Two Models

17th and 19th centuries

The church of Santo Stefano dei Cavalieri was completed with a façade designed by Don Giovanni de’ Medici, a solution that remained largely faithful to Vasari’s original conception, as demonstrated by the model displayed in the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo. Yet despite this completion, the church continued to be the subject of numerous proposals for enlargement or reconfiguration until the early twentieth century. This long history of debate can readily be summarised as a tension between the preservation of the austere, conventual minimalism of the sixteenth-century building and recurring demands for liturgical adaptation in line with the prevailing architectural tastes of successive periods in Europe.

The two most significant moments in this debate are recorded by two further models, both preserved in the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo. Executed in wood and an imitation marble plaster known as scagliola– albeit in markedly different proportions . Both models are of considerable scale and painted with the deliberate intention of mimicking the materials envisaged for the finished building. This in itself represents a significant departure from the late sixteenth-century maquette of the façade alone, which is essentially monochrome and simply varnished.

The first model is substantially intact and in good condition, apart from the loss of a few ornamental details in scagliola. It vividly conveys the project drawn up by Pier Francesco Silvani in 1682, at a late stage in his career – he was to die only three years later, in 1685, near Pisa itself – which had begun more than forty years earlier in Florence alongside his father Gherardo. Gherardo and Pier Francesco Silvani were valued by the local aristocracy for their skill in modernising buildings that carried strong civic and familial identity – palazzi and monumental chapels – while keeping them, in both style and typology, within a recognisable Florentine tradition. In the field of liturgical architecture, Pier Francesco directed some of the most important Baroque building sites in the city: Santi Michele e Gaetano (with his father), the Oratory of Saint Philip Neri (succeeding Pietro da Cortona), San Frediano in Cestello, the high chapel of Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi, and the cathedral itself.

With this wealth of experience behind him, Pier Francesco Silvani’s project for Santo Stefano displays unmistakable stylistic traits. These include the block-like, traditionalist planimetric layout of the building, which leads to the conception of individual chapels as square-plan units crowned by shell domes with tall lanterns. They also include the retrospective choices in ornament – notably the systematic use of fluted Corinthian pilasters, reminiscent of Brunelleschi, and an abundance of Michelangelesque motifs in the details of pedimented aedicules or window surrounds, as well as ribbed half-domes reminiscent of St Peter’s in Rome – combined with Cortonesque insertions such as the projecting cantorie (choir galleries) on free-standing columns or the concave wings added to the façade. Finally, there is the distinctly grand-ducal taste for polychrome marble revetments, on which the painted surfaces of the model dwell insistently and which are perhaps the most characteristic feature of seventeenth-century Tuscan architecture. In terms of the building’s layout, the addition of two large domed side chapels opening onto the single nave through full-height arches – exactly like the apsidal space – would in practice have produced a cruciform and therefore markedly centralised interior, diverging substantially from the existing church. The proposal may recall the earliest seventeenth-century enlargement schemes – already attributed to Paolo Guidotti – which had likewise focused on the presbytery area with comparable layouts.

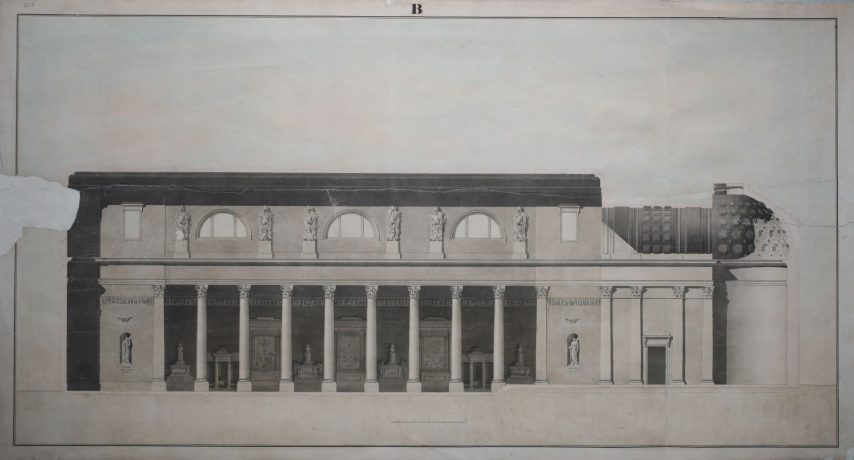

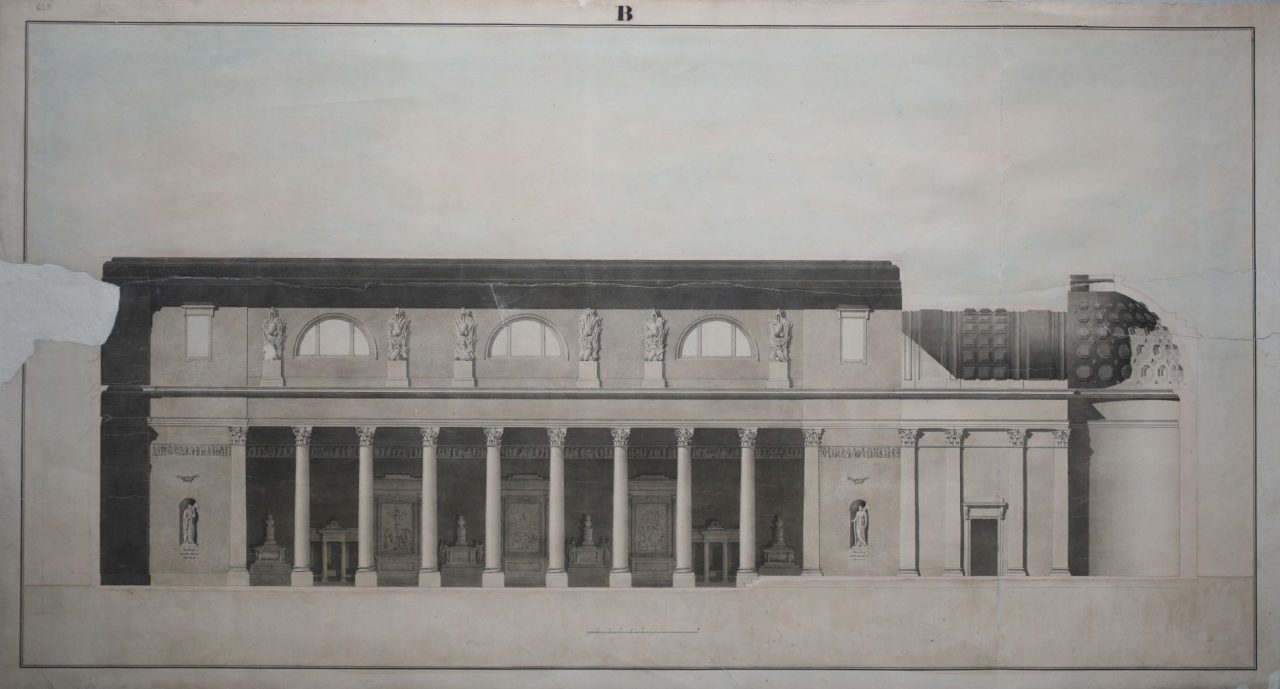

The only practical result of Silvani’s proposal – albeit in markedly different form – was the construction by 1688 of the lateral wings used as vestries. His ideas, however, continued to be invoked repeatedly, at least until the Restoration period, by the more ambitious architects, only to encounter consistent opposition from the majority of the Stephanian knights. Ultimately, it was precisely from the recurring conflicts within the Order of Saint Stephen that the nineteenth-century project preserved in the model also arose. That scheme was devised by Pasquale Poccianti, an official of the Regie Fabbriche and a leading figure in the Leopoldine Neoclassical period. His initial commission had been to evaluate another radical redesign – Alessandro Gherardesca’s project of 1840 – which was abandoned when the grand-ducal architect imposed his own alternative. The model in the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo – currently dismantled and awaiting conservation but still clearly readable – bears the date 1855 and thus represents the final version of the design. Poccianti developed it between 1852 and 1853 in order to avert the risk of a substantial scaling-back of modernisation initiatives (and the appointment of yet another rival architect, this time the Florentine Niccolò Matas). The episode confirms the primarily promotional and demonstrative, rather than strictly projective, function of such an object.

Even in the bold transformation proposed for the church, Poccianti – an architect ever faithful to his own vision – does not conceal his preference for a style that, by mid-century, had become distinctly backwards-looking and retardataire. It looks back to European experiences of at the latest the early nineteenth century, confirming what Franco Borsi has called ‘a culturally autonomous native Florentine’ [‘fiorentino autoctono e autonomo culturalmente’]. The articulation of the surfaces in Poccianti’s reimagined church accordingly hinges on a deliberate contrast between broad, emphatically plain expanses and zones in which chiaroscuro ornament is concentrated: the great barrel vault and the apsidal conch, for instance, carved with coffers, garlands, and festoons, or the relief-carved archivolts on the counter-façade. On this occasion, the chiaroscuro potential of monochrome treatment is fully exploited.

India ink and watercolour on paper, not signed nor dated

The orders – Corinthian for the nave and side altars, Ionic in the two vestibules and on the organ balcony – are predominantly carried on free-standing supports, whether columns or rectangular piers. The horizontal mouldings, kept minimal and barely projecting, run uninterrupted around the entire space, binding it together and emphasising the mass of the masonry; this effect is reinforced by suspended niches or isolated recesses containing figurative reliefs. The windows follow Poccianti’s customary preference for thermal types or simple architraved openings decorated only with plain parallelepiped console brackets. The same formal strategies govern the few external portions affected by the project: the bell tower – which rises from a brick base with smooth corner ashlar through a canonical sequence of pilaster orders (allowing the inclusion of Poccianti’s favoured Tuscan order) and terminates in an original pavilion dome – and the short side façades of the nave, which repeat the motif of the free-standing corner column already displayed in Don Giovanni de’ Medici’s elevation. (The question of decorating these lateral entrances would finally be resolved in the 1930s by Luigi Pera.)

Poccianti’s most innovative contribution lay in the decision to convert the existing lateral wings into proper side aisles (each covered with a barrel vault, while the central nave was to receive a new flat ceiling with geometric coffering). This was to be achieved by breaking through the walls and inserting columns with atchitraves, as was done in a classical basilicas. Work on this transformation did indeed begin, only to be abandoned after Leopold II halted the entire renovation in 1857. Above all, as scholarship has recognised, the side aisles would have made manifest the church’s role as a repository of the Order’s memory. That role is iconographically emphasised in the model by the recurring panoply reliefs placed between the windows on the counter-façade and along the bell-tower walls. In the very spatial arrangement – which for these galleries also envisaged independent vestibules, externally marked by fish-scale cupolas – the Pisan church would thus have been explicitly presented as a place dedicated to celebrating the glorious past of the Stephanian knights: at a moment of widespread historicism and the progressive musealisation of Europe’s architectural heritage; yet, ironically, immediately before the Order’s suppression in 1859, which put a definitive end to any ambition for monumental expansion and improvement of the building.

Media gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.