Quadrifora

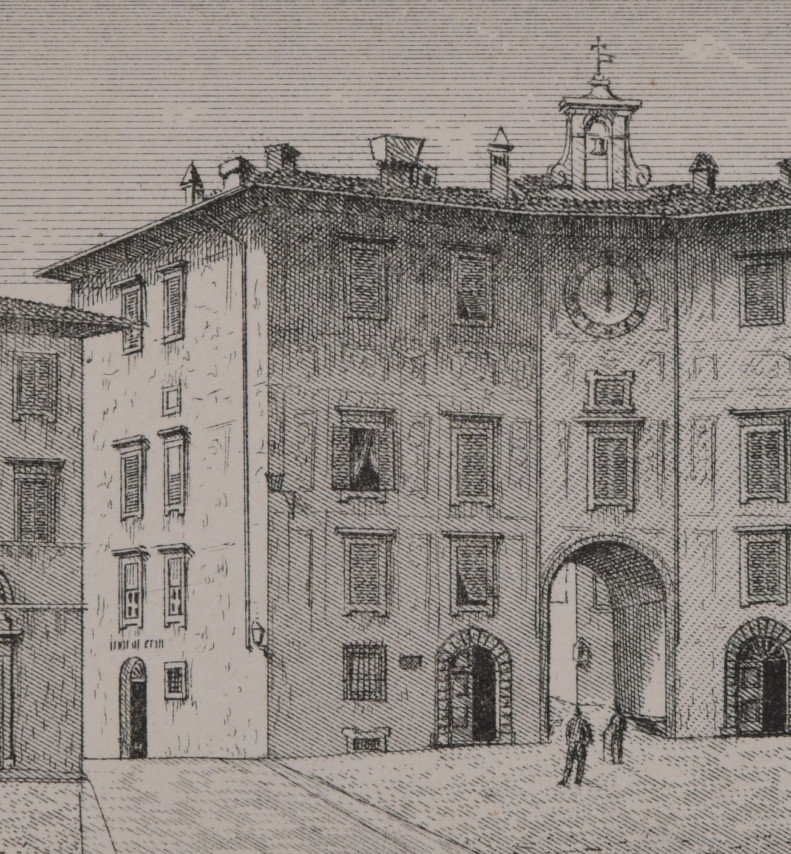

In 1919, in preparation for the celebrations marking the six-hundredth anniversary of Dante Alighieri’s death (1321–1921), the then Superintendent of Pisa, Peleo Bacci, sponsored several important restoration works in Palazzo dell’Orologio. Like other Italian monuments subject to restoration campaigns during those years, the building was directly linked to Dante’s narrative, incorporating within its seventeenth-century structures the Tower of Famine, recalled by the poet in Canto XXXIII of the Inferno as the site of the tragic death of the Pisan count Ugolino della Gherardesca. In that same year, the building—owned by Count Eugenio Finocchietti and recently placed under the protection of the Superintendency—was sold to Alberto della Gherardesca, a descendant of the illustrious thirteenth-century statesman.

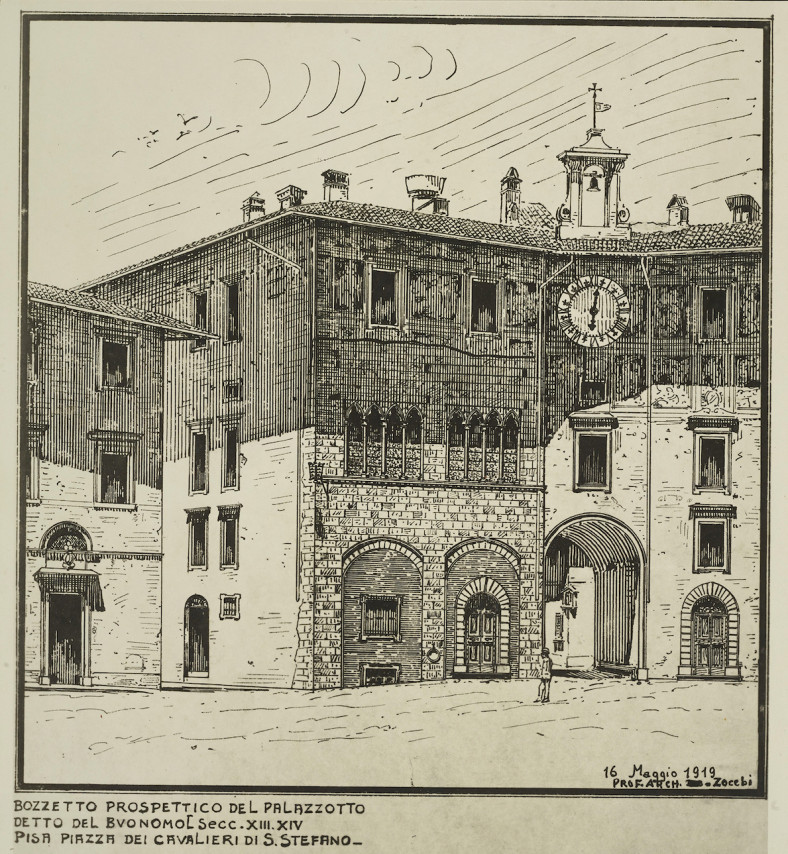

In line with a broader trend towards neo-medieval revival that characterised early twentieth-century Pisa, Bacci — in agreement with the incoming owner of the property, and in fact even before the sale had been finalised — promoted exploratory surveys on the external walls. These revealed, as he later reported to Finocchietti, ‘traces of two arches with dentil-worked ashlars at ground-floor level on the façade, and traces of two mullioned windows with marble colonettes and lobed archlets superimposed on the said arches’ [‘le tracce di due arconi con conci lavorati a dentelli al piano terreno della facciata e tracce di due polifore con colonnette in marmo e archetti lobati, a detti arconi sovrapposte’]. It was therefore decided to intervene in order to restore the building’s original medieval appearance, not only by recovering the surviving fragments but even by executing new stylistically congruent decorations in the interior spaces – often, indeed, at the expense of preserving features pertaining to the Medici period.

On the left wing of the building, in addition to exposing the blocks (made from local verrucano stone) that formed the ancient wall fabric, it was decided to reinstall the two quadriforas, the partial remains of which had emerged during the surveys. After commissioning several reconstructive drawings from the architect Oreste Zocchi, Bacci turned to Edoardo Marchionni, director of the Regio Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence, requesting assistance with the operation and the dispatch of a technician to take casts of the recovered fragments, so as to study possible integrations more effectively. Following the appointment of Pietro Capecchi, however, it soon became clear not only that it would be preferable to work directly on the originals — listed by Bacci as ‘two capitals, two bases, two Gothic archlet supports to be restored and kept as models for the reintegration’ [‘due capitelli, due basi, due reggi archetti gotici da restaurare e da tenere per modelli nel reintegramento’] — which were packed into two crates and sent to Florence (where the superintendent himself travelled to plan the intervention more thoroughly), but also that it would be impossible to re-erect both mullioned windows, necessitating a fallback to just one.

The marble required for the replacements was ordered from the Florentine firm Sollazzini, and its working continued through the early months of 1920. As early as January, however, Marchionni informed the Pisa superintendent that the materials had arrived: ‘the column bases are finished. The three lobed spandrels are in progress, and two column shafts have been roughed out, the third almost so; but we cannot complete them until we have the old shaft, so that we can see how the final chisel pass was made and, in the meantime, restore it’ [‘le basi delle colonne sono fatte. I tre pennacchi lobati sono in lavorazione e due fusti di colonna sono abbozzati, il terzo quasi, ma non possiamo finirli fintanto che non avremo il fusto vecchio per vedere come è data l’ultima passata di scalpello ed intanto restaurarlo’].

In addition to the dispatch of the missing components needed to complete the remaining pieces, Bacci was pressed to arrange the definitive trial fitting of the window, with any necessary adjustments carried out on site. Work at the Opificio concluded in May, when the finished elements were transported to Pisa. However, the actual installation required several further months.

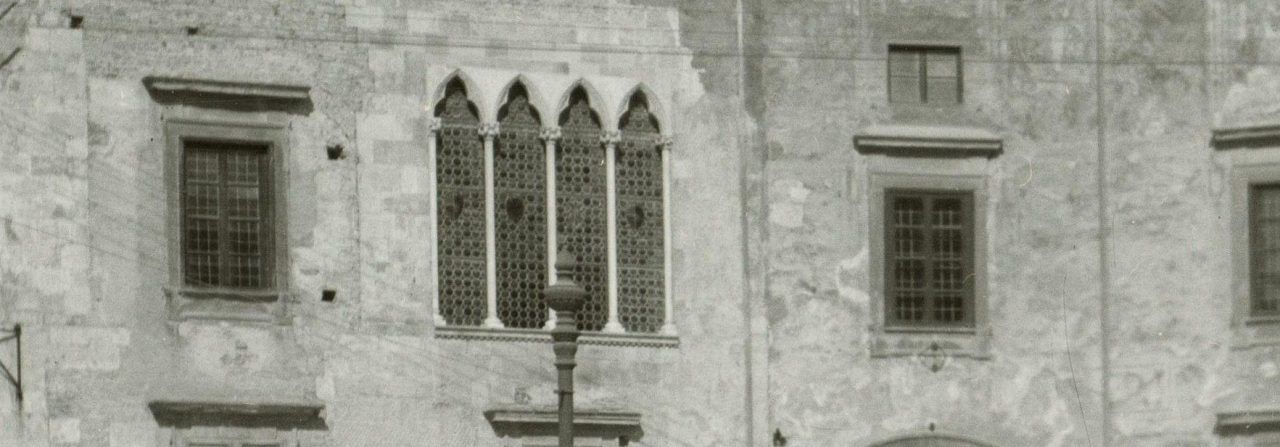

Only in the following August could the superintendent inform Marchionni that the four-light window had been positioned—describing it as ‘a most successful piece of work and a testament to the skilled craftsmen of that Royal Workshop and its knowledgeable director’ [‘lavoro riuscitissimo e segno dei bravi artefici di codesto Regio Opificio e del suo sapiente direttore’]—while also announcing its imminent public unveiling. Still lacking, the glass panes were commissioned from the painter Ettore Giovannozzi of the Florentine stained-glass firm De Matteis, whereas the associated iron armatures were produced by the blacksmith Salvatore Magherini.

Final assembly took place in November 1920 and was carried out by Napoleone Chini, head of a long-established family firm active throughout the local area.

It was at this juncture, however, that disagreements arose between Bacci and the owner, Della Gherardesca — who had assumed the financial burden of the latest works and had also requested that his coat of arms be placed on the new window glazing. The count refused to settle the invoice submitted by Chini while simultaneously pressing the Superintendency to authorise the opening of a window on the right wall of the vault connecting the two wings of the building, in symmetry with the one already present on the left side. The superintendent’s obstinate silence, evidently stung by the Chini affaire, triggered a dispute. This culminated in an accusation against Bacci of having caused, through the reintegration of the quadrifora, ‘an anachronistic intrusion of Gothic elements into a structure of now indelible sixteenth-century character’ [‘una intrusione anacronistica di elementi gotici in una fabbrica di ormai indelebile carattere cinquecentesco’], a wording found in the draft complaint prepared for the count by his friend Luigi Dami, editorial secretary of the journal Dedalo, directed by Ugo Ojetti, as well as of having failed to agree the costs.

After a protracted standoff, in which influential figures such as Ojetti himself and the deputy Nello Toscanelli rallied in support of Della Gherardesca, it was Bacci who finally yielded, compelled by higher orders to grant authorisation for the opening of the window (which was, in fact, never carried out). The Ministry then settled Chini’s invoice on 24 October 1924.

The quadrifora, still preserved today, effectively disrupted the visual and formal continuity of Palazzo dell’Orologio façade by replacing the pre-existing window. Its presence has nevertheless become historicised, and the Scuola Normale Superiore’s attempt — following its purchase of the building and the commencement of its comprehensive restoration in the 1970s — to obtain clearance from the Superintendency for the reinstatement of the original sixteenth-century opening proved fruitless.

Palazzo dell’Orologio

Main EntryMedia gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.