High Altar

Motivated by the generosity his predecessors had shown towards the conventual church, Cosimo III de’ Medici commissioned the altar. Executed between 1700 and 1709 to a design by Giovanni Battista Foggini, it is an exquisite Baroque work in polychrome marble, porphyry, and bronze. The altar contains two relics of Saint Stephen, third-century pope and martyr: a fragment of his body, secured in 1682 from the civil and religious authorities of Trani through a papal brief from Innocent XI Odescalchi; and his cathedra, presented to Cosimo by Innocent XII Pignatelli in 1700.

The imposing structure consists of a porphyry sarcophagus that contains the bones of Saint Stephen, visible through a small window, and a tall bronze throne, which serves as a reliquary for the cathedra on which the saint sat shortly before his martyrdom, positioned above the sarcophagus. The elegant backrest, adorned with volutes, features a relief depicting the saint’s decapitation.

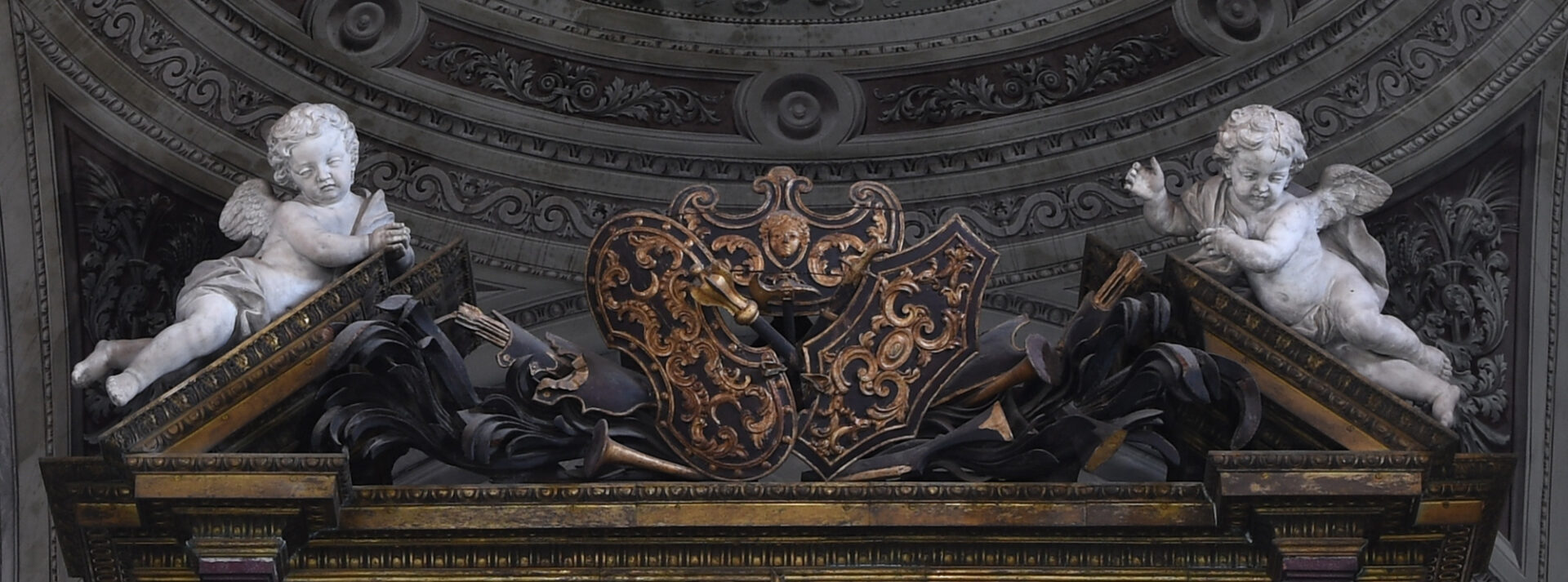

Above the double reliquary stands the marble figure of Pope Stephen, supported by clouds and putti and encircled by the gilded bronze rays of the Glory. He holds in his left hand the cross of the Order that bears his name, while his right is raised in a gesture of blessing. On the volutes of the sarcophagus rest two figures in Carrara marble, shown in adoration of the saint: the one on the left, bearing a banner, has been identified by scholars as a personification of Victory; the one on the right, with sword and shield, has been interpreted as an allegory of the Order of Saint Stephen. Contemporary documents, however, describe both simply as angels, noting their masculine features and small, barely visible wings.

The architectural structure, featuring double fluted columns, is made of the same reddish-brown porphyry with white veining as the sarcophagus. The base incorporates slabs of jasper and chalcedony, set within profiles of gilded bronze. Cornices, capitals, and other decorative elements are likewise crafted in gilded bronze. The only components executed in less precious material are the trophies on the pediment and the four flame-shaped vases above the columns, made of wood and subsequently painted.

The key to interpreting the entire image is provided by the inscription on the altar frontal, which reads: ‘NOMINI MEO ADSCRIBATVR VICTORIA’, a reference to the military character of the Order.

The altar’s current form emerged after nearly forty years of design evolution, following unrealised Vasarian proposals and a temporary late sixteenth-century wooden ciborium, later removed. Several important artists contributed to the development of the final structure, including Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Pietro da Cortona, Ciro Ferri, Pier Francesco Silvani, and Giovanni Battista Foggini, who built on Silvani’s designs. Beyond economic and practical considerations, the various designers also had to contend with the evolving status of the altar, which gradually came to serve as a reliquary, beginning with the grand translation procession through the city and Piazza dei Cavalieri on 25 April 1583. That event concluded at the altar of the church, where the large wooden group—later installed and traditionally attributed to Giovanni Battista Foggini—would eventually be placed. The project, stalled after Silvani died in 1685, was revitalised by the donation of the cathedra to Cosimo in Rome at the start of the new century.

The construction work took place between 1703 and 1707, under the full supervision of Giovanni Battista Foggini, who also produced a model in wood and wax—now lost. The current whereabouts of the terracotta models of the figures are unknown.

The Order covered the cost of the metal and labour, totalling 19,000 scudi. At the same time, the Grand Duke personally donated the marbles—porphyry, jasper, and chalcedony—and the gilding, valued at a further 16,000 scudi. One column was taken from the high altar of Pisa Cathedral, in exchange for which it received a two-part replacement fitted with a richly carved capital.

The altar’s final cost rose to 35,620 scudi, a testament to the preciousness of its materials. As Klaus Lankheit noted, the use of porphyry was regarded as a true offering to God—its complex carving, perhaps not without symbolic intent, entrusted to Muslims held in slavery held by the Order and carried out at the Pisan Arsenal. Archival sources cited by Riccardo Spinelli highlight the role of the stonemason Piero Corsi in these operations. Critics have observed that, given the chronology, Giovanni Battista Foggini was unlikely to have personally participated in carving the marble statues. This view was later supported by archival evidence pointing to the substantial involvement of the Carrara-born sculptor Andrea Vaccà in their execution.

In conceiving the altar, Giovanni Battista Foggini appears to have drawn on the model of Bernini’s Cathedra Petri in St Peter’s Basilica, particularly in the use of a curved backrest enclosing a figured relief—an echo of the Roman influences that shaped his artistic training. For the figure of the executioner in the relief, Foggini instead looked to another prominent figure of Baroque Rome: the Bolognese sculptor Alessandro Algardi, author of the marble group depicting the Decapitation of Saint Paul for the high altar of the church dedicated to the saint in Bologna—also a relief, though one that represents the moment after the martyrdom. The altar of Santo Stefano thus affirms Cosimo III’s vision in founding a Florentine academy in Rome, to keep the artists of his court in touch with the art of the Eternal City.

Media gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.