Florentine and Medicean Magistracies

[15th-18th centuries]

The loss of Pisan independence, although sanctioned without bloodshed in the autumn of 1406, brought about the end of citizens’ effective participation in political life. Florentine rule was exercised directly from the outset, and relations with the local elite were marked by profound mistrust, which in turn justified the complete exclusion of Pisans from any position of real power. According to the historian Francesco Guicciardini, when Pisa handed over its keys to Charles VIII in 1494, the jurist Burgundio Leoli summed up the condition of his fellow citizens in these terms: ‘they were not admitted to any office or administrative role within the Florentine dominion, not even to those that were granted to foreigners’ [‘non essere ammessi a qualità alcuna di uffici e d’amministrazione nel dominio fiorentino, eziandio di quelle le quali alle persone straniere si concedono’]. This situation made Pisa the only territory over which Florence could exercise control without the need for any form of consent.

In the agreements concluded between Giovanni Gambacorti and the Florentine republic for the surrender of Pisa, it was in fact promised that the governance of municipal institutions would remain in Pisan hands, albeit restricted to the Bergolini faction alone, composed of merchants and shipowners who had historically favoured an open stance towards Florentine businessmen. The Raspanti faction, by contrast, which brought together citizens involved in manufacturing activities and concerned about Florentine competition, was to be excluded from government.

Gino Capponi—the Florentine commissioner and, for the eight months following the conquest, captain of the city—addressed the Pisan notables assembled in Palazzo degli Anziani on 9 October 1406, declaring that the new political arrangement would assign equal weight to both factions. This position of balance, however, remained purely nominal for two reasons. First, the effective strength of the two factions had dissipated with the loss of the leading figures who had sustained them. Second, the offices to which Pisans were admitted carried, in practice, extremely limited powers.

The Florentine republic was therefore free to reorganise the government in accordance with its own plan, based on the exclusive appointment of trusted Florentine figures. This direct form of rule was further reinforced by close supervision of ecclesiastical offices and of institutions of major importance, such as the Opera del Duomo and the hospitals.

In Florence, an office composed of ten Florentine citizens—the Decem Pisarum—was established, with the primary function of overseeing control of the city. In Pisa itself, Florentine authority was represented by the capitano di custodia e balìa, a post that replaced the former office of Capitano del Popolo, and by a podestà, who was no longer appointed by the Anziani but imposed by the dominant city. Both offices had a six-month term, and their holders—drawn exclusively from among Florentines—were required to maintain constant communication with the Decem Pisarum, to whom effective decision-making power was in fact entrusted.

Throughout the fifteenth century, the very existence of these two offices was experienced in Pisa as an imposition. The office of the podestà, in particular, was regarded as entirely superfluous by the Pisans, who were nevertheless obliged to provide a salary for its holder. As a result, the office was suspended repeatedly between 1432 and 1472, before being definitively abolished in 1491.

Given the nature of Pisa’s government, which depended on measures adopted by the Florentine republic and aimed at maintaining control over the city, on certain occasions, both the office of capitano del Popolo and that of the podestà were suspended, with their functions entrusted to a commissioner. This typically occurred in response to exceptional circumstances, such as moments of crisis—for example, the particularly severe malaria epidemic of 1464.

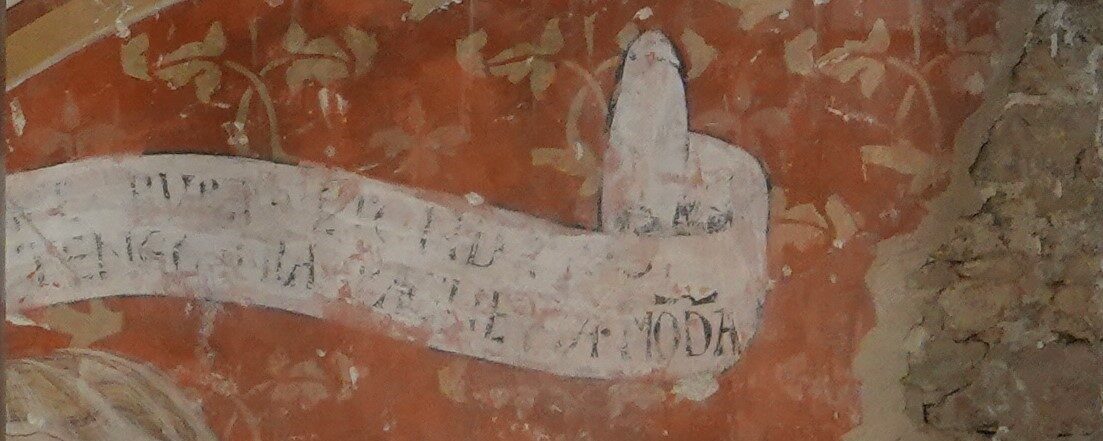

The ancient Council of the Anziani was replaced by a body composed of eight Priori, elected every two months from among Pisan citizens—two from each quarter—on the condition that the Bergolini and Raspanti factions be represented in equal numbers. This distinction remained in force until the 1430s. The Priors’ responsibilities concerned primarily fiscal matters. In practice, however, these were limited to the collection of the heavy taxes imposed by Florence on Pisa throughout the early phase of domination, since from 1406 the city had been deprived of the right to levy any gabella or taxation of its own. Undoubtedly, the office of Prior was the most important within the Pisan commune. It was based in the former Palazzo degli Anziani (now Palazzo della Carovana), where a fragment of a fresco depicting Truth in the Aula Bianchi can still be attributed to the patronage of the Priors. The building was later occupied by the commissioner of Pisa in 1509, and the Priors were transferred to the former Camera del Comune, subsequently converted into the present Palazzo dei Dodici.

In the second half of the fifteenth century, the consequences of Pisa’s impoverishment were clearly apparent in the depopulation and low productivity of its contado. In response, the Florentine government established in 1475 the Opera della reparatione del contado e della città di Pisa, a body overseen by a commissioner, which represented a first decisive step towards the city’s economic recovery.

After the brief experience of republican independence (1494–1509), Pisa capitulated once more. The renewed submission to Florence was formalised by an act of capitulation in 1510, which included certain concessions to the citizenry—such as the right to adopt new statutes and to elect the community’s magistracies—while nonetheless ensuring strict control by the dominant city, exercised via the capitano, the podestà (reinstated at this time), the four Consoli del Mare, and the commissioner of the Opera della reparatione.

This control eased slightly between 1530 and 1532. During the war and siege of Florence, the capitano and podestà were replaced by two commissioners, one of whom, in 1530, was Francesco Guicciardini himself. He drew attention to the situation of Pisa, whose economic recovery was thwarted by an inert and stifling governmental arrangement.

In 1534, under Duke Alessandro de’ Medici, the functions of capitano and podestà were concentrated in a single Florentine official known as the capitano e commissario di Pisa. This arrangement remained unchanged until the time of Duke Cosimo I, under whose principate a clear centralising tendency emerged, albeit one oriented towards the economic revival of Pisa. This revival was pursued through the establishment of the Otto provveditori sopra le cose di Pisa in 1542—a body that also included Guicciardini—and through the restoration of maritime and mercantile jurisdiction to the Consoli del Mare (abolished in 1533 and replaced by a single Provveditore delle Gabelle).

Media gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.