Ceiling

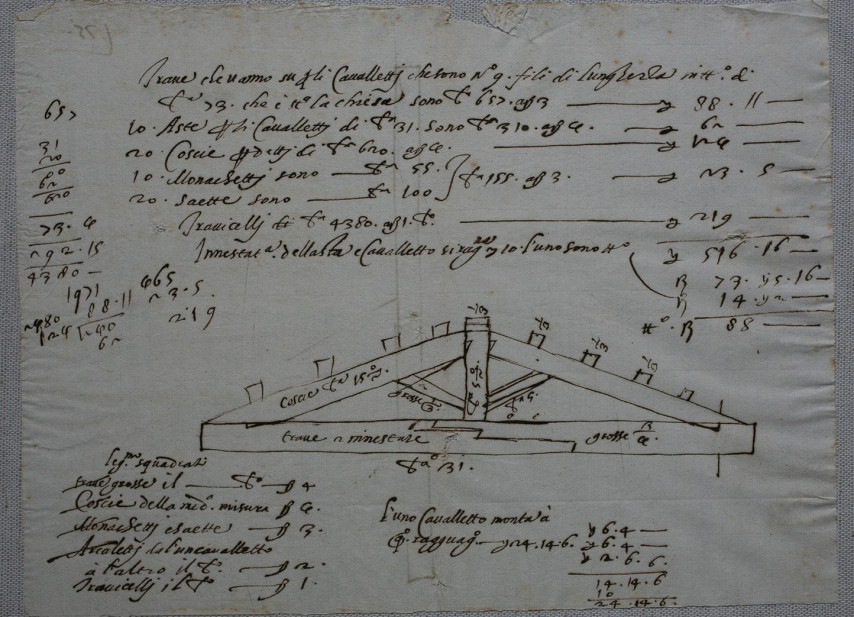

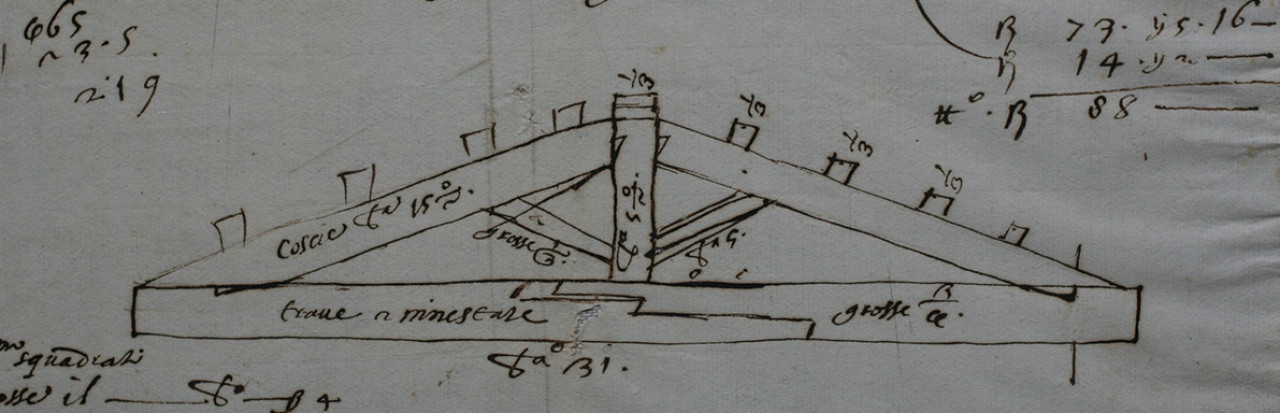

Construction of the Church of Santo Stefano began in the spring of 1566 and progressed rapidly until its consecration on 21 December 1569. Given the Order’s operational demands, a space for worship and ceremony was needed without delay, and the church was delivered in an unfinished state—with the bell tower still under construction and both the façade and interior completely bare. The spacious nave was roofed by a wooden structure consisting of ten trusses, designed—like most components of the church—by Giorgio Vasari. A drawing preserved in the Archivio di Stato di Pisa shows how the architect, who had recently conceived the monumental wooden ceiling of the Salone dei Cinquecento in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio, provided comprehensive technical instructions for its execution, including a detailed construction plan and even the length of the beams (31 braccia), testifying to his solid engineering acumen.

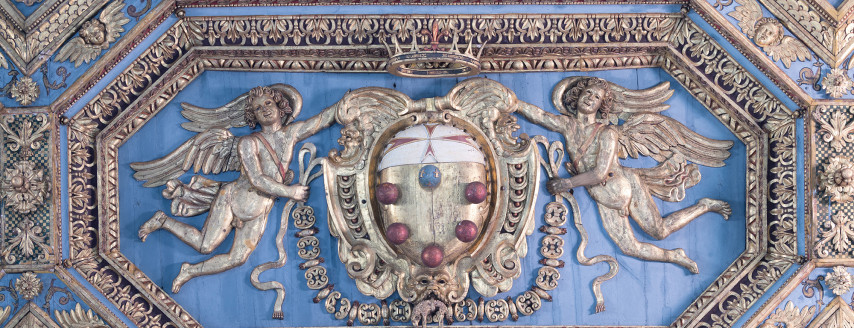

It was not until 1603–1604, long after Vasari’s death, that the ceiling was completed by Alessandro Pieroni, with Filippo Paladini responsible for the gilded carvings on a blue background that remain visible today. Conceived to address the deteriorating condition of Vasari’s original trusses, the refined ceiling is geometrically structured with rectangular, hexagonal, and octagonal coffers. Along the outermost cornice run octagonal coffers with rosettes, followed by shields bearing the emblems of the first Medici grand dukes—Cosimo I, Francesco I and Ferdinando I de’ Medici—together with an inscription recording its completion in 1604 under Ferdinando I’s patronage. Rectangular panels depicting panoplies and navigational instruments allude to the Order’s role as a maritime military power. In the central section, coats of arms featuring the eight-pointed cross of the Stephanian Order alternate with Medici insignia, all supported by flying angels. These are interspersed with six paintings depicting the naval exploits of the grand ducal fleet, each flanked by oblong hexagons bearing capitalised inscriptions that briefly describe the scene.

As documented by a valuable sequence of eleven drawings preserved in the codex Ottoboniano Latino 3110 at the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, which illustrate the various phases of the design process, planning for the Santo Stefano ceiling likely began around 1595. At that time, the church’s prior, concerned about the deteriorating condition of the roof, was presumably inspired by the new ceiling then under construction in the Pisan Cathedral by Bartolomeo Atticciati and Alessandro Pieroni, following a devastating fire that had destroyed its earlier covering. He resolved to commission a similar project for Santo Stefano. It was therefore no coincidence that Pieroni received the commission, and that his initial conceptual drawings show close affinities with the Cathedral ceiling, characterised by a pattern of square coffered panels. These forms gradually evolved into more elaborate compositions in later stages, incorporating allegorical and painted elements.

The initial proposals failed to satisfy the Order’s Council, which in October 1602 requested drawings from Rome—now also preserved in the aforementioned Vatican codex—depicting the city’s most distinguished ceilings to serve as inspiration for the Pisan project. Particular reference was made to the ceiling of Santa Maria in Vallicella, built under the patronage of then Cardinal Ferdinando de’ Medici. Ultimately, however, it was the ceiling of the Ara Coeli, dating to 1572 and commemorating the Christian victory at Lepanto, that had the most significant impact—both symbolic and practical—on the subsequent evolution of the design.

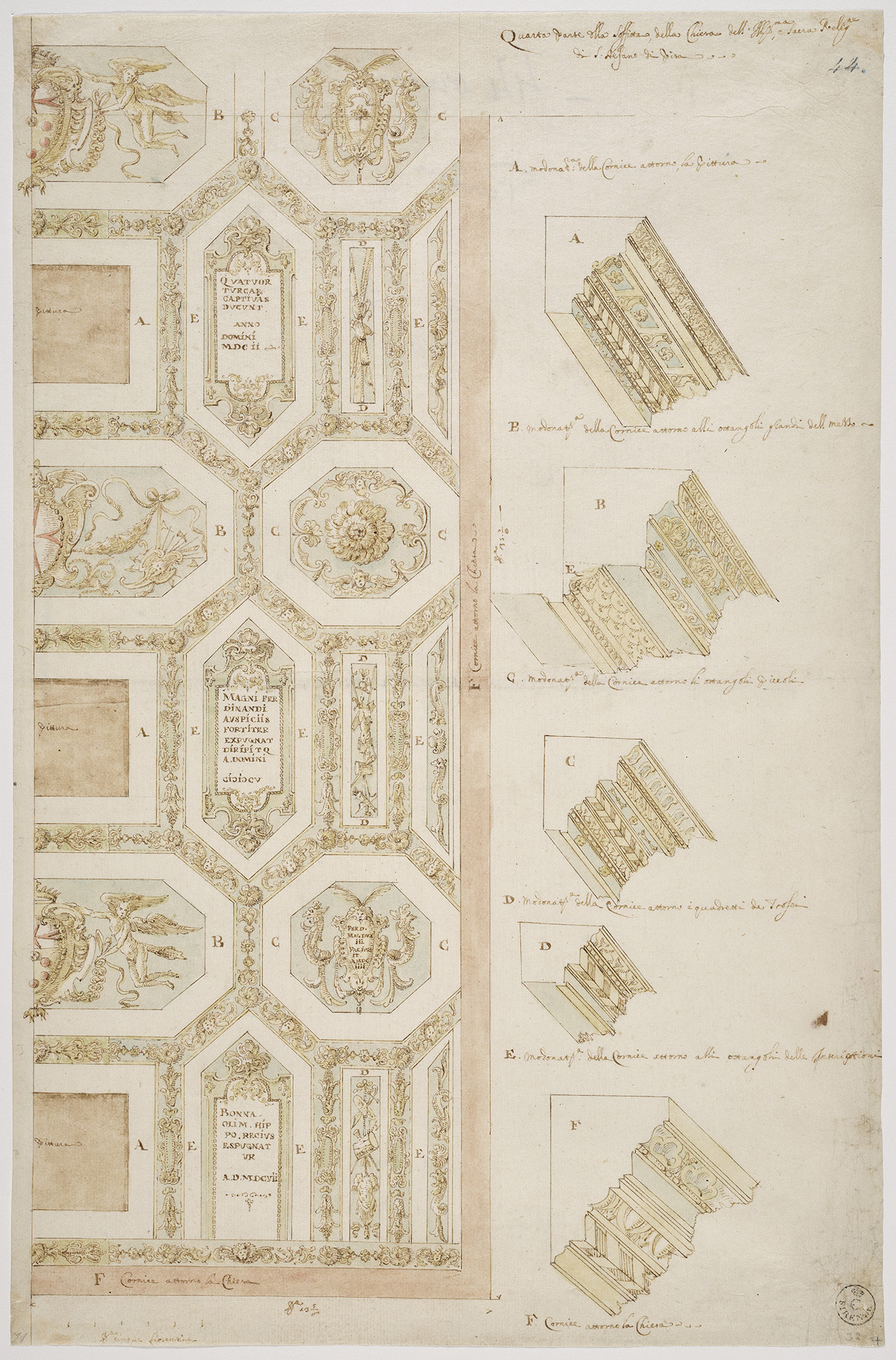

Structurally completed by 1604, the Pisan ceiling was fully decorated by 1614 through the gradual addition of painted panels depicting Stories of the Order of Saint Stephen—by which time Cosimo II had acceded to the throne. An anonymous drawing preserved at the Uffizi (inv. 44 Orn) offers an overview of the project, depicting the ‘Fourth part of the ceiling of the Church of the Most Illustrious and Sacred Order of Saint Stephen of Pisa’ [Quarta parte della soffitta della Chiesa dell’Ill.ma e Sacra Relig.ne di Santo Stefano di Pisa], accompanied by several three-dimensional sectional profiles of the ornamental frames. Its impact on visitors is confirmed by an early eighteenth-century note from De Rogissart, who remarked in his travel journal, ‘the vault is all gilded’ [la voûte en est toute dorée].

Pen and wash on white paper, 400 x 260 mm

Inscription: upper right: ‘Quarta parte della soffitta della Chiesa dell’Ill.ma e sacra Religione di S. Stefano di Pisa’

Inscriptions below the portioned section: ‘A. modanatura della cornice attorno, la pittura’ / ‘B. modanatura della cornice attorno alli ottangoli grandi dell [sic] mezzo’ / ‘C. modanatura della cornice attorno li ottangoli piccoli’ / ‘D. modanatura della cornice attorno li ottangoli delle interieptioni’ / ‘F. cornice intorno la chiesa’.

Inscription: lower left: ‘B[racci]a cinque fiorentine’;.

In 1616, shortly after the completion of the works, Paolo Guidotti—known as il Cavalier Borghese—submitted a proposal to the Order’s Council for the expansion of the church of Santo Stefano. Commissioned at the request of the grand duke and his wife, Grand Duchess Maria Maddalena of Austria, the project envisaged an extension of Pieroni’s ceiling—never carried out—designed to cover the new areas that would have converted the church’s single-nave layout into a Latin cross plan.

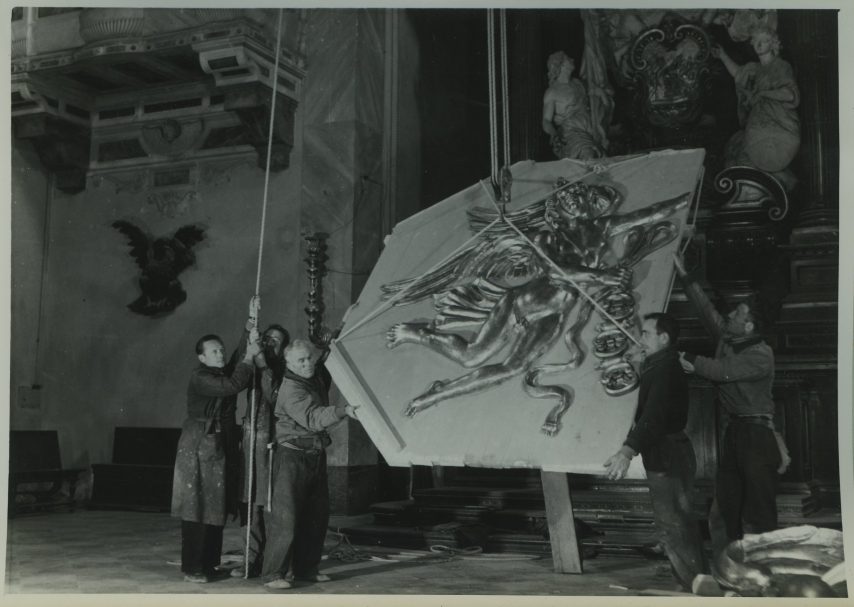

The fragile ceiling—directly anchored to Vasari’s trusses—presented persistent structural challenges, which required repeated interventions, particularly after the Second World War bombings that also damaged the church’s bell tower. In 1944, the roof was declared unsafe, and in 1945, a major conservation campaign was launched. This involved dismantling the ceiling section above the high altar to repair the trusses beneath, which had been compromised by the collapse of the bell tower and were held in place by temporary supports. Several fallen wooden fragments were retrieved, including the heads of some shield-bearing angels. Additional structural damage was recorded in 1947 and 1948; however, due to the lack of funds, only provisional shoring was installed until 1949, when iron tie-rods were finally added.

The large wooden ceiling remained structurally unstable for decades, prompting a series of emergency repairs. Beginning in the 1950s—particularly in 1954–55, when loose sections were removed, reattached, or remade from scratch—interventions continued sporadically into the 1990s, ending with a complete dismantling and consolidation of the entire structure in 1995. More recently, a new restoration project has been initiated by the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio for the provinces of Pisa and Livorno.

Media gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.