Functions

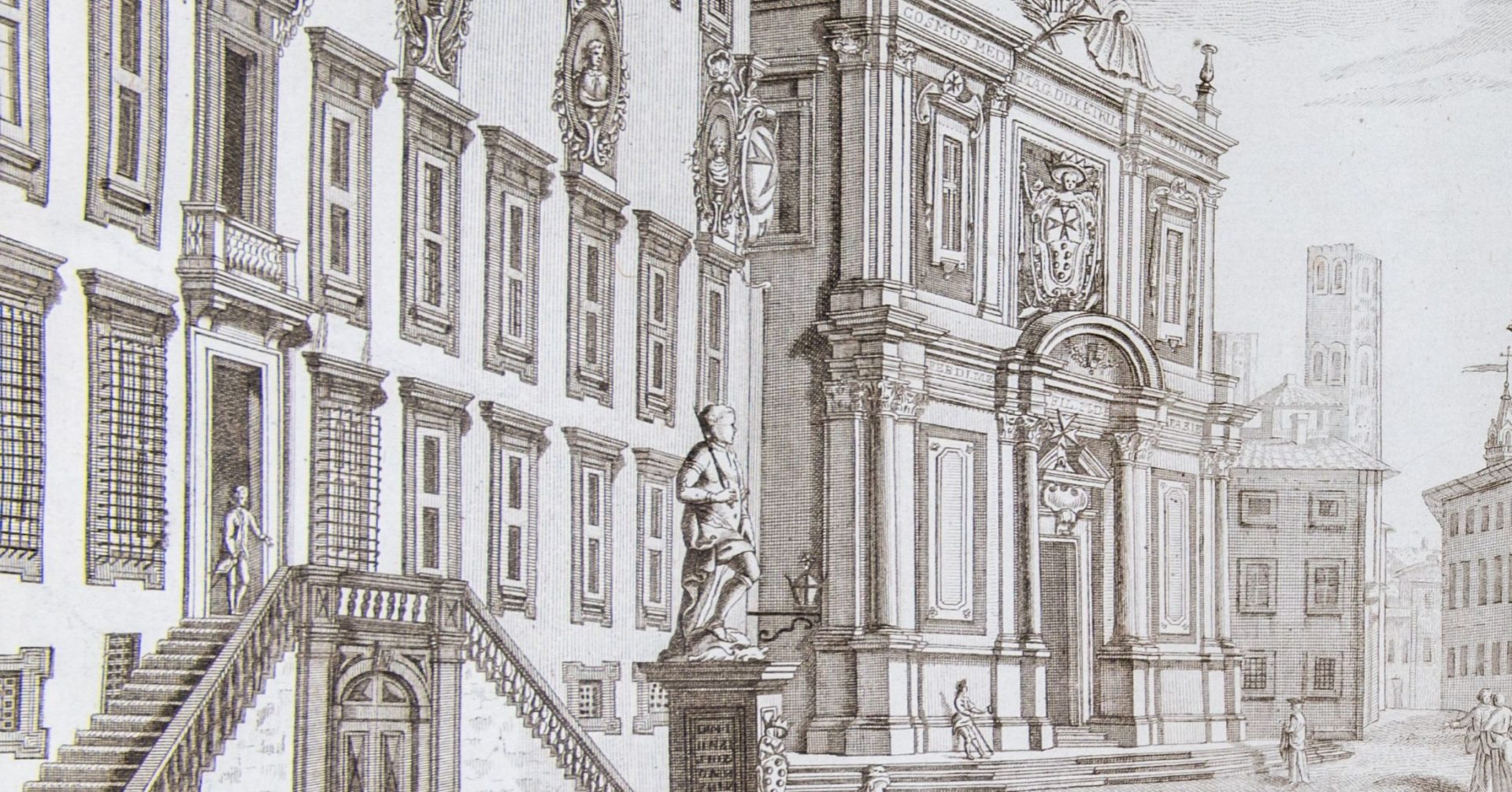

On 3 November 1564, Giorgio Vasari, architect of Palazzo della Carovana, then nearing completion, wrote to the Stephanian knight Leonardo Marinozzi, who was overseeing the works in his absence. He asked that Tommaso di Battista del Verrocchio, who was in Pisa to execute the sgraffito decoration of the façade, be accommodated ‘in a room either in the palazzo itself or nearby, because this greatly facilitates the completion of the work’ [‘stanza o costì in palazzo o vicino, perché inporta all’opera assai al finilla’]. While it cannot be ruled out that artists and craftsmen were among the earliest occupants of the medieval building renovated at the behest of Cosimo de’ Medici, later evidence confirms that the palazzo initially served as an operational base for the duke’s interventions in Piazza dei Cavalieri. The ground-floor hall (the future Sala della Colonna), intended to serve as the armoury of the Order of Saint Stephen, was still being used in 1568 as a timber store and a workshop of a carpenter. It is also likely that Ridolfo Sirigatti carved the marble bust of Cosimo for the façade within the palazzo itself, where both the block of marble intended for the work and its terracotta model had meanwhile been brought. It is certain, however, that in the second half of the sixteenth century, the wooden models designed by Vasari for the church of Santo Stefano and for the conventual palazzo itself were kept in the Carovana.

Alongside these specific uses—which we may assume gradually diminished and eventually disappeared—the building’s principal function for two and a half centuries, from the 1560s to the first decade of the nineteenth century, was to house the knights of the Order of Saint Stephen and its leading dignitaries. In other words, the palazzo served as a residential convent. Only for about a century—until the acquisition of the adjacent Palazzo dei Dodici—did it also accommodate the Order’s principal governing bodies, housed in the rooms now known as the Sale della Direzione. Exceptionally, every three years, on the occasion of the Order’s General Chapter, the building also hosted the investiture of the grand master. This ceremony took place on the morning on which the assembly convened, when the knights, clad in ‘their regular habit’ [‘loro abito regolare’], awaited the arrival of the grand duke within their ‘convent’ [‘convento’], as recorded in 1701 by the Jesuit Fulvio Fontana. We also know that two small suites on the second floor of the palazzo, fitted with new, purpose-made furnishings, were occupied—at least in 1775—by the Offices of the Secretaries of State and Finance during the stays in Pisa of Grand Duke Leopold I.

Despite Fulvio Fontana’s praise of the ‘statue nobili’ and ‘pitture’ that adorned Palazzo della Carovana (together with Palazzo della Canonica) in the early eighteenth century, relatively little is known about its interior decoration and furnishings during its period of use by the Order. One work securely documented: Aurelio Lomi’s Holy Family with Pope-Saint Stephen, now displayed in Santo Stefano dei Cavalieri, which had been commissioned for the Council Room, that is, the present-day Sala del Gran Priore (within the Sale della Direzione). The only furnishings mentioned by several eighteenth-century guidebooks are the rich collection—now partly still in situ—of Stephanian coats of arms. This collection originally also included the Cosimo marble coat of arms, now in Palazzo dei Dodici and attributable to Stoldo Lorenzi. In 1751, Pandolfo Titi recorded that these ‘arms’ [‘arme’] were kept ‘in a great hall’ [‘in un gran salone’], that is, the future Sala Azzurra. Writing in 1773, Gioacchino Cambiagi observed that the coats of arms were displayed not only in the ‘hall’ [‘salone’] but also ‘in other parts of the palazzo’ [‘in altri luoghi del palazzo’]. Some twenty years later, Da Morrona confirmed that they covered ‘all the internal walls’ [‘coperte tutte le muraglie interne’] of the building, adding that there was nothing else ‘worthy of remark, because in buildings intended for communal residence one rarely seeks luxury, but almost always comfort and utility’ [‘di rimarchevole, perché in fabbriche destinate all’abitazione di comunità, raramente si cerca il lusso, ma quasi sempre il comodo e l’utile’]. Whatever their extent, the furnishings housed in Palazzo della Carovana were sold following the Napoleonic suppression of the Order in 1809, in order to make the building available to French troops and, during the stays of Elisa Bonaparte in Pisa, to accommodate her pages.

Owing to the impossibility of carrying out the extensive renovations required to convert it into a court of assizes within a short time, the building was designated in January 1811 as the seat of the criminal court. It assumed its present role as the seat of the Scuola Normale Superiore only in 1846, some thirty years after the restoration of the Order in 1817. A few years later, however, a project to enlarge the service areas overlooking the Carovana’s internal courtyard indicates that a ‘bell-ringer’ [‘campanaio’] resided within the palazzo complex, and that provision was still being made for accommodation for several chaplains, almost certainly attached to the nearby church of Santo Stefano. Moreover, at least until 1867, galley fragments acquired by the Order some twenty years earlier remained on display in what is now the Sala Azzurra; only in that year were they transferred to the adjoining church, by which time the institution had already been suppressed eight years earlier by the provisional government of Bettino Ricasoli. By contrast, the painting depicting Leopold II now displayed on the internal grand staircase probably belongs to the original nineteenth-century Lorraine furnishings of the palazzo. It was rediscovered in the early twentieth century in an ‘attic’ [‘soffitta’] of the building, where it may have been placed when the last grand duke left Tuscany in 1859. The following year, Tuscany’s annexation to the Kingdom of Sardinia (and later to Italy) was ratified by a plebiscite, one of whose polling stations was located in Palazzo della Carovana itself.

Several paintings by Tuscan Mannerist artists that still adorn the Sala degli Stemmi today date from Giovanni Gentile’s refurbishment of the building, rather than from its original furnishings. These sixteenth-century works were probably removed during the war, as suggested by the inscription ‘Protezione Antiaerea 1944’ found on the reverse of some canvases. The palazzo went through particularly dramatic moments, especially after the armistice of 8 September 1943 and the subsequent Nazi occupation. In the turbulent months that followed, the mathematician Leonida Tonelli succeeded in ‘restraining the petulance and intrusiveness of the Germans, who wished to requisition the School for their military needs’ [‘tenere a freno la petulanza e l’invadenza dei tedeschi, che avrebbero voluto requisire la Scuola per i loro bisogni militari’], ensuring that ‘life at the Normale’ [‘la vita normalistica’] could continue, ‘albeit within a very reduced family’ [‘sia pure in sparutissima famiglia’]. These events were recalled three years later by Luigi Russo, then director of the Normale, who also left a vivid account of the ‘magnificent Palazzo della Carovana… occupied by Anglo-American forces… for twelve very long months’ [‘magnifico Palazzo della Carovana… occupato da milizie angloamericane… per 12 lunghissimi mesi’]. There, he wrote, ‘the chimneys smoked for the Allies’ radiators and their blazing stoves’ [‘fumavano i comignoli per i termosifoni degli alleati e le accesissime stufe’], while ‘the windows were enlivened by the acrobatics of young American air force officers in the cheerful company of their women’ [‘le finestre erano allietate dalle acrobazie dei giovani ufficiali dell’aviazione americana nella compagnia lieta delle loro donne’]. Temporarily housed in Palazzo del Puteano, the normalisti—students and professors alike—could hear ‘the loud music of nocturnal dances’ [‘le musiche alte delle danze notturne’] and see the ‘lavishly illuminated windows’ [‘finestre sfarzosamente illuminate’]. Disaster was narrowly averted when a stove nearly triggered a fire that threatened the entire building, which remained under requisition until September 1945.

These were exceptional events. From the mid-nineteenth century, Palazzo della Carovana hosted—almost without interruption—the studies and daily life of the normalisti until at least the 1980s. By that time, the building no longer housed the students’ refectory, which had been transferred to the adjacent Palazzo d’Ancona, inaugurated in 1971. It was therefore assigned exclusively to the institution’s administration and to its teaching and representative activities, definitively losing its original—and hitherto uninterrupted—character as a male residential college. Available evidence suggests that even after women were readmitted to the Normale in 1952, female students were never accommodated in the Carovana. Excluded in the 1930s by Giovanni Gentile, who opposed the admission of non-resident students, upon their readmission, the normaliste were instead housed in the Collegio Timpano, initially a women-only college overlooking the Lungarno.

Palazzo della Carovana

Main Entry- Preesistenze medievali

- Fasi costruttive

- Functions

- Façade

- Interior

- Varisco, Quadri comunicanti – Jarred

- Aula Bianchi

- La collezione dei calchi epigrafici

- Le opere del Centro Pecci

- Sala della Mensa

- The Coats of Arms of the Knights

- Sala Azzurra

- Sala del Ballatoio

- Sale della Direzione

- Scalone

- Gastini, «… e finire è cominciare»

- Maruscelli (attr.), Figura virile

- Sala degli Stemmi

- Sala della Colonna

- Cortile

Media gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.