Galley Fragments

Serving as emblems of the Order of Saint Stephen’s mission as defender of the Christian faith, the small sculptures and monumental polychrome wooden reliefs preserved in Santo Stefano dei Cavalieri are decorative fragments from galleys—the multi-oared vessels used by the Knights in their maritime campaigns.

The pieces, identifiable with those mentioned in 1792 by Alessandro da Morrona as being ‘in an arsenal near the Porta a Mare’ [‘in un arsenale presso la porta a mare’] and probably dating from the reign of Cosimo III de’ Medici, between the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, are traditionally attributed to the Pisan master woodcarver Santi Santucci, known as il Santino. More recent studies, however, have revealed the involvement of several hands, indicating a broader contribution from the artist’s workshop, with Andrea Mattei proposed among the possible collaborators.

Mentioned again in 1838 by Ranieri Grassi as being kept in the same repository, the fragments—by then owned by the woodworker Cosimo Tronci—became the subject of correspondence in 1846 within the Order of Santo Stefano. They were described as ‘wooden low reliefs that once served as the lining of one of those ancient galleys, either those that the republican Pisans sent to fight the Saracens, or those manned by the knightly soldiers of Santo Stefano in their ever-glorious and most fortunate caravans; in either case they are rich monuments of naval art’ [‘ornati in basso rilievo di legno i quali hanno al suo tempo servito di fodera ad una di quelle antiche galere, o che i pisani repubblicani in corso spedivano contro i Saraceni, o che i cavalieri militi di Santo Stefano armavano nelle antiche loro caravane, sempre gloriose e felicissime. E nell’uno e nell’altro caso sono ricchi monumenti di arte navale’]. In August of that year, Tronci, moved by ‘patriotic zeal’ [‘zelo di patria’], sold the wooden decorations to the Order for eight hundred lire, declining an offer of one thousand lire from the French Minister of Defence, who had sought to acquire them for the naval arsenal at Toulon, so that ‘Pisa might not lose a classical monument recalling its maritime expeditions’ [‘onde Pisa non perda un classico monumento che le sue marittime spedizioni anche in quel senso può rammentare’].

Documentary evidence, partly collected and commented on by Alfredo Giusiani in the early twentieth century, confirms that the fragments came from at least two different vessels—though it is less likely, as has sometimes been suggested, that they derived from the so-called Peota dorata, a Medici ceremonial ship once used for the translation of Saint Stephen’s relics and later dismantled in the eighteenth century. These elements were repeatedly used as temporary decorations for the corsa delle fregate on the Arno, a traditional regatta still held in Pisa on the feast day of Saint Ranieri (17 June). Evaluated at the time of their sale as ‘works from the Medicean period, not from the earlier days of the Pisan Republic, as proposed by those wishing to acquire them’ [‘opere dei giorni medicei, non dei tempi più vecchi della Repubblica pisana, come vorrebbe chi ne propone l’acquisto’], the pieces, once acquired by the Order, were initially placed ‘as a noble document of history’ [‘come un nobile documento d’Istoria’] in the Sala delle Armi Gentilizie—now the Sala Azzurra—inside Palazzo della Carovana, before being moved to the nave of Santo Stefano in 1867, following the completion of restoration work on the church.

Flanking the high altar, beneath the organ lofts, are two eagles with powerful feathered wings and long necks. The one on the left (facing the altar) takes the form of a fantastical creature, more reminiscent of a vulture or the mythical dodo, which was not yet extinct in the seventeenth century. Both are missing a talon and rest on voluted bases clearly detached from larger panels, probably once used to decorate the sides of a ship’s prow. On the long walls, two smaller wooden sculptures depict male heads with long moustaches—identified, according to the visual conventions of the time, as Ottomans—set within asymmetrical volutes and broken weapons such as lances and arrows. This type of imagery was common on Medicean galleys; indeed, in 1600, Giovanni de’ Medici instructed Ruberto Lottieri, superintendent of the Arsenal, to have made ‘a head with a turban for the galley called bascia’ [‘una testa con un turbante per la galera bascia’].

On either side of the entrance portal, along the counter-façade, are two decorative wooden panels originating from different stern sections. One terminates in a lion holding a bezant adorned with gilded fleurs-de-lis between its forepaws, the other in a monstrous sea dragon. Both are composed of a succession of frames enclosing Turkish trophies and panoplies, interspersed with mascarons and cartouches. The horizontal wooden beam crowning the compositions like a cornice is surmounted, in one case, by an additional mascaron and, in the other, by a cannon.

In these two compositions, certain details—ranging from simple objects such as lanterns and Ottoman turbans displayed as trophies of victory to anthropomorphic motifs like a severed Turkish head clutched in the dragon’s claws or the face of a sub-Saharan youth incorporated decoratively into a panoply—reveal the brutal and discriminatory visual rhetoric of these wooden reliefs. This rhetoric is intensified in the two superimposed high reliefs on the right-hand wall of the church (with one’s back to the entrance). The lower panel, flanked by two threatening eagles surmounted by mascarons, shows an African woman on the left and a child on the right, while at the centre stand two chained men of differing skin tones, all surrounded by banners, lances, turbans, and arrows. The upper fragment, from which two banners extend, depicts a grim procession of chained captives—men and women, both African and Turkish—grotesquely caricatured: the women shown bare-breasted, the men with bulging eyes and contorted bodies in unnatural poses. The inclusion of an enslaved child is particularly disturbing. As also shown by the painted scenes on the church ceiling, enslaved people were among the most coveted spoils of the Knights of Santo Stefano. Their multi-ethnic depiction in these reliefs corresponds to contemporary accounts that describe three distinct groups aboard the Medicean galleys: captives from North Africa (lighter-skinned), those of sub-Saharan origin (darker-skinned), and Turks (depicted in the reliefs with prominent moustaches).

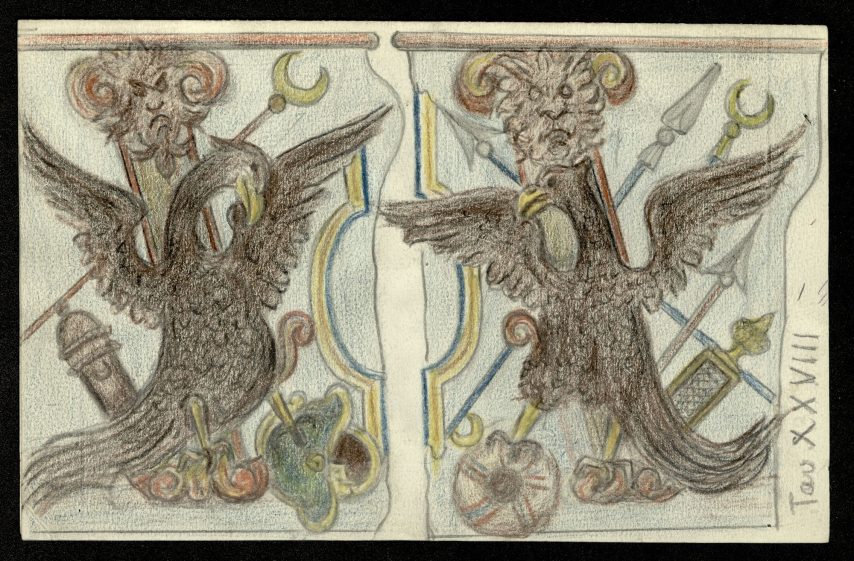

These fragments, disconnected from one another as they originated from different vessels, were assembled in the late nineteenth century into pastiches created for display and later rearranged in various configurations. A valuable series of pastel drawings by Alfredo Giusiani, dated 1933, records a wall arrangement that differs from today’s. Archival documents held in the Soprintendenza of Pisa reveal that in 1892 a second wooden lion, described as coming from Santo Stefano, appeared on the Florentine antiques market and was illustrated in the corresponding sales catalogue, its features closely resembling those of the lion incorporated into the wall panel now in the church. Just over a decade earlier, the State Property Office had authorised the sale, at reduced prices, of several furnishings from the church, which were at that time stored in its warehouses.

From a conservation perspective, records show that in 1916 all the wooden elements were cleaned and treated. Further routine conservation and dusting of the wall panels took place in the late 1980s, and in 2000 the two eagles still flanking the high altar underwent conservation treatment.

Media gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.