Pre-Existing Church: San Sebastiano alle Fabbriche maggiori

On 3 January 1563, in a letter to Bartolomeo Gondi, Giorgio Vasari wrote: ‘Meanwhile I am laying out the lines for the church of the Knights’ [‘Intanto io tiro le corde alla chiesa de’ Cavalieri’]. The church in question—the present-day Santo Stefano—existed at that point only as a project. The site on which it was to rise was still occupied by properties owned by the Pisan citizens Giuseppe Perini, Niccolò and Bartolomeo Avarna, and Vincenzo Caprile, together with an older religious building, San Sebastiano, known as alle Fabbriche maggiori. This former church, already deconsecrated, was demolished in the two years preceding the laying of the foundation stone for the new conventual church on 17 April 1565.

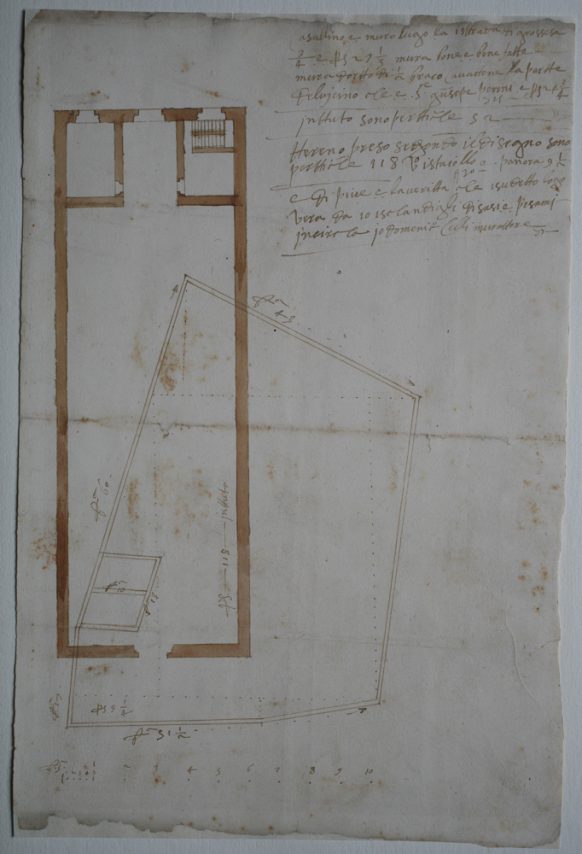

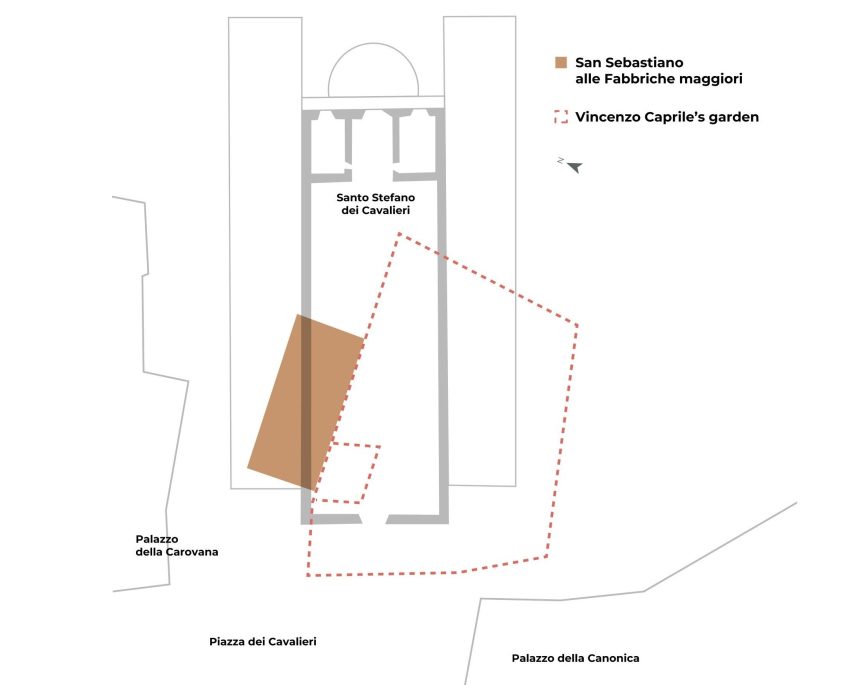

Today, reconstructing the original appearance of this lost sacred building remains difficult. In the medieval period, however, it occupied a central position within the city’s road network and lay in close proximity to the important political centre of Piazza degli Anziani. Ewa Karwacka had already argued, on the basis of a drawing showing the plan of the church together with a survey of Vincenzo Caprile’s garden carried out by the mason Domenico Celli in 1569 (now preserved in the Archivio di Stato di Pisa), that the ground-plan extent of the earlier structure was considerably smaller than that of the new Vasarian church. Subsequently, Francesca Anichini and Gabriele Gattiglia proposed locating the medieval church—aligned on an east–west axis—to the north of the aforementioned garden, in the area corresponding to the junction between the left (seventeenth-century) wing and the Vasarian nave of Santo Stefano. Archival documentation, together with several recent excavations in the area, provides the limited information currently available.

Graphic rendering by Zaki Srl

Based on F. Anichini, G. Gattiglia (a cura di), Nuovi dati sulla topografia di Pisa medievale tra X e XVI secolo. Le indagini archeologiche di piazza S. Omobono, via Uffizi, via Consoli del Mare e via Gereschi, ‘Archeologia Medievale’, 35, 2008, pp. 121-150, in particular p. 129

The earliest documented reference to the church dates to 21 August 1074. This constitutes a terminus ante quem for its foundation, which, as Gabriella Garzella suggests, must therefore be of earlier date. San Sebastiano thus forms part of a group of religious buildings that, on the basis of surviving documentation, appeared between the 1070s and 1080s, including San Felice, Santi Giusto e Clemente, San Bartolomeo degli Erizi (on the site of the present-day Piazza delle Vettovaglie), Santa Maria Vergine, and San Sisto—the only one whose date of foundation is known with certainty (1087).

Less than a century later, in the Vita Sancti Raynerii of 1160, the church is recorded with the attribute ‘de Fabricis’, reiterated in 1189, perhaps in order to distinguish it from another church dedicated to San Sebastiano that had meanwhile been founded in Oltrarno, to the south of the present-day Logge di Banchi. The document of 1189 refers to a citizen named Stefano, described as a faber: one of several clues that allow us to discern the occupational specialisation of the district situated between San Sebastiano and the church of San Felice. The attribute ‘de Fabricis’ (or ‘delle/alle Fabbriche’) thus refers to the dense concentration in the area of workshops engaged, at various stages, in metalworking, as well as to the dwellings of the artisans involved, an interpretation corroborated by recent excavations beneath Palazzo della Canonica. A revealing snapshot of this context is provided by the oath sworn in 1228 by 4,300 Pisans to seal the alliance with Siena, Pistoia, and Poggibonsi: among the faithful associated with San Sebastiano, fifteen men were engaged in metallurgical activities (58 per cent of the professions recorded), compared with twelve at San Pietro in Cortevecchia and five at San Sisto. By 1305, the Breve dell’Arte dei Fabbri had been drafted, approved, and publicly read in San Sebastiano.

These documentary attestations are confirmed and complemented by evidence emerging from three campaigns of preventive archaeological excavation (1993, 2007, 2013). The investigations encompassed the area in front of the façade, as well as the left and right sides of the Church of Santo Stefano, tracing occupation back to the early medieval phases of the settlement. These phases are characterised by the continuous and widespread presence of metallurgical activities, attested by slag, tools, and working structures—predominantly associated with iron—from the seventh to the fourteenth century. In the area directly in front of San Sebastiano, the more intensive ironworking activities came to an end between the late eleventh and the early thirteenth century. To the south of the church, however, in a position set back from the ‘via di San Felice’ (present-day Via Ulisse Dini), metallurgical production continued until the mid-fourteenth century, shifting from iron to bronze. These changes in production accompanied significant urban transformations. Following the enlargement and repaving of Piazza degli Anziani, completed by the first half of the fourteenth century, the area between Via Consoli del Mare and Via Ulisse Dini—formerly part of a secondary, neighbourhood road network—acquired a new centrality and was therefore subjected to the same requirements of urban decorum as the newly configured space of civic self-representation of the Comune.

The proximity of San Sebastiano to Palazzo degli Anziani endowed the church with additional public roles beyond those linked solely to the Ars Fabrorum. These functions were connected in particular with the activities of the Anziani and their entourage, including the marrabesi, armed guards who were also accommodated in the surrounding area. According to the Fragmenta, in 1288 the Senate of the Pisan Popolo is said to have assembled in the church to decide the fate of Ugolino della Gherardesca, who at that time had barricaded himself in the neighbouring Palazzo del Popolo, then serving as the residence of the Capitano.

Excavations also brought to light a medieval find: a brick-lined well located near the left-hand corner (from the viewer’s perspective) of the façade of Santo Stefano, at the junction between one of the roads that crossed the piazza from north to south and the thoroughfare later known as Via Consoli del Mare. The well remained in use during the sixteenth-century construction phase in the area. At that time, when connected to a square basin, it may have served in the production of slaked lime for the building activities then underway. Once the works were completed, the well was filled in and sealed in order to level the entire piazza once again, as had already occurred more than two centuries earlier.

Media gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.