although the city’s republican governing bodies continued to function nominally, Gambacorta had effectively become Pisa’s leading authority.

Since the limited sanitary measures proved inadequate against the contagion, the Commune and ecclesiastical authorities united in promoting spiritual practices they believed would best secure divine intervention and deliverance from the plague. The anonymous chronicler lists multiple processions that took place from October 1383 onward, with the participation of the people, clergy, and civic magistrates, including the college of Anziani, the Podestà, and the Capitano del Popolo. As Cecilia Iannella has rightly observed, the processional route likely followed the one described by the anonymous chronicler in his account of the first Corpus Domini procession, which took place in Pisa in June 1361. It began at the cathedral, continued along Via di Santa Maria, and then reached the ‘piassa delli Ansiani’ – that is the urban space later known as Piazza dei Cavalieri – then along the Borgo and following the Lungarno (the embankment along the Arno River) westward to the bridge, where the procession turned back onto Via di Santa Maria to return to the Duomo.

The communal institutions did not limit themselves to participating in religious processions. According to both the anonymous chronicler and later sources, the Commune itself took the initiative to seek papal permission for transferring Saint William of Maleval’s relics from Castiglion della Pescaia to Pisa and subsequently organising a series of religious events to secure the protection of the saint, who was believed to guard against the plague. On August 4, 1383, the relics entered the city through the Porta San Marco. On 4 August 1383, the relics entered the city through Porta San Marco. They were received by the Anziani, city clergy, general populace, and companies of flagellants. Among these groups, the Compagnia di San Guglielmo held particular prominence. This confraternity, likely established during the 1372 plague a decade earlier, commissioned the beautiful processional banner by Antonio Veneziano that is now preserved in the National Museum of San Matteo.

After the procession, the relics were taken to the Cathedral for a solemn mass, meticulously described by the chronicler; however, following the celebration, the chest containing the remains was transferred to Palazzio degli Anziani (later Palazzo della Carovana), where it remained, guarded day and night and secured by two keys, one held by the prior of the Anziani, the other by the abbot of the hermitage of San Guglielmo at Castiglione. The processions were repeated during August – from the 10th through the 13th and again on the 18th. Each followed the identical route, concluding at the Cathedral, where a solemn mass was celebrated and the relics were displayed. According to the chronicler, these ceremonies gave rise to numerous miraculous healings and exorcisms.

However, the same source specifies that between 16 and 18 August, the relics were displayed morning and evening for public devotion at the Palace of the Anziani, ‘in della chiostra giuso che vvi si fecie uno altare, e quine si mostravano le ditte erelique’ [in the lower cloister where an altar was erected, and there the said relics were shown]. This makeshift shrine in the semi-public space drew crowds of faithful citizens: some came with monetary offerings, others brought candles, and many approached to kiss the bier, each seeking the saint’s healing power. The relics were returned to Castiglione on 26 August; nevertheless, in Pisa, the cult of the hermit saint persisted for a long time, as evidenced by iconographic sources and the survival, until the eighteenth century, of the confraternity dedicated to him.

The funeral of podestà Jacopo da Bologna, who died during the 1382 plague outbreak, provided another opportunity for communal institutions to demonstrate their leadership role. The Commune funded the ceremonies, which centred on a procession – evidently the most common expression of the bond between the citizenry and its institutions – from the Palazzo del Podestà, where the body lay in state, to its final resting place in the church of San Francesco.

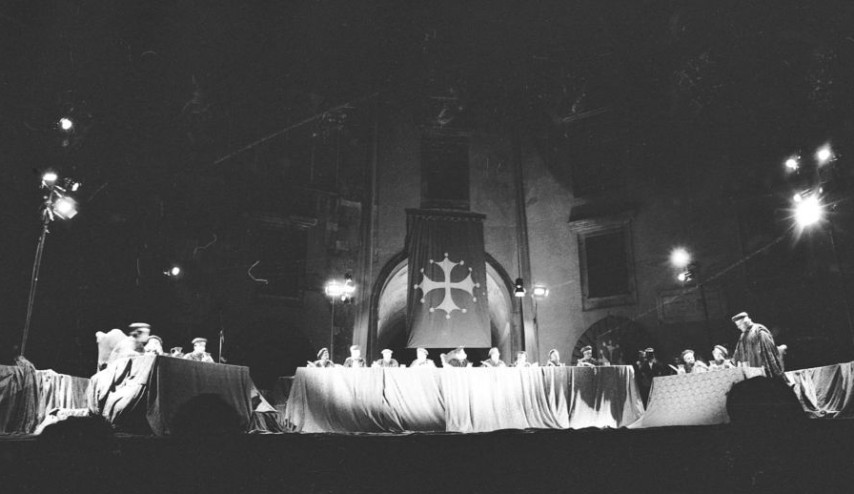

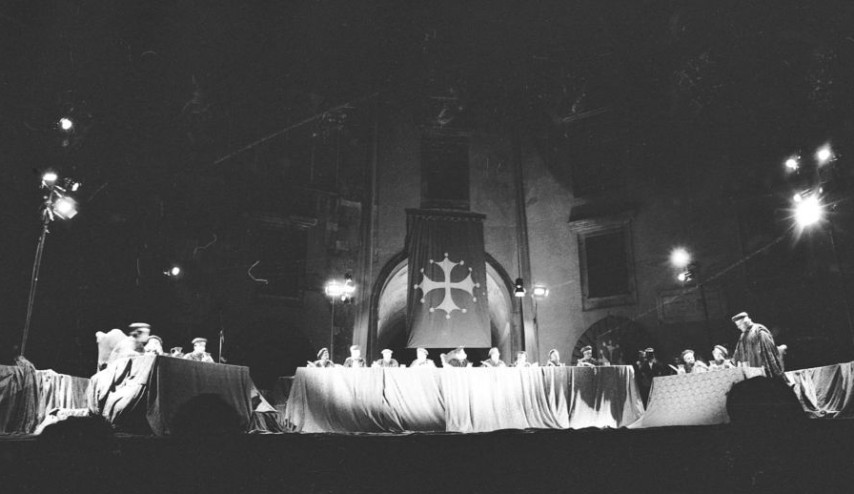

Media gallery

1406

The Last Celebration of the ‘Gioco del Mazza-scudo’

From at least the mid-twelfth century, a recurring carnivalesque festival with a martial theme, known as the Gioco del Mazza-scudo ('Mace and Shield Game'), was held in the future Piazza dei Cavalieri and, at times, in other parts of the city. Involving the male population of Pisa, the event was already regarded in earlier periods as a precursor to the Gioco del Ponte, a grand public spectacle inaugurated in 1568 under the Medici. The Gioco del Mazza-scudo was abolished following the onset of Florentine rule in 1406.

A commemorative plaque, affixed in 1985 to the outer wall of the Oratory of San Rocco, reminds passers-by that in the medieval period the so-called Gioco del Mazza-scudo was regularly held the ‘Sette Vie’ area—later renamed Piazza dei Cavalieri—a practice common to many Italian communes. Local historians consider the event the most likely pre-modern precursor to Pisa’s festive tradition of the Gioco del Ponte, a historic contest between the city’s Mezzogiorno and Tramontana factions—each comprising six magistrature, or neighbourhoods—still proudly re-enacted each June on the Ponte di Mezzo.

Although they provide no detailed description, two later chronicle-style accounts—Raffaello Roncioni’s Istorie pisane(completed around 1605) and Jacopo Arrosti’s Croniche di Pisa (1654)—confirm that the custom was firmly established in the city by at least the mid-twelfth century. Roncioni’s earliest reference dates to the winter of 1168 (according to the Pisan calendar), although on that occasion the event took place not in the square, but on the frozen river Arno. Both authors, however, present it as a much older tradition, without offering further detail.

Arrosti adds that the arrival of the Florentines brought the game to an end, and that the Pisans were forced to hand over the maces used in the contest to the new governors — a detail that echoes a fifteenth-century Cronichetta on the city’s siege, published in the late nineteenth century alongside other anonymous texts.

Following the inauguration of the Gioco del Ponte in 1568, several literary works began to frame the Mazza-scudo as a kind of mediation between local customs of presumed Roman origin and the newly imposed Medici culture under Cosimo I. One such example is Giovanni Cervoni’s Descrizione delle pompe e feste fatte nella città di Pisa (Description of the Pageantry and Festivities Held in the City of Pisa, 1588–1589).

As for the nature and organisation of the event itself, our knowledge relies on a handful of earlier literary accounts—all of them, however, written after the competition had already vanished.

Puccino d’Antonio di Puccino da Pisa’s Lamento di Pisa (early fifteenth century, over 300 verses) and Giovanni di Iacopo di Talano da Pisa’s Lamento di Pisa (1452, 117 stanzas) both mention that the game took place in the ‘piazza’—most likely referring to the future Piazza dei Cavalieri—though without offering specific details. Far richer in information is an anonymous vernacular poem, Il Giocho del massa-schudo, composed in the early fifteenth century. Though the original poem is now considered lost, in 1882, dottor Stefano Monini, Prior of Bagni di San Giuliano and owner of the manuscript containing it, published the work in a wedding book, editing it at Tito Nistri’s typography.

Comprising forty-four stanzas of eight lines each, the poem confirms 1406 as the final year in which the festival was held in the city. It describes how, at least in its later years, the square was prepared: a central space between the surrounding buildings was enclosed by a ring of chains with two opposing openings, allowing participants to enter. The two principal factions of knights—known as the Gallo [Cock] and the Gazza [Magpie], distinguished by yellow and red helmets respectively—anticipate the structure of the later Gioco del Ponte. Each faction was further subdivided into groups known as compagnie or magistrature, each with its own banners and uniforms.

After the opening parade through the streets and the positioning of the participants, the tournament began with individual duels between men armed with a mace and a shield, each competing for the favour of a woman watching from the crowd. This was followed by a group clash between the two factions, signalled by the sound of a trumpet. The poem also records that the event took place annually between Christmas and Carnival. The buildings facing the square were lavishly decorated, their balconies and windows adorned and ready to receive spectators, while in the ‘palagio maggior’ (i.e. Palazzo degli Anziani), ‘i signuori cho’ cittadini de la terra i maggiori’ [the lords together with the town’s leading citizens] took their seats.

The presence of the Commune’s political figures observing from within the Palazzo degli Anziani gave the festival a distinctly public character—one later reinterpreted in grand-ducal form with the Gioco del Ponte. However, as recent scholarship has noted, there is no evidence of a direct link between the spectacle practised under Medici-Lorraine rule and its medieval precursor.

The scant historical record of the Gioco del Mazza-scudo suggests that the event—ideologically embraced by Pisan communal institutions and regularly staged in their immediate vicinity—ceased to exist following the city’s loss of autonomy in the early fifteenth century.

1406

Gino Capponi’s Speech After the Conquest of Pisa

On 9 October 1406, Gino Capponi entered Pisa with his troops and, meeting no resistance, immediately assumed control. This marked the beginning of Florence’s definitive conquest of the city and the establishment of a government that would remain in place, uninterrupted, for nearly a century—until 1494, two years after the death of Lorenzo the Magnificent.

This fresco, painted in 1585 by Bernardo Barbatelli—better known as Bernardino Poccetti—on the vault of the Great Hall in Palazzo Capponi, depicts Gino di Neri Capponi delivering a public speech in the summer of 1406. He is shown addressing assembled citizens and civic authorities gathered in Piazza del Popolo (later known as Piazza dei Cavalieri), speaking from the top of the external staircase of the Palazzo degli Anziani (later known as Palazzo della Carovana). Although no extant documentary evidence confirms the specific episode portrayed in Poccetti’s work—created nearly two centuries after the event—the fresco remains closely linked to the early fifteenth-century developments that culminated in Florence’s political and military conquest of Pisa, prior to the Medici era.

Gino Capponi (Florence, c. 1350–1421) was a prominent politician who played a leading role in the conquest of Pisa and became its first governor under Florentine rule. A member of a merchant family, he began holding public office in the late fourteenth century, having aligned himself with the Albizzi. In the spring of 1405, as Florence sought to incorporate Pisa into its external dominions, Capponi served on the magistratura dei Dieci della Guerra, the council of ten senior officials responsible for military policy and wartime decisions. He was sent to Genoa, Livorno, and Pietrasanta to negotiate—first with Jean Le Maingre Boucicault, who had governed Genoa for four years, and later with Gabriele Maria Visconti, Pisa’s lord since the death of his father, Gian Galeazzo, in 1402. After five months of diplomacy, as a peaceful resolution appeared within reach, the occupation of Pisa’s fortress on 31 August 1405 triggered an unexpected uprising, which Capponi quickly suppressed by leading the Florentine army to besiege the city.

Numerous fifteenth-century sources—produced by both the victors and the vanquished—document the events of 1406. Some of these accounts help reconstruct what occurred in Piazza del Popolo following Florence’s entry into the city and Pisa’s immediate surrender.

Among the Florentine sources, one of the earliest and most significant is Giovanni di Ser Piero’s Capitoli dell’acquisto che fe’ il Comune di Firenze, di Pisa, a poem in Dantesque terza rima composed in 1408 during his tenure as podestà of Castel Fiorentino. The poem recounts the gradual encirclement of Pisa by Gino Capponi’s troops, beginning in mid-May 1406 and culminating in an agreement with Giovanni Gambacorta, who had seized power during the city’s political vacuum and was granted governance of Bagno di Romagna in return.

On the evening of Saturday, 9 October 1406, the feast day of Saints Denis of France and Domninus, the Florentines entered Pisa through Porta San Marco without armed assault or looting, finding themselves before a population starved by months of siege. As Giovanni di Ser Piero’s verses recount, one of the first acts carried out by Gino Capponi and his men upon entering the city was having ‘preso del palagio signoria’, that is, the seizure of Palazzo degli Anziani, the quintessential symbol of Pisa’s now-collapsed communal civic power.

Decades later, Neri Capponi—likely the governor’s eldest son—composed the Commentari di Gino di Neri Capponi dell’acquisto, ovvero presa di Pisa seguita l’anno MCCCCVI, probably based on his father’s notes. The work was later translated into Latin by Bernardo Rucellai. These accounts report that, upon entering the Piazza del Popolo, the young Florentine Jacopo Gianfigliazzi was immediately knighted, while Chancellor Scolaio d’Andrea di Guccio was sent to the Palazzo degli Anziani to secure suitable lodgings for the captain and commissioners. A parade through Pisa’s main streets then followed.

Other Florentine sources include an anonymous vernacular chronicle, traditionally attributed to Piero di Giovanni Minerbetti, which covers the years 1385 to 1409 in an annalistic format; Bartolomeo di Michele del Corazza’s Diario fiorentino, composed as a series of brief entries between 1405 and 1439; and Giovanni di Pagolo Morelli’s Ricordi, compiled up to July 1421. While broadly consistent with one another, these accounts are more succinct than earlier sources such as Giovanni di Ser Piero’s poem and Neri Capponi’s Commentaries. Del Corazza’s Diario, in particular, concentrates on the celebratory atmosphere in Florence’s streets following news of the victory.

Matteo Palmieri’s treatise De captivitate Pisarum, written in 1445 by the Florentine humanist born in 1406, also deserves mention. Though not a contemporary witness, Palmieri reworked earlier sources—most notably Neri Capponi’s Commentaries, to which his treatise is dedicated. Significantly, he locates the events of 9 October in front of what he already refers to as the Priorum palatium [Palace of the Priori], the future Palazzo della Carovana, rather than the earlier residence of the Anziani—thus reflecting the Florentine magistracy occupying the building at the time of his writing. He also notes that the ‘insignia of the Florentine people’ [‘Florentini populi signa’] were affixed to the palace façade that same day.

Turning to the Pisan perspective, an anonymous Cronichetta and a set of equally anonymous Ricordi were transcribed by Giuseppe Odoardo Corazzini in his 1885 volume compiling unpublished sources on the siege of Pisa. The Cronichetta contributes little beyond what is already found in Florentine accounts such as Giovanni di Ser Piero’s poem and Neri Capponi’s Commentaries. The Ricordi, however, are of particular value: alongside Capponi’s Commentaries, they constitute the only known contemporary record to preserve Gino Capponi’s oration in the Piazza delle Sette Vie.

Matteo Palmieri’s De captivitate Pisarum includes a lengthy speech, reimagined in humanistic style as a reworking of the version found in Neri Capponi’s account. In its second book, Jacopo Arrosti’s Croniche di Pisa (1654) focuses exclusively on the events that took place in the Piazza and at the Palazzo degli Anziani on 9 October, the day of the Florentines’ entry into the city. Capponi, however, delivered his public address only the following day, 10 October, speaking to the Elders as they prepared to vacate their residence, and to the assembled Pisan citizens.

The orations preserved in the Commentari and Ricordi differ markedly in form, yet both adopt a tone that is at once triumphant and conciliatory towards a people newly deprived of the autonomy they had proudly upheld for centuries.

Media gallery

1565

Founding Ceremony of the Church of Santo Stefano

Following the established tradition for beginning major construction projects, the laying of the foundation stone of the Conventual Church of Santo Stefano dei Cavalieri was marked by an official ceremony attended by Duke Cosimo de' Medici, Cardinal and Metropolitan Archbishop of Pisa Angelo Niccolini, the local clergy, and a large group of knights clad in the order’s formal attire. Medals bearing Cosimo's likeness, struck in various metals, were cast into the building's foundations.

As part of Giorgio Vasari‘s unified design for Piazza dei Cavalieri, which followed the construction of Palazzo della Carovana, plans included a church—a necessity for a military order dedicated to defending Christianity. The building, dedicated to Saint Stephen (Pope, martyr, and namesake of the Order), was erected on a site combining the old church of San Sebastiano alle Fabbriche Maggiori and private plots of land. Its facade was perfectly aligned with the adjacent Vasarian palazzo. For roughly three years, while the crumbling walls of San Sebastiano were being demolished and new foundations excavated, the Order’s members – who had received papal approval from Pius IV in 1562 – held their services temporarily at the nearby church of San Sisto. This continued until construction of their new conventual building commenced in April 1565.

Scholars disagree on the exact dates of the church’s early construction phases, partly because historical sources used different calendar systems. Some documents followed the Pisan calendar, which began on 25 December and ran nine months ahead of the modern calendar, while others used the Florentine calendar, which ran nearly three months behind. According to Giovanni Capovilla, who discovered and analysed the relevant archival documents, construction began on 12 April 1565, when the Order’s Council granted its authorisation. However, marble slabs carved by Stoldo Lorenzi under architect Davide Fortini’s direction, bearing the date of 6 April 1565, were cast into the building’s foundations, suggesting that work likely began several days earlier. These slabs contained the following inscription:

Cosmus Medices Florentiē et Senarum Dux Inclytus | Fundata hac pietiss. A Nobilium equitum universitate | ad Reip. Christiane decus et incrementum, voluit eam esse | in fide et tutela Divi Stephani Pape et Martyris | Fanum hoc Divo eidem extruendum dedicandumque curavit | Lapidem primum, privumque, primus ipse iecit | Angelus Nicolinus Pontifex Pisanus et Cardinalis verba de more preivit | Actum anno a Servatoris ortu MDLXV | VI | Aprilis | Kyrianus Stroza Philosophie et Humanarum literarum professor, eiusdemque | Ducis in re literaria Administer Pisis

[Cosimo de’ Medici, illustrious Duke of Florence and Siena, having founded this most devout college of noble knights for the glory and advancement of the Christian republic, wished it to be in the faith and under the protection of Saint Stephen, Pope and Martyr. He had this temple built and dedicated to the same saint. The Duke laid the first stone, with the rite initiated by Cardinal Angelo Niccolini, ‘Pontiff of Pisa’, who spoke the words according to custom. Done in the year 1566 from the birth of our Saviour, on 6 April. Ciriaco Strozzi, Professor of Philosophy and Humanistic Letters and the Duke’s minister for literary matters in Pisa.]

A widespread custom adopted by Italian courts (and beyond) since the fifteenth century, the burial of commemorative slabs and medals in the foundations of new buildings left an indelible record for posterity. This practice was particularly cherished by the Medici family, as evidenced – to cite just two examples among many possible ones – by similar ceremonies involving the placement of medals bearing the likenesses of Cosimo and Francesco de’ Medici in the foundations during the construction of the fortresses ‘della Stella and del Falcone in Portoferraio’ on Elba Island and Terra del Sole in Castrocaro Terme (1565).

As for the laying of the foundation stone, in 1815, Giovanni Domenico Anguillesi incorrectly linked this event to Cosimo’s appointment as Grand Master of the Order on 15 March 1562 (1561 in the Florentine calendar), while it is now clear that the event must have taken place in April 1565. Capovilla believed he could identify the exact day as the seventeenth of the month, a date derived from an expense note presumably written after the fact. However, the reliable seventeenth-century account by Giuseppe Setaioli describes the solemn procession that took place on April 8, 1565 (1566 in the Pisan calendar) ‘at approximately eleven o’clock […] with the attendance of Cardinal Niccolini Archbishop and two bishops, the canons and all the clergy and the regulars, and about one hundred knights dressed in ceremonial attire, with the customary ceremonies’ [‘a hore 11 incirca […] con l’assistenza del cardinale Niccolini arcivescovo e due vescovi, li canonici e tutto il clero et li regolari e circa cento cavalieri vestiti d’abito con le solite cerimonie’].

The first slab of the conventual church, laid ‘under the corner in front of the church facing the palace’ [‘sotto il canto avanti la chiesa verso il palazzo’] by Duke Cosimo, who had come to Pisa specifically for the occasion, bore an impressed Medici coat of arms surmounted by the cross of Stephen ‘with some Latin letters and around its corners were some round hollows […] where the Duke, after the ceremony, placed several medals in gold, silver, and metal-bearing his image, and above these four copper plates covering said medals, and above another stone similar to the first, set with metals’ [‘con alcune lettere latine et attorno sui canti vi era alcuni incavi tondi […] dove il duca, fatta la cerimonia, pose più medaglie d’oro, d’argento, di metallo con la sua impronta e sopra quattro piastre di rame che coprivano dette medaglie e sopra un’altra pietra simile alla prima incastrata con metalli’ ]. It is not clear which Cosimian medals were used for Santo Stefano. Fifty bronze specimens, mentioned without further details in the Medici Guardaroba, were sent to Pisa for this purpose in 1565. According to a previously published reconstruction, these medals are most likely the pieces bearing the Duke’s effigy on the obverse and the Uffizi building on the reverse, which had already been struck by Domenico Poggini. However, it cannot be ruled out that these were likely medals created by the same artist according to a new, specific design. Indeed, two bronze specimens (inv. 6407; Dep. 2990) are still preserved today at the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, which bear not only Cosimo’s image on the obverse but, significantly, display on the reverse the inscription ‘RELIGIONIS ERGO’ alongside the Florentine lily—an emblematic choice that perfectly suited the occasion.

1585

The Tenshō Embassy in Pisa

During the spring of 1585, Francesco I de' Medici received in Pisa the visit of four young Japanese ambassadors who had departed from Nagasaki for Europe. The occasion allowed the Grand Duke to showcase the wealth of the Order of the Knights of Saint Stephen and the magnificence of its headquarters: the guests were taken on a tour of both Palazzo della Carovana and the church of Santo Stefano, where they had the opportunity to attend a sacred ceremony.

The expedition was conceived by the Jesuit Alessandro Valignano (1539-1606), who served as Visitor of the Indies. As the Society of Jesus’s representative in Asia, Valignano sought to showcase his order’s remarkable success in spreading Christianity throughout the region. Valignano carefully selected four young converts from Japan’s noble families for this mission to the Holy See and Pope Gregory XIII. Two represented Japan’s feudal lords: Itō Sukemasu, baptized as Mancio, and Chijiwa Seizaemon, baptized as Michele. The other two were nobles in their own right: Nakaura Jingorō and Hara Nakatsukasa, who took the Christian names Giuliano and Martino respectively. The expedition later became known as the ‘Tenshō Embassy’ (Tenshō shōnen shisetsu, meaning ‘mission of the youths in the Tenshō era’) and was the first Japanese embassy to reach Europe.

The exceptional significance of the event is documented in various contemporary printed pamphlets and chronicles, such as Guido Gualtieri’s Relazioni della venuta degli ambasciatori giapponesi a Roma sino alla partita di Lisbona (1586). The De missione Legatorum Iaponensium ad Romanam Curiam (1590) holds extraordinary documentary value as a fictional dialogue between the four young protagonists as they travel, likely written in Spanish by Valignano himself and translated into Latin by the Portuguese Jesuit Duarte de Sande. According to these and other contemporary sources, the embassy undertook an extraordinary journey: after crossing the Indian Ocean and circumnavigating Africa, they made their first European landfall at Lisbon. From there, they travelled to Madrid to visit the court of Philip II, then sailed from Alicante to reach the Italian peninsula, finally disembarking at the Tuscan port of Livorno. After visiting several cities in the grand ducal state, they proceeded to Rome, where Gregory XIII granted them a private audience on 23 March 1585. Although Valignano had planned their itinerary carefully, the Japanese princes had to agree to numerous deviations: one of these long diversions occurred at the Medici court in Pisa, where the embassy stayed for five days, from 2 to 7 March 1585.

Francesco I de’ Medici, who then resided in this city with Grand Duchess Bianca Cappello, thus had the privilege of being the first Italian ruler to welcome the travellers to his state. Having landed in Livorno on 1 March 1585, the young Japanese were received by his emissary, who invited them to reach Pisa the day after their landing in grand ducal carriages, where ‘they found a palace richly prepared for them’. Following this welcoming gesture, they were formally received by Francesco I, his brothers Pietro and Ferdinando, and the Grand Duchess, who invited the missionaries to stay in the family’s ancient Pisan residence, situated near the church of San Matteo (today the site of the Prefecture).

A sixteenth-century volume printed in Florence in 1585 recounts that on this occasion, Mancio, to satisfy the Grand Duke’s ‘ethnological’ curiosity, appeared before him dressed in traditional Japanese clothing, displaying ‘a pair of most delicate shoes of mottled-coloured leather, with knitted stockings of various colours, […] a pair of hanging trousers in Turkish style reaching to the ankle, woven of gold cloth and embroidery, with emeralds, pearls and rubies, […] a long sleeveless coat, embroidered to the waist with similar jewels, with most superb and rich workmanship.’ [‘un paro di scarpe dilicatissime di corame di color mascherezato, con calzetti agucchiati di varii colori, […] un paro di calzoni pendenti in foggia turchesca fino sul collo del piede, tessuti di drappo d’oro, e di ricamo, con smeraldi, perle e rubini, […] una casacca lunga senza maniche, fino alla cintura ricamata di simili gioie, con superbissimi e ricchissimi lavori’.] Thus, admirably attired, the noble Mancio – continues the anonymous chronicler – was reportedly ‘painted in portrait by Buontalenti’. This final anecdote appears in neither Gualtieri’s chronicle nor in the De missione. There is only mention of the Grand Duke and Duchess’ great admiration for the young men’s traditional garments.

During their stay in Pisa, which coincided with the transition from Carnival to Lent, the Japanese legates divided their time between social gatherings, religious ceremonies, and visits to the city’s monuments. On the very evening of their arrival, the group attended an event at Palazzo Medici, where Grand Duchess Bianca was hosting a sumptuous court ball; here, as recounted in a lively passage of the De missione, the young foreigners provoked general amusement among the noble attendees by demonstrating their inexperience with European dances.

The following day, according to the same source, they devoted themselves to visiting the ‘templum maximum miris sumptibus aedificatum’[‘the major temple (i.e., the Duomo of Pisa) built with great wealth’], and then the ‘conventum eorum, qui Divi Stephani equites appellantur’, or the [convent of those who are called Knights of Saint Stephen], most likely the Palazzo della Carovana. After a brief digression on the prestigious chivalric orders established by princes and kings across Europe, Michele— who is tasked with narrating the embassy’s Pisan sojourn in the fictional dialogue De missione, describes the visit to the headquarters of the Order of Saint Stephen, specifically the eponymous church and the conventual palace, and highlights the remarkable wealth possessed by this knightly institution. His account particularly emphasises the knightly institution’s great wealth. In this setting, Francesco I de’ Medici’s distinctive role as patron of a religious-military order clearly impressed the four travellers, who came to regard the Grand Duke as having authority equal to that of a king.

Inside the church of Santo Stefano, the four travellers had the opportunity to attend and participate in the Ash Wednesday liturgy: on the first day of Lent 1585, in the presence of eighty Stephanian knights and, naturally, their Grand Master (the Grand Duke himself), the young Japanese also received the imposition of ashes on their foreheads. Francesco I sat on a high seat near the main altar, and, facing him, the four guests were accommodated in an equally prominent position. Before the ritual began, the knights, arrayed in in their ceremonial robes, bowed before the foreigners, then knelt before the altar and gracefully paid their respects to the Grand Duke with the kissing of his hand. After the Mass, the travellers admired the church walls adorned with numerous battle standards – trophies captured from pirate ships by the Order’s galleys. According to De missione, the Order maintained a fleet of four swift, well-equipped vessels at this time.

Although it still was still lacking its façade in 1585, the church of Santo Stefano did not fail to garner the group’s keen admiration: the narrator describes its architectural structure as ‘as remarkable as that of the order’s headquarters’, referring to the nearby Palazzo della Carovana. This building constituted the final stop on the Pisan ‘tour’ offered by Francesco I to the young Japanese princes, who were shortly afterwards invited to continue on to Florence. Inside the palace, further confirming the triumphal enterprises conducted by the Knights of Saint Stephen, the group of ambassadors could contemplate the ‘many sacred relics, a most rich treasury, and a cabinet full of all manner of weapons’ [‘molte sacre reliquie, un ricchissimo tesoro, un armadio pieno di ogni specie di armi’].

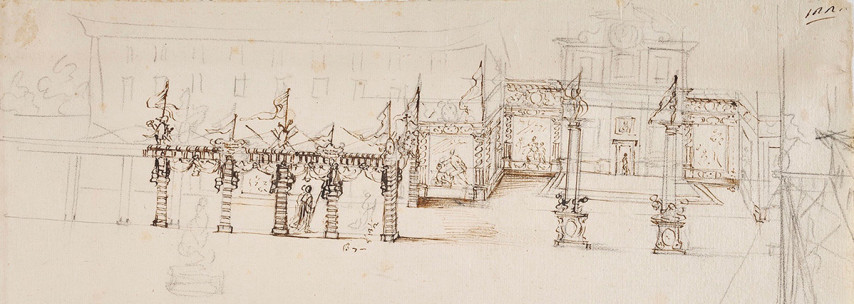

1588

Entry of Ferdinando I into Pisa

On 31 March 1588, Pisa erupted in celebration for the ceremonial entry of its new Grand Duke, Ferdinando I de' Medici. Cheering crowds and prominent local figures lined the streets as he processed through the city centre, where temporary decorations and monumental triumphal arches transformed the urban landscape. After the procession, Ferdinando and his retinue withdrew to Palazzo Medici along the Arno River. The following day, he visited the Knights of Santo Stefano, who welcomed their Grand Duke – and Grand Master – with a deferential ceremony in their conventual church, where they swore him unconditional obedience.

Having departed from Florence several days earlier and stopping at Villa dell’Ambrogiana, Cardinal Ferdinando I de’ Medici – who had become the new Grand Duke of Tuscany just months before – reached Pisa on the morning of 31 March 1588. Following tradition, he made his triumphal entry to ‘come to review and give orders to reform his noble city’ [‘venire a rivedere e a dar’ ordine di riformare la sua nobile città’]. Despite the city’s economic hardships at the time, Pisa’s community rallied to prepare for this prestigious arrival. They decorated every corner of the town and created sumptuous festive displays along the Grand Duke’s planned processional route through the centre. A precious and detailed account of the event is preserved in the description written by Giovanni Cervoni, a literary scholar and legal advisor to the Medici court. His meticulous documentation covers every aspect of the ceremony – from initial preparations through to the final execution – and provides detailed descriptions of all installations and decorative elements.

At Cascina, where Ferdinando was welcomed by the Pisan militia and high-ranking city officials, he alighted from his carriage, mounted a chinéa (ceremonial white horse), and continued his journey toward the city with a large entourage in attendance. The procession began at Porta San Marco, where a monumental triumphal arch had been erected to celebrate the Grand Duke’s good governance. Passing through throngs of cheering crowds along Via di San Martino, the procession reached the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, where the Florentine community in Pisa had erected a second arch extolling the sovereign’s moral virtues.

Next came the displays mounted by the Ufficio dei Fiumi e Fossi (Office of Rivers and Ditches), celebrating their successful land reclamation projects and those of the Customs Office. Ferdinando encountered more triumphal arches after crossing the Ponte Vecchio (known today as Ponte di Mezzo). At what is now Piazza Garibaldi stood the first, adorned with canvases illustrating scenes from his life and career. Further along the Arno riverbank, on the approach to Palazzo Medici (now Palazzo Reale), stood another arch commissioned by the Studio Pisano, celebrating the Grand Duke’s intellectual achievements. The procession continued beneath an arch where musicians performed from a special platform – ‘under the arch and platform arranged for the Music […], which was performed during his passage’ [‘sotto l’arco e palco ordinato per la Musica […], la qual si fece nel suo passare’] . At the naval arsenal, the final arch was crowned with allegorical statues of Justice and Peace.

After spending the night at the family palace, the next day the Grand Duke wished to pay homage to the Knights of the Order of Saint Stephen, of which he was the Grand Master. They received him with solemn celebrations in a festively decorated Piazza dei Cavalieri. Ottavio Piazza and Ridolfo Sirigatti coordinated and supervised the implementation of the festive arrangements. Escorted beneath a canopy, Ferdinando was led to the entrance of the Church of Santo Stefano, whose facade – then incomplete and therefore lacking the marble cladding still visible today – had been covered for the occasion with wooden scaffolding designed to support temporary structures used to make its appearance more majestic. A grand portal with an architrave was erected before the building’s entrance, its fluted pilasters adorned with festoons and inscriptions. Painted canvases were set between these, depicting allegorical figures of Beatitude, Victory, Active and Contemplative Life, Fidelity, and Obedience alongside the Grand Duke’s heraldic insignia. The church interior, as bare and undecorated as the facade, had been entirely covered with festoons, fabric hangings, flags, and a cycle of five grisaille canvases (still in situ) depicting Episodes from the Life of Pope Stephen I, Martyr, following an iconographic program once again designed by Sirigatti and executed by a group of more and less well-known painters, including Alessandro Pieroni dell’Impruneta, Jan van der Straet, known as Stradanus, and Giovanni Balducci, known as il Cosci. Ferdinando was received by the Prior of the Order, who offered him holy water and then led him to the high altar, where the knights, who had all gathered in the church for the occasion, paid him homage offering their obedience, while musicians intoned the Te Deum in the background.

Media gallery

1609

The Reception of the Bona Victors by Grand Duke Cosimo II in Pisa

Perched on the Algerian coast, the city of Bona (modern-day Annaba) served as a strategic Turkish stronghold, whose forces had become particularly notorious for their brutal torture of Christian soldiers, captured after a shipwreck shortly before the Order of Saint Stephen launched its mission. On 16 September 1607, not without difficulty, the Medicean army succeeded in conquering the enemy fortress. In April 1609, the victory - among the most important ever achieved by the Order - was finally celebrated in Pisa with a solemn ceremony in Piazza dei Cavalieri. The young Grand Duke Cosimo II, who had recently succeeded his father Ferdinando I, played a central role in the celebrations.

The capture of the city of Bona (modern-day Annaba, on the northeastern coast of Algeria) was the outcome of a major military operation conducted on land and sea and by the Knights of Saint Stephen in service to the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinando I de’ Medici. Admiral Iacopo Inghirami commanded the mission alongside Silvio Piccolomini, Grand Constable of the Stephanian Order and tutor to the young Grand Prince Cosimo II, in whose name the expedition was launched. The motivation for the plan likely stemmed from a recent pirate attack against several ships of the Order that had been wrecked off the Maghreb coast. The soldiers from these vessels were taken prisoner and subjected to horrific torture, culminating in the display of their severed heads atop the walls of Bona. As one of the most strategically significant Ottoman strongholds in the Mediterranean, Bona’s capture would offer Ferdinando’s government not only vengeance but also increased prestige and enhanced regional influence. Beyond these strategic advantages, the victory carried symbolic importance as a response to Ottoman aggression, particularly following the Turkish siege and capture of Famagusta in Cyprus during the summer of 1607.

223 x 301 mm

The Stephanian fleet consisted of nine galleys, three galleons and two bertons (three-masted ships), accompanied by smaller vessels and an army of over two thousand men, including knights and mercenary soldiers. The mission was planned and programmed down to the smallest detail. Still, several unexpected events during the approach to the coast caused a dangerous delay and threatened to jeopardise the entire outcome. Nevertheless, on 16 September 1607, Piccolomini decided to proceed with the landing and, despite the difficulty of the enterprise, managed to lead his troops to victory. After the battle, Bona was sacked and torched while the army immediately prepared to depart for Livorno.

As paradigms of the Ecclesia triumphans, victories over the Turks were celebrated by the Order with great pomp, following strictly codified ceremonial procedures. The Bona enterprise was thus celebrated in Pisa on 1 April 1609, with a procession in Piazza dei Cavalieri and a solemn mass in the church of Santo Stefano. According to contemporary chronicles and documents, for this momentous event, Grand Duke Cosimo II – who had recently succeeded his deceased father – arrived in the city on 26 March with his wife Maria Maddalena of Austria, several days ahead of the celebration.

On 1 April, dressed in his robes as Grand Master of the Order, Cosimo received the processional cortege in the church. The procession was led by the Knights of Tau – formerly the ancient Order of San Giacomo of Altopascio, which had been absorbed by the Stephanian Order in the late sixteenth century – accompanied by trumpet players. Following them came Grand Constable Piccolomini bearing the standard of Religion, thirteen prisoners in ceremonial dress carrying insignia, and finally, the other knights. Kneeling before the altar, the Grand Duke gathered in prayer, after which the Turkish banners captured at Bona were presented to the officiating monsignor, who blessed them, formally sanctioning their definitive consignment to the Order. The meticulous planning of the event, of which written record is preserved in the Archivio di Stato di Pisa, added that after the celebrations, ‘His Most Serene Highness will retire to the sacristy to remove his robes, and at the same time all the lord knights will remove their robes. His Most Serene Highness will then return to hear low mass’ [‘Sua Altezza Serenissima si ritirerà in sagrestia a spogliarsi l’abito, et nel istesso tempo tutti i signori cavalieri si caveranno l’abito. Sua Altezza Serenissima poi tornerà a sentir messa piana’]

In 1613, the Knights commissioned one of the painted panels on the ceiling of the church of Santo Stefano to commemorate the Battle of Bona. Bernardino Poccetti and his assistants had already depicted this theme in a cycle of paintings on the piano nobile of Palazzo Pitti in Florence (1607-1609). The 1609 celebrations were later depicted in a fresco by Baldassarre Franceschini (known as il Volterrano) as part of a larger decorative scheme commemorating Medici triumphs in the external loggia of Villa della Petraia, a Medicicean country house located near Florence (1636-1646). Finally, in 1694, the success of the Stephanian fleets became the subject of a heroic-encomiastic poem dedicated to Cosimo III de’ Medici by Count Vincenzo Piazza, a Knight of the Order, titled Bona espugnata (Bona Conquered)

Media gallery

1683

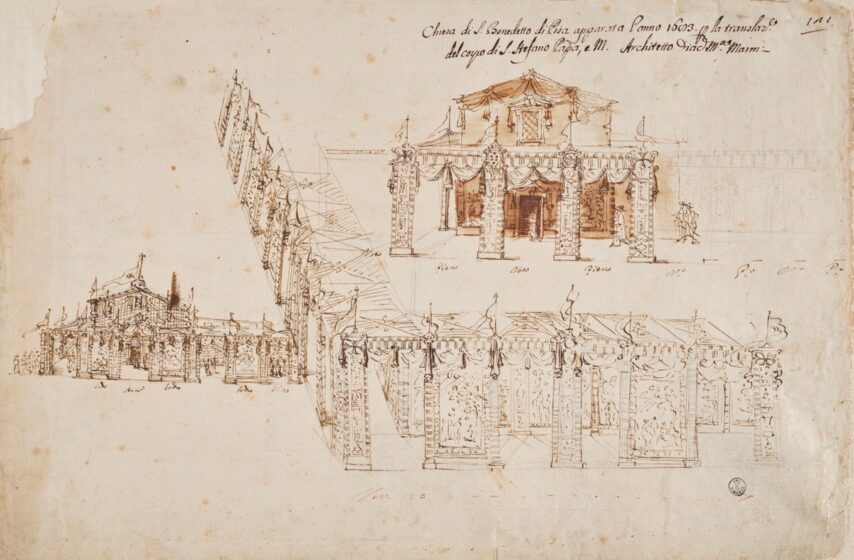

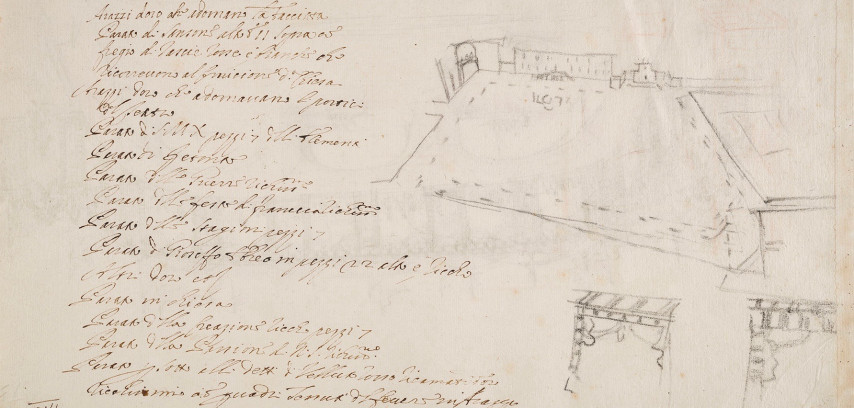

Translation of the Relics of Saint Stephen

On 25 April 1683, Pisa hosted the solemn ceremonial transfer of the relics of Saint Stephen, pope and martyr, from the church of San Benedetto to Santo Stefano dei Cavalieri. The event was orchestrated by the grand-ducal guardarobiere Diacinto Maria Marmi, who designed its sumptuous ephemeral decorations, and was attended by many members of the Medici family in Piazza dei Cavalieri. The ceremony culminated in Santo Stefano, where Giovan Battista Foggini had created a gigantic wood-and-stucco model for the occasion, showing the Saint between Religion and Faith - a work still preserved in the church today.

The Order of the Knights of Saint Stephen had coveted the saint’s remains since 1571, when Giorgio Vasari was tasked with securing their acquisition. The relics, however, once preserved in various locations within Rome, had already been dispersed further afield. In 1611, small fragments of the body and some vials of the saint’s blood were discovered in the monastery of the Observant Friars of Santa Maria della Colonna in Trani, which Grand Duke Ferdinando II de’ Medici unsuccessfully attempted to obtain.

The relics were finally granted to the Order in 1682, during the reign of Cosimo III de’ Medici. This came after lengthy negotiations with the authorities of Trani – where the saint was already established as protector- and a papal brief from Pope Innocent XI. After their arrival – by land to Naples and then by sea – the sacred remains were initially preserved in the lower church of San Benedetto, under the Knights’ jurisdiction. The Knights organised the transfer ceremony for the following year’s Divine Mercy Sunday, 25 April 1683, to coincide with the Order’s General Chapter meeting, during which positions would be renewed for three years.

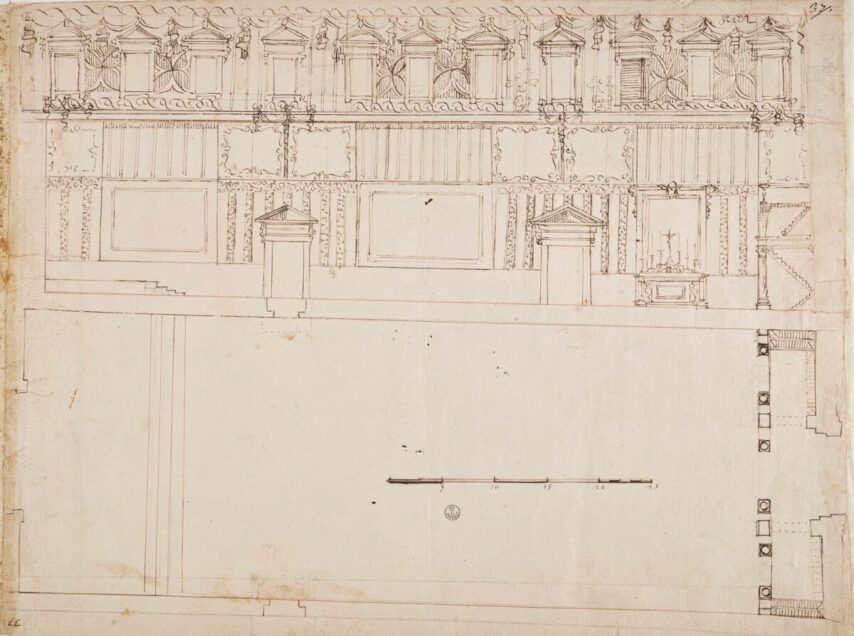

The ceremony, which culminated in Piazza dei Cavalieri, and the rich decorations adorning the route between the two churches are documented in several sources, both manuscript and printed. The event is also recorded in a letter by Diacinto (or Giacinto) Maria Marmi, the grand-ducal guardarobiere (wardrobe keeper) who designed the temporary decorations for the event. The lavish ceremony can be reconstructed through payments to numerous artists and craftsmen preserved in the Archivio di Stato in Pisa, a substantial group of drawings found in Florence, Pisa, and New York, and an engraving depicting the piazza’s decorations. Some of these drawings were intended to produce an illustrated printed account, which has not been found and may indeed never have been published. Nine views of the celebration were commissioned from Domenico Tempesti and Bastiano Tromba for the planned publication.

Six drawings by Marmi have been identified in the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe degli Uffizi, interpreted as sketches made after the ceremony and then provided to the two artists. The three drawings in the Archivio di Stato in Pisa appear to belong to an earlier, more operational phase during the development of the actual installation, and, in my opinion, their attribution to Marmi remains uncertain. Although Tempesti and Tromba completed the drawings for print – confirmed by a payment of 40 scudi – only one of the nine views has been found: the interior of Santo Stefano, now at the Morgan Library in New York.

During the celebration, meticulously reconstructed by Barbara Riederer-Grohs and particularly by Franco Paliaga, the reliquary was removed from the lower church of San Benedetto and displayed among candles and silverwork on the altar of the upper church, which had been decorated for the occasion with tapestries depicting sacred scenes. San Benedetto’s facade was adorned with pillared scaffolding draped in white and turquoise checkered cotton cloth. Above this rose an enriched frieze and cornice decorated with flags. A tapestry depicting the deeds of Cosimo I de’ Medici (not readily identifiable in the Uffizi drawing) hung between the allegories of Piety and Justice.

The reliquary was placed under a canopy and carried in procession by the Grand Duke, Cosimo III, dressed in his grand master’s robes and accompanied by a retinue of four hundred knights and clergy. The procession moved along the Lungarno to the Ponte di Mezzo, another highlight of the route. Here, the passage was marked by mortar fire and sumptuous decorations. The bridge was framed by two triumphal arches and covered with naval awnings, friezes, and coloured drapes. Tapestries depicting Faith, Hope, Joy, and Sorrow were placed at each end of the bridge, while additional tapestries with allegorical figures were installed between the pillars.

Along the Via del Borgo, a series of tapestries were displayed showing the Storie dei Medici (depicting Cosimo the Elder, Lorenzo the Magnificent, Clement VII, and Cosimo I), the so-called Parato della Vigilanza (Vigilance Tapestry), the cycle of ‘Florentine festivals,’ and other series dedicated to mythological figures.

Another triumphal arch, on which a chiaroscuro episode from the Life of Saint Stephen had been placed, led into the piazza, which was entirely surrounded by a wooden arcaded loggia supporting various series of tapestries: among these were the Stories of Saint Joseph, The Stories of Phaethon, the ‘Elements’ series, the Marriage of Henry IV and Maria de’ Medici, and individual pieces depicting sacred stories. In the piazza, waiting for the procession, were various members of the Medici family: Grand Duchess Vittoria della Rovere, the Princesses Ferdinando and Gian Gastone, and Cardinal Francesco Maria, the Grand Duke’s brother.

Once the procession had disbanded, the procession entered the church. In front of the church stood two columns, each crowned with an allegorical figure: Religion, bearing a standard emblazoned with the Knights’ coat of arms and with enemy spoils at her feet, and Victory, holding both a standard and a crown, similarly displaying captured enemy trophies at her base. Chained to the column pedestals were four captive figures, while the church facade was dominated by Grand Duke Cosimo III’s portrait, a work by Pietro Dandini created in collaboration with gilders and weavers.

The church interior had been fitted with a musicians’ gallery, thrones for the Grand Duke and Prior Felice Marchetti, and ‘gabinetti’ [loges] to accommodate the guests and court: among these, besides the Order’s authorities, were the Archbishop of Pisa Francesco Pannocchieschi d’Elci, and Monsignor Giacomo De Angelis, the Vicar General of the Diocese of Rome. The church was adorned with various tapestry cycles: the Grotesque series, the Life of Samson, and the Creation of Adam. From the ceiling hung a standard depicting the saint with an angel and, at its base, the kneeling figure of Religion. On the high altar, designed for the occasion by Pier Francesco Silvani, stood the plaster and wood figures created by Giovan Battista Foggini, depicting Saint Stephen between Religion and Faith, now preserved in a chamber to the right of the presbytery.

This was an event without precedent. Diacinto Maria Marmi resided in Pisa for forty-three days, directing a veritable team in a transformation that touched every aspect of the celebration. The extensive preparations ranged from comprehensive work on the church interior – including gilding, cleaning, and the complex movement of materials – to the meticulous preparation of every street along the processional route. Improvement works were carried out on the facades and roofs of the buildings. The streets were covered with sand, and the piazza was cleaned and paved with cobblestones in some areas.

Franco Paliaga emphasises the distinctive nature of the ceremony, which proceeded from one site under the Order’s jurisdiction to another – marked respectively by the portraits of Cosimo I and Cosimo III – traversing the city’s most important thoroughfares (the Lungarni and Borgo) via a system of covered galleries.

Marmi’s ephemeral decorations served both economic and symbolic purposes: many tapestries came from the Medici Guardaroba (wardrobe); curtains and other textiles were borrowed from Santa Maria Novella and numerous Florentine, Pisan, and Livornese institutions; other objects came from private loans. The vast sacred and secular repertoire inspired wonder and admiration, primarily emphasising decorative aspects, although some tapestries demonstrated the connection between the Medici dynasty and the Order, stressing the necessity of fighting against invasion at a particular historical moment: the Turkish advance at the gates of Vienna.

Media gallery

1765

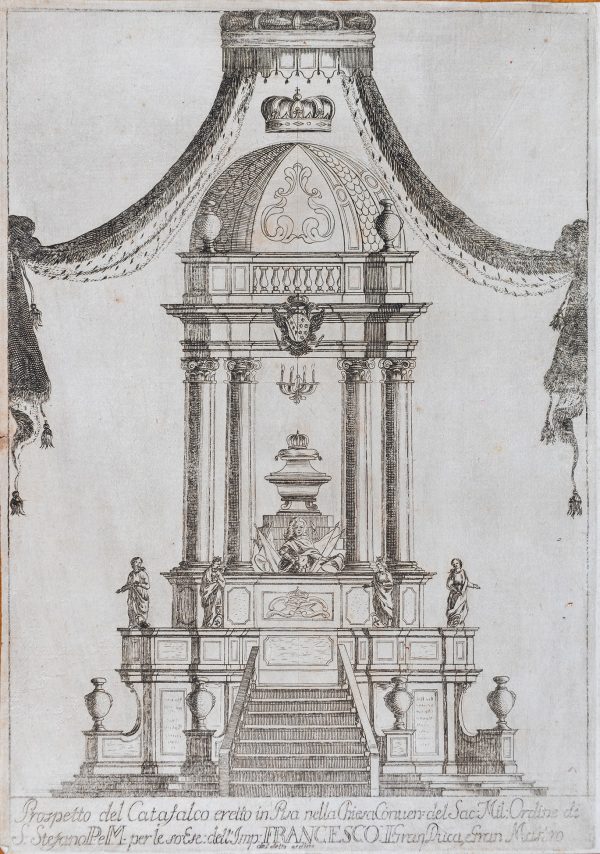

Funeral ceremonies for Francis I of Lorraine