Clock

The tradition of the piazza clock is closely tied to the civic dimension of urban life. In Florence, the chime of the public clock — ‘sounding the hours’ [‘suonante le ore’] — incorporated into the bell tower of Palazzo Vecchio, is attested as early as the mid-fourteenth century, but numerous analogous examples exist in Tuscany and beyond, often involving artists of renown. This was the case, for instance, with the ‘clock of Mercato Nuovo’ [‘oriuolo di Mercato Nuovo’] in Florence, an automatic device equipped, as Giorgio Vasari recalls in his Vite (1568), with a striking putto crafted by Andrea del Verrocchio and fitted with ‘loosely jointed arms so that, when raised, he strikes the hours with the hammer he holds in his hand’ [‘braccia schiodate in modo che, alzandole, suona l’ore con un martello che tiene in mano’]. Clocks are also found in the Medici villas, and particular attention to such instruments — whether monumental or collectible — as well as to their maintenance, frequently emerges from the private correspondence of various members of the Florentine dynasty and their associates.

During the works promoted by Cosimo de’ Medici in Piazza dei Cavalieri, it was initially decided to install a clock in the bell tower of Santo Stefano to mark the hours for the entire area. However, it was not until 1678 that one was actually placed on the exterior of the church, with the top of its façade chosen as the location. The arrangement lasted only four years. As evidenced by a 1682 letter from Benedetto Baldinotti, knight and commissioner of the Stephanian convent, who in turn conveyed the opinion of the auditor Ferrante Capponi, it was soon realised that ‘continuing to keep the clock on the façade of this conventual church, where it is presently placed’ [‘continuare a tener l’horiolo nella facciata di questa chiesa conventuale, dove presentemente è collocato’] would pose ‘a constant risk of fire, owing to the need to wind it every evening with a light and carry it above the church’s ceiling’ [‘un risiko continuo di qualche incendio, con l’ocasione [sic] di doversi caricare ogni sera con il lume e portare esso sopra la soffitta di detta chiesa’]. The clock was therefore considered for relocation to the bell tower, reviving Vasari’s original plan, but the greater exposure to the elements and the consequent accumulation of moisture in the new position soon caused the mechanism to malfunction.

The clock thus left Santo Stefano permanently in 1696, to be embedded in the centre of the main façade of the nearby Palazzotto del Buonomo, thereafter, better known as Palazzo dell’Orologio. In the same year, the building’s façade was fitted with the clock face and hand, as well as the marble bell turret, both of which remain visible today. As confirmed by a mid-eighteenth-century plan of the second floor (the present fifth level) of the palazzo, an entire room (‘stanza dell’oriolo’) was provided from the outset to house the mechanism and facilitate winding operations. The clock is still preserved in loco—though no longer functional and stripped of the counterweight system that originally ran within the walls—amid the shelves of the Library of the Scuola Normale Superiore.

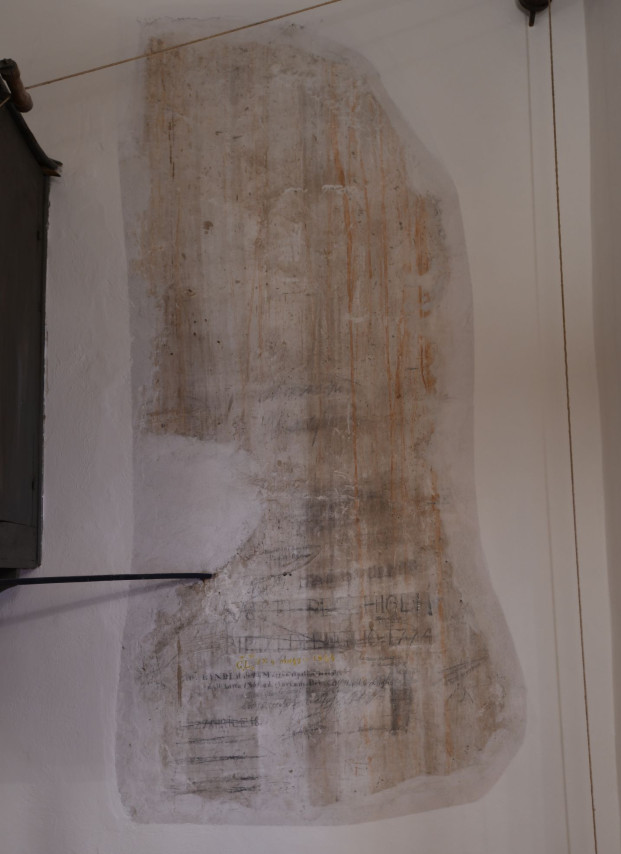

Beside the gears, a fragment of plaster bears annotations in different hands and from different periods relating to the management of the device between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when (as occurred with the plebiscitary elections of 1860 held in Palazzo della Carovana and recalled in a vivid letter by Pasquale Villari) its operation remained essential to the life of the piazza and of the city, making monitoring operations frequent. Although many of the inscriptions are crossed out with superimposed lines or repeatedly erased to make room for later ones, some can still be discerned: ‘[…] Pecchioli repaired it on 11 (?) July; ‘G.L. on 4 May 1844’; ‘Giovanni Landi cleaned and restored it on 13 May […] of the year 1851, to the glory of God’; ‘On 14 [the] 8 [sic] July Vittorio Bertolucci dismantled it and took it away […] year 1883’. [‘[…] Pecchioli rip. 11 (?) de luglio 1774’; ‘G.L. il dì 4 maggio 1844’; ‘Gio. Landi il dì 13 Maggio ripulì, e restau[rò] […] dell’anno 1851 ad gloriam Dei’; ‘Il 14 il 8 [sic] luglio Vittorio Bertolucci losmonto [sic] e l’ho portato via […] anno 1883’].

These annotations are echoed in the twentieth century by documents preserved in the archives of the Pisa and Livorno Superintendency, which record further efforts to safeguard the historic clock and its components. We have no precise information on when its mechanism ceased to function, but a restoration attempt was certainly made in 1969 (shortly before the building passed to the Scuola Normale), when the advice of an expert clockmaker was sought. He provided details on the object’s state of preservation and the interventions required to set it in motion. In particular, it would be necessary to dismantle ‘the entire movement with meticulous inspection of every single component, including thorough cleaning, as it is completely oxidised with deposits dried out from the long period of neglect’ [‘l’intero movimento con scrupolosa revisione di ogni singolo pezzo sottintendendo accurata pulitura, essendo totalmente ossidato con sedimenti essiccati dal lungo periodo di abbandono’].

The specialist continued in his report: ‘It is also necessary to replace the cordage, the current one being deteriorated, and moreover the ropes are unsuitable for such a clock both in length and thickness. Replacement of the metal wire attached to the hammer for the striking mechanism […], reconstruction of the two wooden pulleys attached to the weights indicating the time and the striking. Restabilisation of the striking hammer on the bell, currently damaged from long neglect, and installation of a device […] designed with an oscillating movement for lubricating the escapement wheel, which device is vital to the clock itself’ [‘Occorre altresì sostituire il cordame, essendo l’attuale deteriorato, e poi le corde non consone per tale orologio sia come misura che come spessore. Sostituzione del filo metallico applicato al martello inerente la suoneria […], ricostruzione delle due carrucole di legno applicate ai pesi segnalatori del tempo e della suoneria. Ristabilizzazione del martello battente sulla campana attualmente guasto dal lungo abbandono ed applicazione di un dispositivo […] ideato con movimento oscillante per la lubrificazione della ruota di scappamento, il quale dispositivo è vitalità per l’orologio stesso’].

Today, the clock operates by means of a modern electronic mechanism installed in the 1980s (and recently replaced). Archival records from April 1987 also document work on the hand, which was duly restored and repositioned (these clocks marked only the passing of the hours, so there was a single hand, with one active end and the other serving as a counterbalance).

Palazzo dell’Orologio

Main EntryMedia gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.