Structural History

late 13th - early 17th century

The original structure of the Tower of Famine was likely modified—at least in part—when it was decided in 1288 to imprison Count Ugolino della Gherardesca. According to the Fragmenta historiae pisanae, following the arrest and detention in chainls of the Count and his family at the Palazzo degli Anziani (also known as the Palazzo del Popolo), twenty days of labour were required ‘until the prison of the Torre dei Gualandi in Piazza delle Sette Vie made ready’ [‘in fine che fu acconcia la pregione della Torre de i Gualandi da sette vie’]. Unfortunately, the historical record does not specify the nature of these alterations, which may have included blocking openings or installing iron grates. Archaeological traces within the tower suggest the presence of a closure system added after its original construction. Small holes in the interior walls and the thresholds of surviving doors and windows point to some form of securing mechanism. However, these features remain difficult to interpret and cannot be dated with certainty.

In 1318, a proposal was made to relocate the prison to an area near the Palazzo del Podestà and the church of San Felice, due to the Tower of Famine’s proximity to the domus of the Anziani, whose meetings risked being overheard. The tower’s effectiveness as a place of detention also appears to have been in doubt, as that same year saw the escape of several Genoese prisoners. Even so, it continued to function as a prison until 1353. Although initially built as a private residence and later partially converted into a prison, the tower seems never to have entirely lost its residential character, as sources from 1322 to 1336 repeatedly refer to it as the dwelling of the Capitano del Popolo.

Between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the Pisan civic government invested in the area by purchasing private residences to house various magistracies; the Palazzo degli Anziani itself eventually took shape through the union of several such structures. Despite these developments, the Tower of Famine never changed ownership and remained part of the Gualandi family’s estate. Records from the early fourteenth century indicate that the city government paid an annual rent of ten lire for its use. This arrangement appears to have remained in place at least until 1428, when the Pisan catasto still lists the tower as being used by the Comune, even though the Capitano di custodia e balia had reportedly failed to pay rent for more than twenty-one years. Nonetheless, the tower was one of the few Gualandi properties still in good condition, unlike their houses in the San Sisto area, which had fallen into ruin.

To trace further developments concerning the Tower of Famine, one must turn to the mid-sixteenth century, when its fate became closely linked to Duke Cosimo de’ Medici’s redevelopment of Piazza dei Cavalieri and the foundation of the Order of Santo Stefano. In 1567, Cosimo granted the Order of Saint Stephen the Palazzo del Capitano del Popolo along with the tower, for the construction of the Order’s infirmary. In the deed of donation, the tower is already described as being in poor condition: ‘The partially ruined tower known as the Tower of Famine’ [‘Turrim semidirutam nuncupatam della Fame’]. Construction and modifications to the two structures continued for some forty years until, under Ferdinando I, they were unified into a new architectural complex—known today as the Palazzo dell’Orologio and referred to at the time as the Palazzotto del Buonomo.

The exact date when the tower was connected to the nearby Palazzo del Capitano del Popolo by a walkway is unclear. However, the structure was certainly in place by 1567, when a kitchen was commissioned there for the church’s prior.

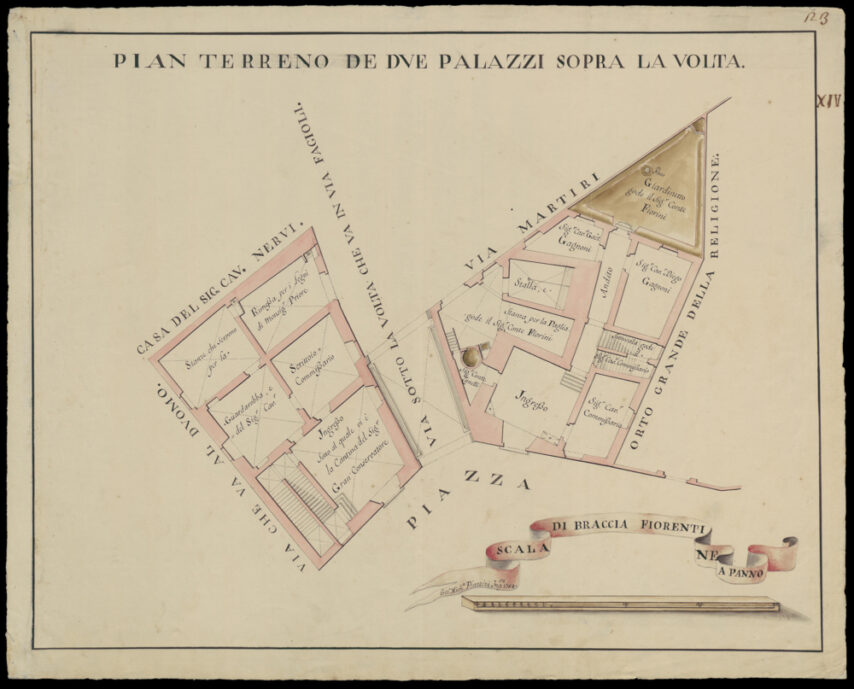

Between 1578 and 1579, construction work continued with the addition of a wooden roof to the Tower of Famine and a service well near its south-west side to serve the Palazzotto, as shown in Giovanni Michele Piazzini’s 1754 plan. By this time, the tower, having lost its original function, was repurposed as a structural framework around which the new construction was adapted. In 1580, a window was created to allow access to the well, possibly corresponding to the opening cut into the southern wall of the tower and framed with a brick cornice.

Around the late sixteenth century, undocumented but still visible modifications were likely made to the northern side of the Tower of Famine, including a ground-floor opening overlooking a stable room built between 1582 and 1583 on the north-west side. The external arches of the first and third-floor openings were reconstructed, and a second-floor opening was probably created anew, each with a segmental arch and double archivolt: the inner layer using bricks laid on edge, the outer layer above laid flat. A similar second floor opening on the southern side, constructed with the same technique, was subsequently sealed.

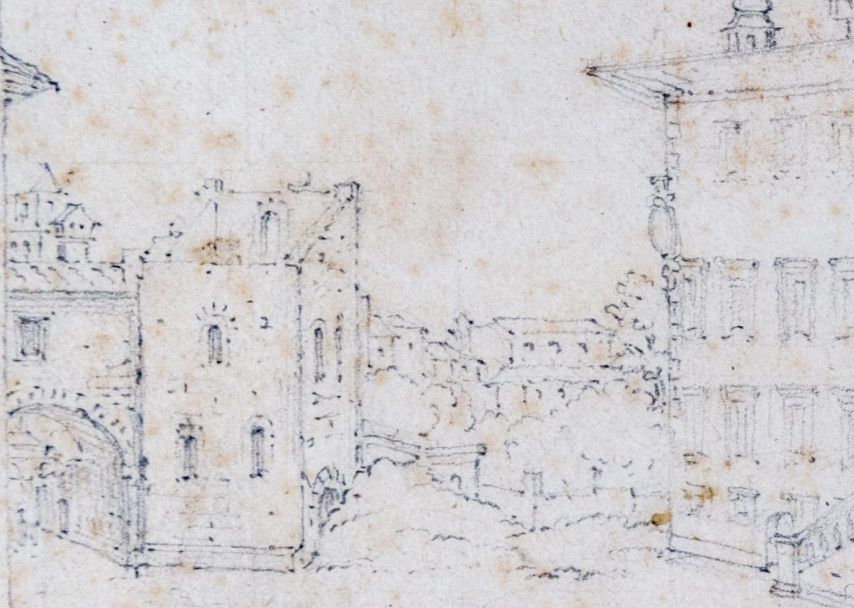

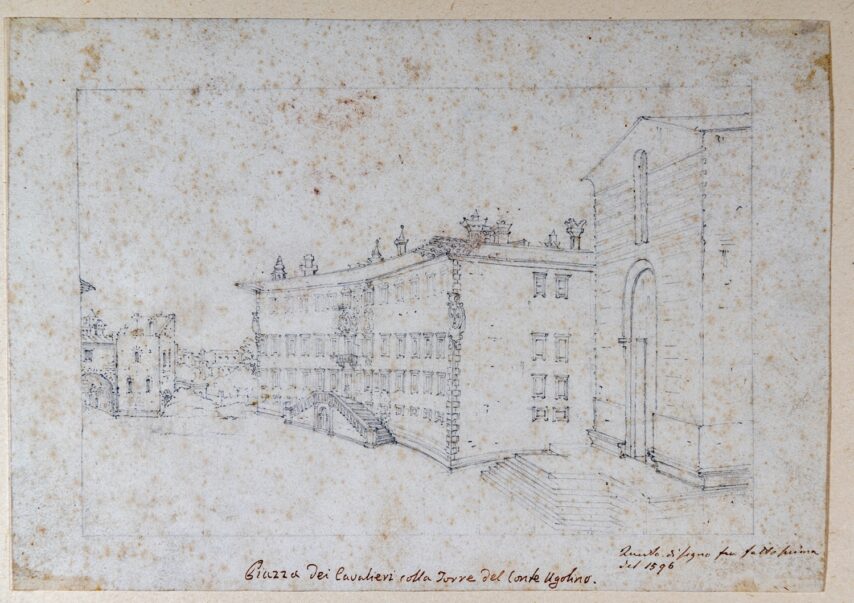

In the years that followed, the Tower of Famine was partially dismantled, most likely along its north-east perimeter, where no trace now remains. Records from 1584 and 1586 note payments to a donkey driver for transporting ‘stones removed from the Tower of Famine’. The dilapidated condition of the structure at that time is further confirmed by a graphic view of Piazza dei Cavalieri dating from before 1590, preserved in a later tracing held at the Palazzo Reale in Pisa. This image represents the last known visual record of the tower before its incorporation into what would become the Palazzo dell’Orologio. Further damage to the medieval remains occurred in 1606 during works to adapt the pre-existing structure to the new building. One corner of the old tower—projecting into the main hall of the adjacent house—was cut back over a length of some three metres: ‘The stones of the main corner of the old tower that projected into the main hall of the house being built next to the small palace, which measured five braccia, where (the stonemason) worked for a day and a quarter, in addition to the extra benefit’ [‘le pietre della cantonata principale della torre vecchia che escivano nella sala principale della casa che si fa acanto il palazzotto, le quali erano b[raccia] cinque, statovi (lo scalpellino) una giornata e un quarto e di vantaggio’]. The visual erasure of the tower from the square was now taking definitive shape.

Palazzo dell’Orologio

Main EntryMedia gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.