Organs

On either side of the high altar of Santo Stefano dei Cavalieri stand two monumental pipe organs—one dating from the sixteenth century, the other from the first half of the eighteenth—both distinguished by significant construction histories.

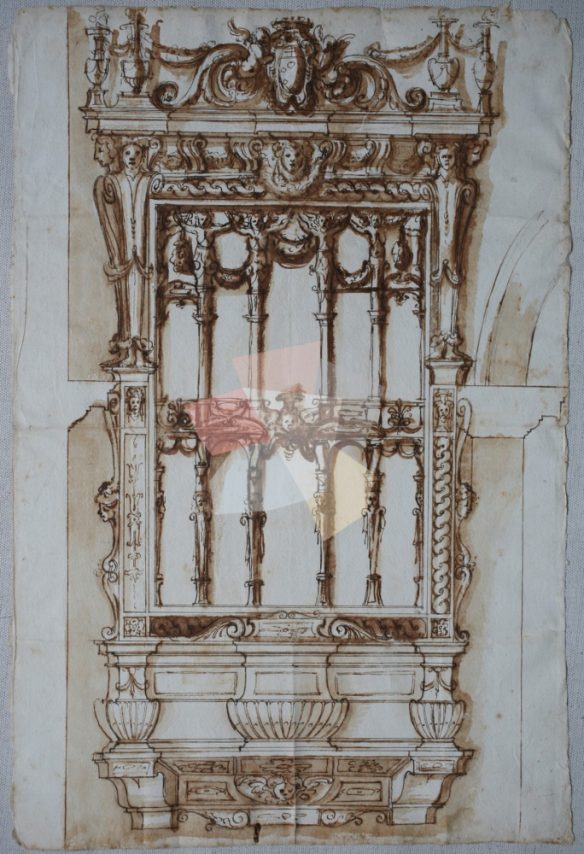

The construction of the older of the two organs began in the summer of 1569, when the Council of the Order, in agreement with the soon-to-be Grand Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici, resolved to furnish the convent church—then still largely bare—with an organ that combined refined aesthetics with the highest technical precision. The work was hurriedly entrusted to Onofrio Zeffirini of Cortona, with delivery required by Christmas of that same year. A natural choice for the task, Zeffirini belonged to one of the most prolific and respected organ-building families of the sixteenth century, particularly active in Tuscany. Zeffirini was to work from a design supplied by Giorgio Vasari, who served as both designer and sole supervisor of the works in Pisa. The drawing is still held in the State Archives of Pisa, while a second, more refined study of the instrument’s left section is preserved in manuscript Ottoboniano Latino 3110 of the Vatican Apostolic Library.

Besides Zeffirini—who accepted a fee of ‘200 scudi at 7 lire per scudo … on condition that 100 scudi be paid upfront, and the remainder upon completion’ [scudi 200 di lire 7 per scudo … con conditione se li faccia lo sborso di presente di scudi 100, et el resto a l’ultimo]—Giovanni Fancelli, called Nanni di Stocco, and Davide Fortini were also engaged to construct the ‘balustrades in marble and mixed materials’ [poggioli di marmo e misto] for the organ and the musicians. Nigi della Neghittosa, again working from a design by Giorgio Vasari, was responsible for the gilded wooden frame surrounding the instrument. The cost of this element—considered Zeffirini’s masterpiece and the most majestic organ he ever built—was entirely borne by Cosimo I, who also secured exemption from customs duties for the transport of its components, crafted in Florence and shipped to Pisa by river. Despite Vasari’s efforts to monitor progress closely, providing regular updates to the representatives of the Order of Saint Stephen, the project overran the scheduled timeline: Nigi delivered the gilded ornamentation in spring 1570; the balustrades were ready only by December; and Zeffirini completed the instrumental components in April 1571.

On 14 August 1571, the organ—at last completed—was installed in the church of Santo Stefano, on the left-hand side, facing away from the entrance (or more precisely, in cornu evangelii (on the Gospel side), where it remained until 1734. It was then moved to the opposite side, on the right (in cornu epistolae (on the Epistle side), to make room for a new monumental organ. This followed the earlier addition, in 1618, of a smaller instrument by Cosimo Ravani of Lucca—for which Ciro Ferri later proposed ornamental designs—and was conceived and donated to the Order by the knight Azzolino Bernardino della Ciaia. The new organ was enclosed in a carved and gilded wooden frame by the woodworker Andrea Andrei. Exceptionally innovative for the Italian context, it featured four keyboards and a fifth for the psaltery, in the manner of the great northern European organs, especially those found in France and Flanders. Its tonal structure, however, remained broadly aligned with the Italian tradition, though it included several unusual stops—such as the nazardone and cornettone—more typically associated with transalpine organ building.

Inaugurated in the autumn of 1737 during the tributes held in Santo Stefano for the late Grand Duke and Grand Master Gian Gastone de’ Medici, Azzolino’s organ—still unfinished at the time of its first use—was described the following year by its creator, once completed, in a printed pamphlet that remains an invaluable resource for reconstructing its original configuration. Like its sixteenth-century counterpart, the instrument underwent profound alterations through renovations and interventions.

Both Pisan organs—especially the eighteenth-century one—underwent modern interventions that significantly altered their structure and, consequently, their function. In 1896, there is documented evidence of an attempt to place one of the two organs—presumably the older, which had been dismantled following a fire and temporarily stored in the rooms of Palazzo della Canonica—under museum care.

Between 1907 and 1908, a first restoration plan was drawn up for the eighteenth-century organ, which had fallen into such disrepair that ‘the organist refused to make use of it [l’organista si è rifiutato di farne uso]. The project, prepared by consultants Filippo Tronci, Enrico Barsanti, and Giuseppe Menichetti, was ultimately rejected by the appointed supervisor, Giovanni Tebaldini, organist of the Holy House of Loreto. In light of the ‘such a prominent place in the history of musical art’ [posto sì alto nella storia dell’arte musicale] held by the Pisan instrument, Tebaldini instead recommended launching a competition for restoration specialists. This was eventually won by Giovanni Tamburini of Crema, who, after depositing a security bond to cover any potential issues or unforeseen consequences, undertook the organ’s periodic testing, tuning, and maintenance throughout the 1910s and 1920s.

In 1924, the electric motor was replaced and ‘the current converted from direct to alternating’ [la corrente da continua in alternata]. In 1930, the organ was electrically coupled with the sixteenth-century instrument, described in the relevant documents as ‘completely unusable’ [completamente inservibile]. This intervention inevitably compromised the original tonal configuration of both organs, which from that point onwards could be played using ‘a single three-manual console, located in the church’s choir’ [una sola consolle a tre tastiere, posta nel coro della chiesa].

In the post-war period, the organs—’which are the pride of the Pisans’ [che sono l’orgoglio dei pisani]—required further alterations to address damage caused by bombing in the summer of 1944, which led to the ‘collapse of part of the bell tower’ [crollo di una parte del campanile] and the subsequent fall of ‘dust and fragments of plaster’ [polvere e pezzi d’intonaco]. The older instrument suffered the most, with its components sustaining multiple fractures.

Between 1946 and 1951, various intervention plans were considered, but a lack of funds delayed the start of the work, which finally began in 1952. Additional minor operations were recorded during the 1960s, and from that point onward, routine maintenance was carried out periodically, with records attesting to its continuation into recent times.

Media gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.