Urban Development, 16th-19th Centuries

In 1562, under Cosimo de’ Medici and the direction of Giorgio Vasari, the former Piazza del Popolo was transformed into a striking Mannerist urban setting, designed to house the principal buildings of the Order of Saint Stephen, among them its conventual church, from which the area initially took its modern name, ‘Piazza Santo Stefano’, still recorded by Ernst Moritz Arndt at the end of the eighteenth century. By that time, however, ‘Piazza de’ Cavalieri,’ already in common use since the seventeenth century, had become widespread and was became its sole and official name in the nineteenth century.

Except for San Sebastiano alle Fabbriche maggiori, which was demolished to make way for the Order’s church, Vasari reused the existing medieval structures of the piazza for his new buildings. In addition to the surviving material evidence, Vasari himself notes this in a passage of the Vite (1568), where he explains how he adapted Palazzo della Carovana onto ‘part of the old’ Palazzo degli Anziani ‘as best he could, on those old walls, bringing them up to the modern’ [‘una parte del vecchio’… ‘come ha potuto il meglio, sopra quella muraglia vecchia, riducendola alla moderna’]. Recent excavations at Palazzo della Canonica have confirmed the methods by which Vasari and his team repurposed earlier structures.

The choice, later repeated by other architects working on the piazza, was primarily dictated by economic reasons: it reduced the costs and time of demolition while simultaneously providing a ready supply of building materials on site. This procedure was further supported by measures introduced by Cosimo, which prohibited the reuse of masonry from demolished Pisan buildings outside the city boundaries and, at certain times, even abolished the duties on transporting construction materials within the walls.

There were also structural reasons. On unstable soil such as that of Pisa ‘once the first solid layer of the foundation was broken, the walls always sank’ [rotto il primo piano sodo del fondamento, le muraglie calavano sempre], relying on buildings that had long stood offered greater assurance of success, as Vasari observed in his Vite, in the biography of Nicola Pisano, where he considered Pisano to be the architect of the Palazzo degli Anziani. In particular, he credited him with having restored in the city the good practice of laying foundations ‘on pillars, and upon these turning arches, having first driven piles beneath the said pillars’ [sui pilastri, e sopra quelli voltare archi avendo prima palificato sotto I detti pilastri]. According to some construction notes from 1564, ‘palafitte di legnami’ (timber piles) were found (although not in good condition) ‘in the foundations’ [ne’ fondamenti] of the medieval structures later incorporated into the Palazzo della Carovana.

However, as is shown by the contemporary situation in Florence, other reasons were also symbolic. According to Vasari’s Ragionamenti (1588), during the renovation of the Palazzo Vecchio, carried out at the explicit request of the duke, the artist from Arezzo left the building’s ‘mura maternali’ (its original medieval fabric) untouched. Even after his interventions (from the late 1550s through the 1560s), the palace retained its fourteenth-century appearance on the piazza. The rationale was that these walls, ‘’in their old form, gave rise to his new government’ (‘con questa forma vecchia dato origine al suo governo nuovo’) : a political continuity that Cosimo wished to make visible to his fellow citizens by preserving the exterior of the historic seat of the Florentine magistracies.

In Pisa, by contrast, a complete transformation was undertaken. This was necessary to replace the dwellings of the former communal authority with those of the new ducal (and soon grand-ducal) government, embodied in the city by the military-religious Order of St Stephen. In Vasari’s plans, no element of the medieval past of the Palazzo della Carovana—built in the very years of the Palazzo Vecchio renovation—was intended to remain visible. Our current view of Piazza dei Cavalieri as a strikingly layered palimpsest is the result of a series of early twentieth-century interventions designed to bring to light traces of Pisa’s communal past from beneath the Medicean overlay. These included the opening of a pseudo-Gothic quadrifora in the Palazzo dell’Orologio and the enhancement of pre-modern remains revealed during work on the lateral walls of the Carovana itself. Such initiatives, often promoted by local authorities, were carried out not without accusations of ‘disturbing the sixteenth-century harmony of the piazza’.

The initiatives undertaken by Cosimo in the eastern sector did not immediately alter the urban layout. By the time of the grand duke’s death in 1574, the prestigious headquarters of the Knights had been completed, yet it stood in an area still visually marked by medieval structures such as the Tower of Famine, the Palazzo del Capitano del Popolo, and the Palazzo dei Priori (which in the fourteenth century had housed the Camera del Comune and was later transformed into the Palazzo dei Dodici). This coexistence characterised the piazza for more than two decades, and was clearly observed at the close of the century by travellers such as Robert Dallington and Giovanni Botero. They admired the ‘splendid palazzo[della Carovana]’, commissioned by Cosimo, while remaining attentive to pre-modern landmarks such as the ruined Tower of Famine. During this period, only the small oratory of San Rocco was subject to works, with the advancement of its façade into the piazza.

Under Ferdinando I de’ Medici, between the final years of the sixteenth and the early seventeenth century, Pisa’s urban fabric was rapidly standardised within fifteen years. This period saw the completion of structures begun by Vasari, including the façade of Santo Stefano and that of Palazzo della Canonica, as well as the near-contemporaneous modernisation of the Palazzo dei Dodici, which was still occupied by the Priori at the time.

With the construction of the Palazzotto del Buonomo (now Palazzo dell’Orologio) in the early seventeenth century, the last medieval vestiges of the piazza were effectively erased. While it remains uncertain to what extent these works followed Vasari’s original vision (by 1569, he had certainly drawn up a plan, if only for the Palazzotto), the progression of the project clearly aimed to transform the area into a closed enclave for the Knights. This intent is evident in the intervention promoted by the Order itself on the western side, where the only open space, Piazza delle Sette Vie, lay roughly between the former church of San Pietro in Cortevecchia and the fourteenth-century Camera del Comune. Here, in the latter half of the 1590s, three terraced houses were constructed to complete the theatre, employing an economical building type already in use in Florence.

The incorporation of San Rocco into this structure in the early 1610s, after the grand duke’s death, brought the architectural space to a definitive equilibrium. The ‘varied perspectival convergences’ [varie convergenze prospettiche] of the streets leading into it helped to regularise the irregular alignments of the façades of its principal buildings, and its ‘focal point of maximum visibility’ [centro espositivo di massima visibilità] was defined by the statue of Cosimo I. Commissioned by Ferdinando in honour of his father while work on the piazza was still underway, the monument also celebrated Ferdinando’s initiative to bring to Pisa the new Medicean aqueduct.

Following these decisive early works, the topographical configuration of Piazza dei Cavalieri remained virtually unchanged, except for the addition between 1683 and 1688 of two lateral wings to the sixteenth-century single-nave structure of Santo Stefano dei Cavalieri. The intervention was part of the renewed interest Cosimo III took in the Order. In September 1690 the Grand Duke formally donated the square to the Knights, for which he was also trying (in vain) to obtain autonomous ecclesiastical jurisdiction from Pope Alexander VIII. Excluded from its raised churchyard—set three steps above ground level—and left with exposed masonry, these the added wings were seen by early visitors, among them Luc-Jean-Joseph van der Vynckt in 1724, as leaving the sacred building apparently incomplete. Set back from the façade, perhaps to preserve the prominent view of the piazza for those approaching from the Cathedral, they were later ‘completed’ and ‘monumentalised’ between 1933 and 1935. The result was a disharmonious impact on the area. In the second half of the eighteenth century, there was even talk of furnishing the area with another monumental statue, this time dedicated to Francis of Lorraine, who had succeeded the last Medici – Gian Gastone – in the government of the Grand Duchy, but the proposal was ultimately not accepted by his son, Leopold.

As confirmed by the plan by Giovanni Domenico Rinaldi (1725) and that by Giuliano Giuseppe Ricci (1732), in the eighteenth century the square was unpaved except for two carriage paths made of cobblestone (one connecting the current Via dei Mille and Via Ulisse Dini, the other from Via San Frediano to intercept the former in the centre) and for the sidewalks in front of the buildings, created at the beginning of the seventeenth century using Golfolina stone. The area in front of Palazzo della Carovana, for example, was raised by a step to include the statue of Cosimo I and the adjoining fountain, both surrounded by a railway to protect the monumental group. In the early nineteenth century the cobblestones were replaced by sandstone paving and a layer of gravel was distributed on the unpaved road.

Before the turn of the century, oil lanterns had been installed for lighting. One, documented from at least the final years of the eighteenth century and still clearly visible in a celebrated view by Adèle Poussielgue (1838), stood at the corner of the Palazzo della Carovana and today’s Via dei Consoli del Mare. Another lit the entrance to the piazza from what is now Via Corsica. In the second half of the nineteenth century, oil was replaced by gas, marking the beginning of the twentieth century of modernisation. This period once again accelerated the transformations of the piazza, in a dialogue not always easy between historical awareness, symbolic and political values, preservation, and the daily needs of citizens.

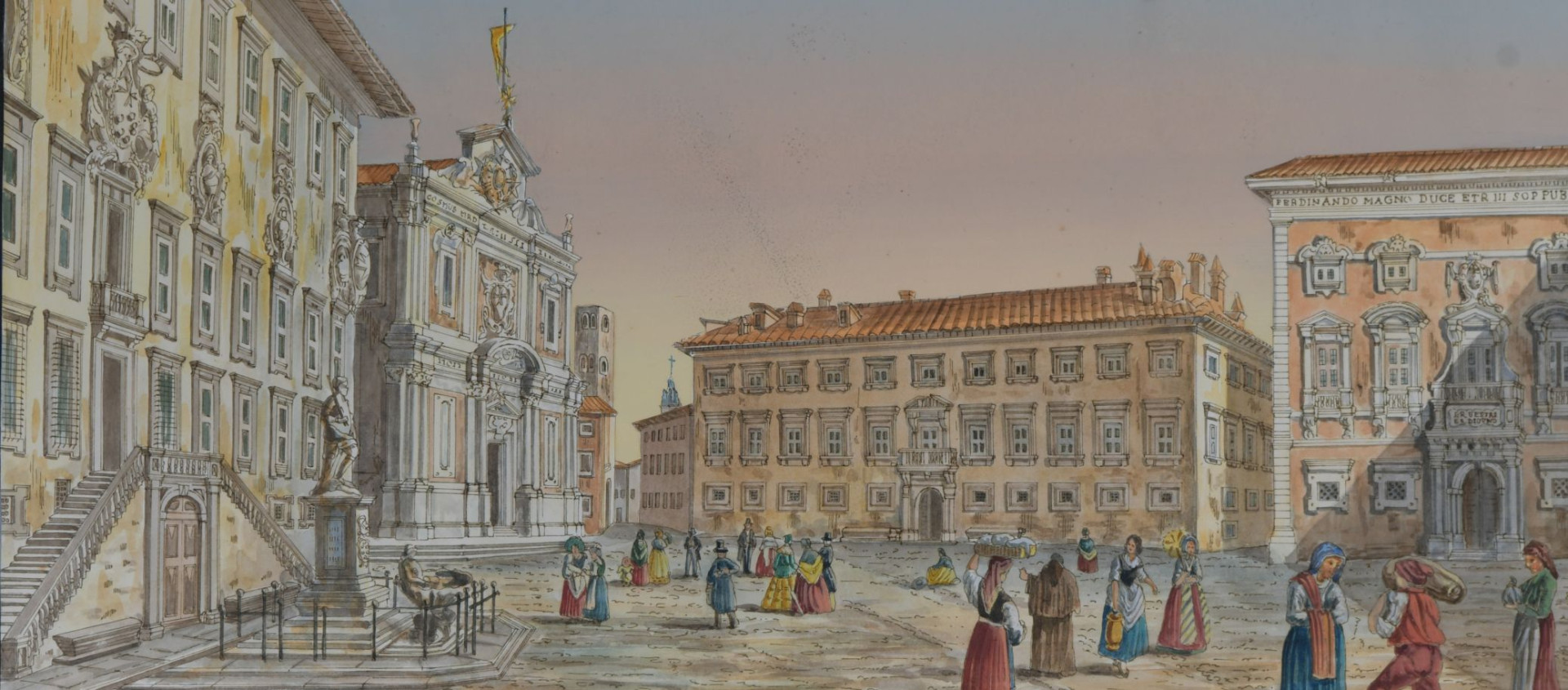

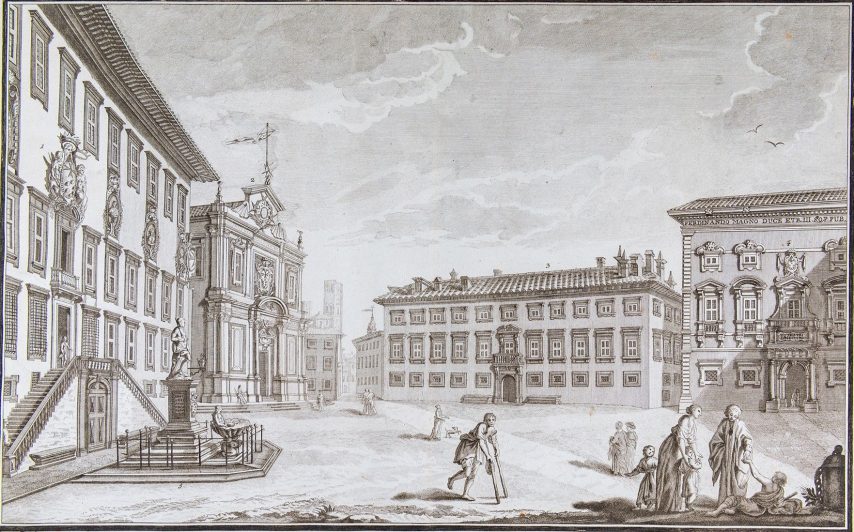

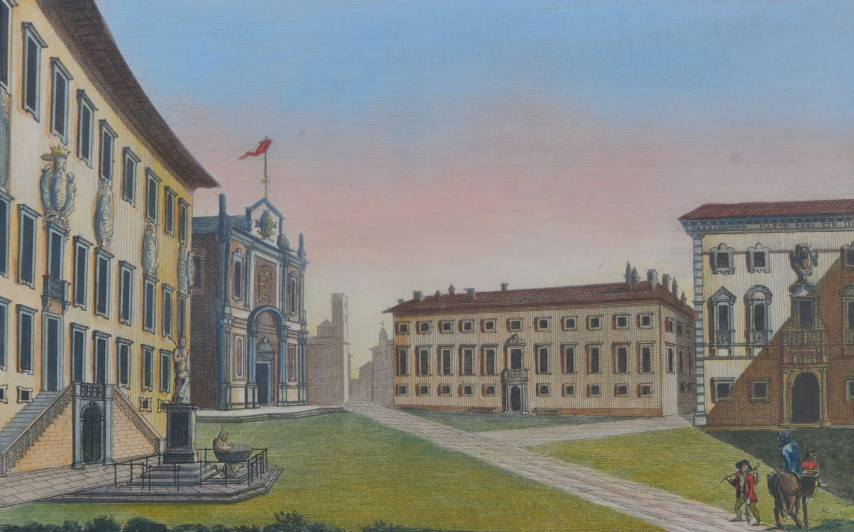

Etching and engraving

Coloured etching, 140 x 200 mm

Aquatint, 152 x 220 mm

Aquatint, 152 x 220 mm

Media gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.