Reception Among Travellers

late 16th - late 19th century

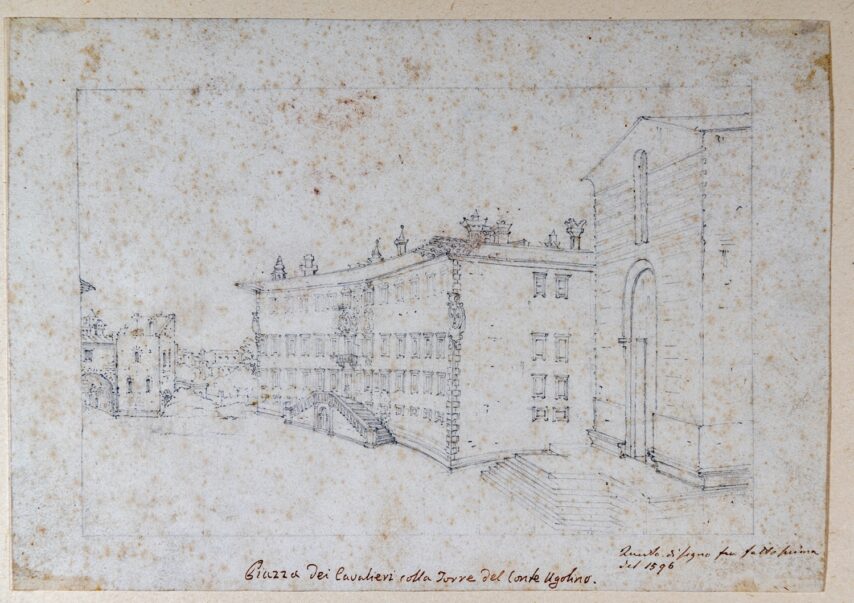

Shortly before the Tower of Famine disappeared from view in Piazza dei Cavalieri, it was mentioned—perhaps for the last time among known testimonies—by the distinguished traveller Robert Dallington, who in his Survey on Tuscany (1605) recalled its ruinous state during his 1596 visit to Italy: the ‘old ruinous Tower’ where the tragedy of Ugolino, narrated in Canto XXXIII of Dante’s Inferno, had taken place. Dallington’s account once again confirms how, well into the early modern period, the reception of this otherwise anonymous medieval structure continued to be shaped by the spotlight cast on it by the Commedia. In the early seventeenth century, what remained of the tower was incorporated into the right wing of the newly constructed Palazzotto del Buonomo—later renamed Palazzo dell’Orologio—an event that coincided with the beginning of what literary historians have termed the ‘century without Dante’.

Although the idea of a ‘century without Dante’ is something of an overstatement—since Italian and European intellectuals, particularly in France, continued to read, cite, and appreciate the Commedia for its poetic and linguistic value—publishing records nonetheless indicate a decline in the poem’s circulation. In the seventeenth century, only three editions were published, all between 1613 and 1629. Piazza dei Cavalieri, thoroughly transformed and resplendent with Medicean grandeur and the prestige of the Order of Knights of Saint Stephen—then at the height of its military might, following the capture of Bona in 1607—now eclipsed the waning myth of Ugolino and the Tower of Famine. In 1632, however, the Dantesque episode found an unexpected revival in Il Conte Ugolino, a tragedy by the Urbino-born writer Giovan Leone Sempronio (though it would not be published until 1724, after his death). In the play, Sempronio offers a novel interpretation of the Tower’s function: originally conceived as the repository of Ugolino’s personal treasure, it is transformed into a prison by Archbishop Ruggieri degli Ubaldini as an act of poetic justice.

Gift of Michael A. and Juliet van Vliet Rubenstein in honor of the 75th anniversary of the Morgan Library

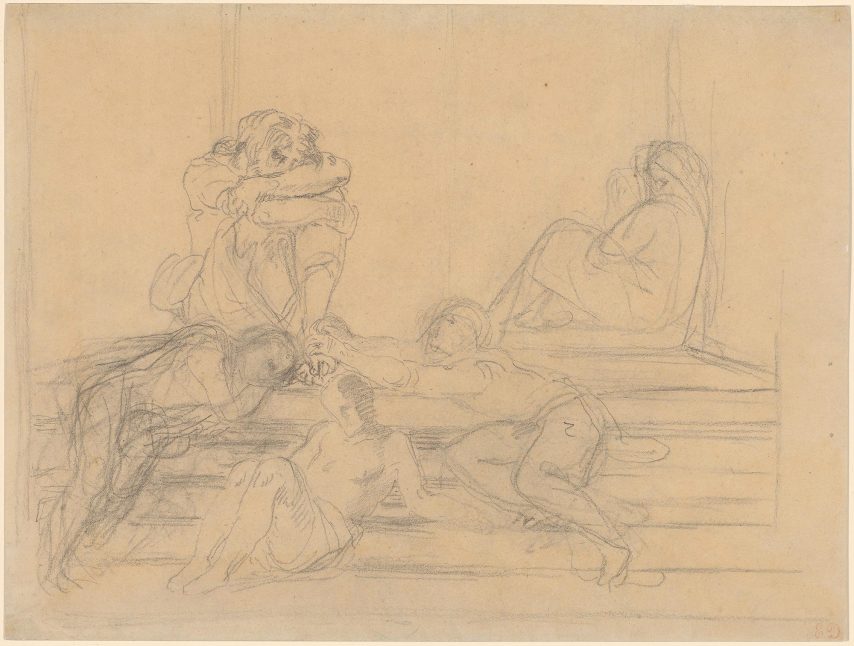

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the declining role of the Knights within the new grand-ducal order—driven partly by dynastic succession and partly by changing international circumstances—coincided with a revival of interest in Dante’s Commedia and a renewed taste for medieval heritage. In this context, the medieval character of Piazza dei Cavalieri once again came into focus. The renewed fascination with the episode of Ugolino della Gherardesca and the site of his death gave rise to a rich body of artistic responses, ranging from eighteenth-century theatrical works to nineteenth-century visual reinterpretations in both painting and sculpture by artists such as Eugène Delacroix and Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux. By this time obscured for nearly two centuries, the Tower of Famine became the object of widespread curiosity among European travellers on the Grand Tour. From the late eighteenth century through the nineteenth, diaries, letter collections, and travel narratives are filled with references, conjectures, and more or less credible hypotheses about the tower’s original location, based on local hearsay or on the interpretation of low walls and scattered ruins around Pisa.

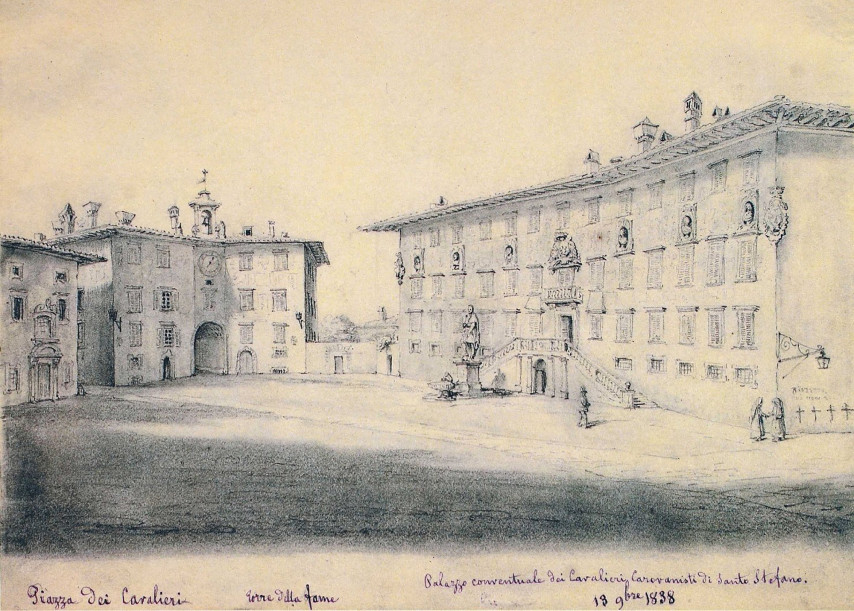

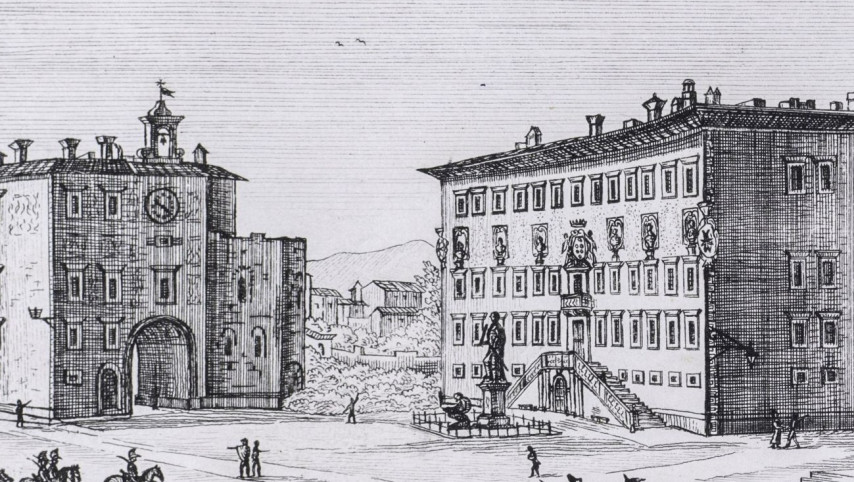

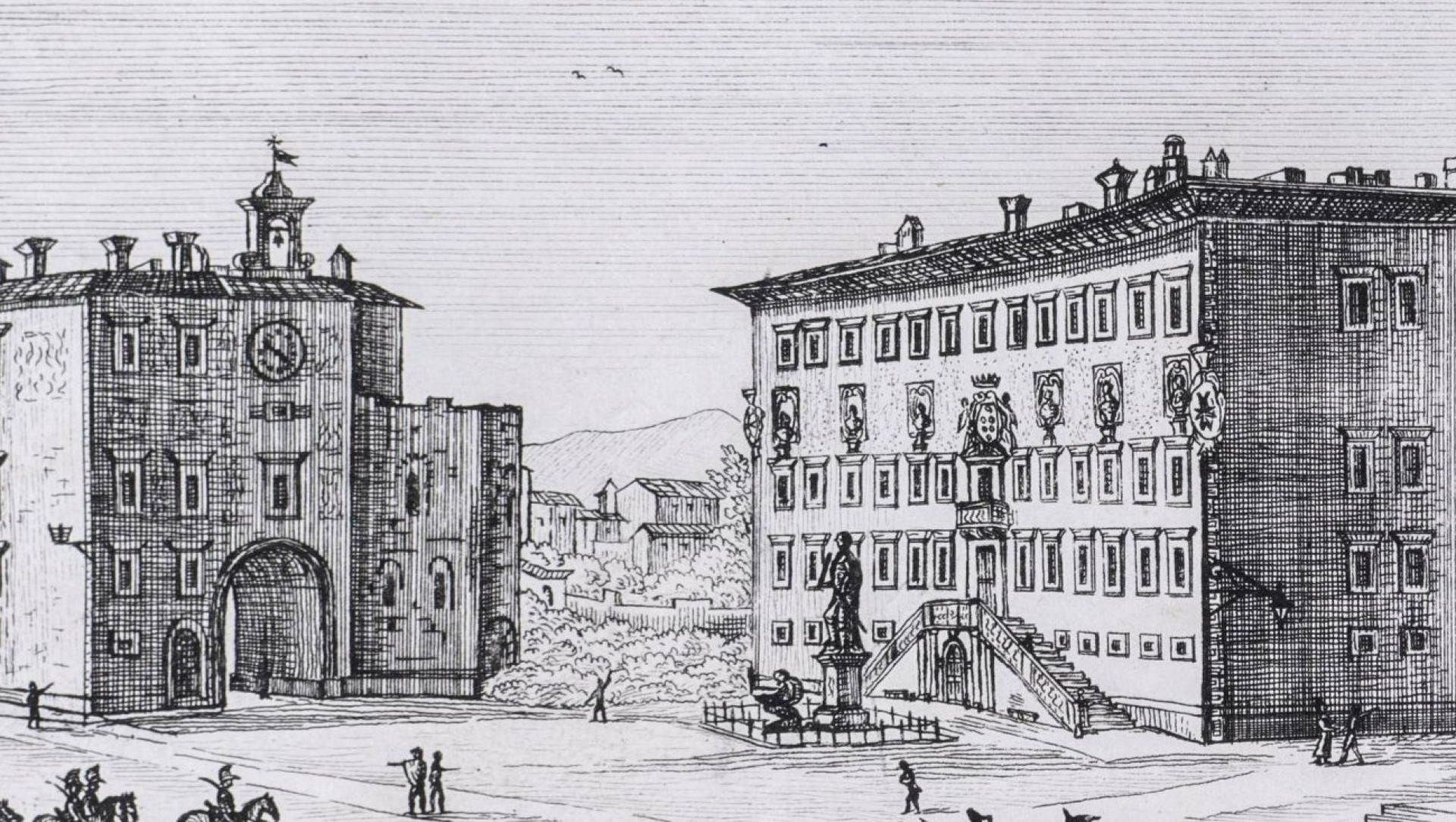

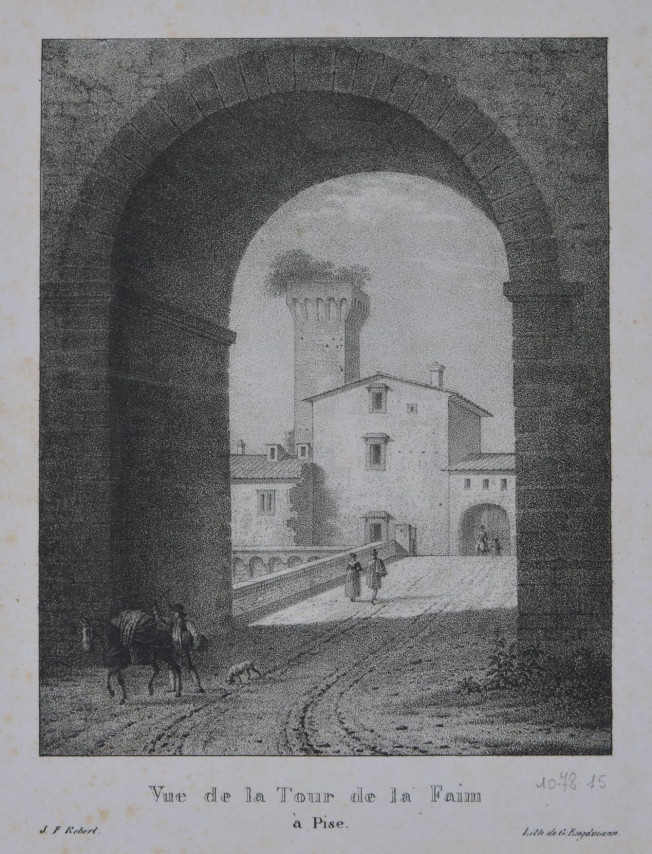

Drawn by the allure of the Lungarni and the Cathedral, and armed with copies of Dante’s Commedia rather than conventional city guides, the celebrated writers and intellectuals who visited Pisa in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were chiefly in search of the Tower of Famine. Piazza dei Cavalieri—depicted as nearly deserted in an 1838 drawing by Adèle Poussielgue—was visited almost exclusively for this reason. In 1791, the poet Friedrich Leopold zu Stolberg-Stolberg noted: ‘No trace of it remains, and there is still debate as to the precise location of the site where it once stood’. In 1799, the German traveller Ernst Moritz Arndt believed he had found the tower in ‘an ancient masonry structure’ next to Palazzo della Carovana, ‘fitted at the base with a dreadful iron grate’, and imagines Ugolino’s atrocious banquet. Leigh Hunt, friend of Shelley, Keats, and Byron, recalled in his Autobiography (1850) that as early as 1822 there was lingering uncertainty about the tower’s exact location. In La Grèce, Rome et Dante: Études littéraires d’après nature (1848), Jean-Jacques-Antoine Ampère mapped out a literary journey through Dantean sites across Italy, rightly placing the Tower of Famine in Piazza dei Cavalieri. Local studies offered further support. In 1834, Bartolomeo Polloni published a compelling print that reconstructed the appearance of the tower by replacing part of the then-modern Palazzo dell’Orologio with its presumed earlier form.

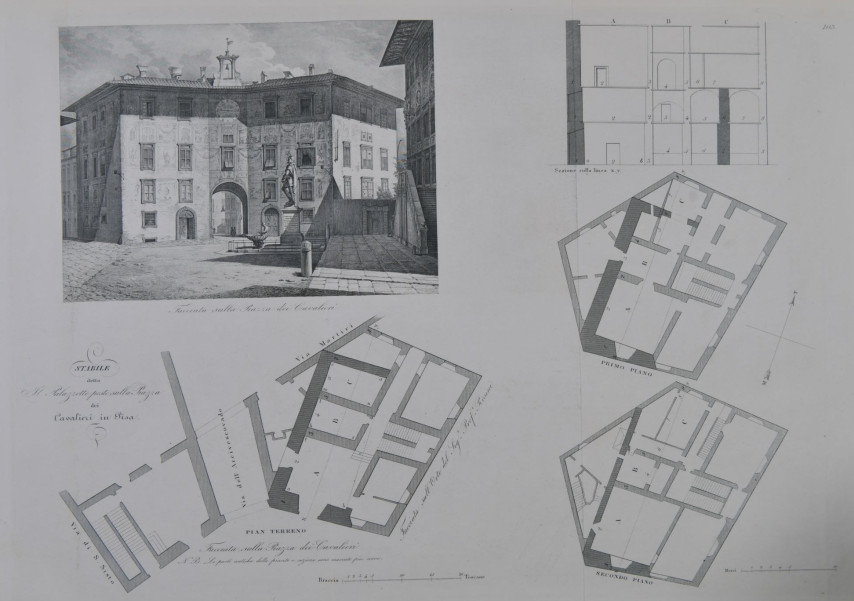

Research intensified in the mid-nineteenth century. Between 1858 and 1865, Lord George John Warren Vernon’s monumental edition of L’Inferno di Dante presented a detailed survey of Dante’s prison, supported by extensive documentation—including sixteenth-century maps and a request made as early as 1847 to the architect Tito Della Santa to survey and cross-section the Palazzotto in order to approximate the original footprint of the Tower of Famine. By 1867, the American author William Dean Howells, in his Italian Journeys, identified the Muda—another name for the Tower of Famine—as one of the city’s most compelling sites, which in his account even outshone the monumental piazza of the Cathedral.

Prompted by the wealth of European literary and visual works devoted to Dante’s celebrated episode from the late eighteenth century onwards, these Romantic evocations—together with the earliest exploratory inquiries into the structure of the Palazzo dell’Orologio—would, by the early twentieth century, give way to archaeological investigation and to the tower’s definitive rediscovery within the Palazzo dell’Orologio.

In reality, the lithograph depicts the entry to the Cittadella in Pisa

Palazzo dell’Orologio

Main EntryMedia gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.