Life of the Knights

16th and 17th centuries

At present, no sources are known that document the practical organisation of Palazzo della Carovana, nor do any drawings survive that show the internal arrangement of its rooms. Such evidence would be invaluable for reconstructing the daily life of the knights of the Order of Saint Stephen during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when the Order’s military and naval activity was at its height.

One of the few points that can be established with certainty is the presence of an armoury in the building. Only a few years after the foundation of the Order, in the immediate aftermath of Vasari’s building works, it was probably located in the ground-floor hall corresponding roughly to the present-day Sala della Colonna, although this was not considered an ideal arrangement. In 1582 the Grand Chancellor Fausto Albergotti, acting on behalf of the Dodici (Council of the Twelve), complained that the hall was ‘very damp and exposed to sea winds’ [‘molto umida et sottoposta a venti di mare’], conditions that were detrimental to the state of the weapons and armour, and therefore petitioned Francesco I de’ Medici to authorise their relocation. It remains unknown, however, whether the grand-ducal formal reply—which proposed transferring the collection to what is now the Sala degli Stemmi (‘let it be placed in the hall where arms are exercised’ [‘mettisi nel salone dove si gioca d’arme’])—was ever implemented. What is documented instead are renovation works carried out in 1583 on the medieval hall under the direction of Davide Fortini, probably intended to achieve a more rational organisation of space, since—as Albergotti himself had noted the previous year—‘the said armoury room is full of the said armours, and moreover there are in it many monies paid by those who take the habit to make the said armours’ [‘detta stanza dell’armeria è piena di dette armature, et di più ci sono in essere molti danari pagati da quelli che pigliono l’habito per fare di dette armature’], funds that had probably remained unspent owing to the lack of room.

The reference is to a practice established by the Statutes of the Order, according to which knight-militiamen, ‘at the moment of taking the habit’ [‘nell’atto dell’apprensione dell’abito’], were required to deposit twelve scudi with the general treasurer ‘to purchase a complete corslet armour, surcoat and pike, to be kept in the armoury and used in naval service’ [‘per comprarne un’armadura di corsaletto finita, soppravveste e picca per conservarsi in armeria et usarsi nelle navigazioni’]. Responsibility for safeguarding these armours lay with the convent commissioner, together with the general conservator—one of the twelve knights of the Council—who was required to record their owners in an inventory and by labels affixed to the shelves where they were stored. It was also his duty ‘to have the said armours cleaned, guarded, arranged and kept in order at the expense of the Treasury’ [‘far nettare, custodire, rassettare e mantenere in ordine dette armadure a spese del Tesoro’]. According to later provisions issued by Grand Duke Ferdinando II de’ Medici in 1665, he was furthermore forbidden ‘to lend, give, or deliver any weapon of the armoury and of the Order, except to knight-militiamen who had declared their intention to sail; and to these, only one piece of each type’ [‘prestare, dare o consegnare arme alcuna dell’armeria, e della Religione, se non a cavalieri militi, che si fussero dichiarati di navigare; ed a questi, un pezzo solamente d’ogni sorte’]. If one considers the earliest known plan of the building’s ground floor, that drawn by Giovanni Michele Piazzini in 1754, by the mid eighteenth century the armoury no longer occupied only the Sala della Colonna (which had direct access onto Piazza dei Cavalieri), but also several adjoining rooms, accessible from the upper floors by means of a staircase that no longer survives. The plan, however, reflects a moment of major transition which, under the new Lorraine dynasty, saw the Order gradually transform into an institution devoted to the training of a modern ruling class, with consequences also for the fate of its martial collection. In 1768 the grand-ducal auditor, acting on the wishes of Leopold, ordered the Council of the Order to sell the weapons still kept in the building. About a decade later, this measure was followed by a project to repurpose the area in order to create new quarters, reducing the height of the hall and opening new rooms above it; these would later be transformed into the present-day Aula Bianchi.

Alongside this specific function, the conventual building—the seat of the Order—served in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries primarily as the setting for part of the carovana, a form of training or novitiate lasting at least three years. This institution was not easily defined; it essentially consisted of a period of training or novitiate lasting at least three years. A new knight, who had to be no younger than eighteen, was required to complete it in order to obtain a certificate of seniority and thus become eligible for a senior commandery within the Order. This period of service was made up of several components, which could also be undertaken non-consecutively. These included six months (reducible to two) of religious observance in the church of Santo Stefano—namely attendance at all feast-day services while wearing the habit—as well as service on the Order’s galleys through participation in the annual voyages, including the period of scioverno, or winter lay-up. Obligatory residence in the building also formed part of the requirements, enabling the knight to complete his training. In calculating the three-year total, account could moreover be taken of any missions or appointments carried out on behalf of the Order.

A reading of the Statuti indicates that periods of compulsory residence in the Pisan palazzo formed the core of the cultural and military apprenticeship of new knights. The regulations required them to ‘keep first the mind, and then the body, in motion through exercise’ [‘tenere in moto con l’esercizio prima l’animo, et poi il corpo’]. Intellectual training involved ‘reading histories, understanding the sphere and the navigational chart, and acquiring an introduction to the sciences of cosmography, geometry, arithmetic, and drawing’ [‘leggere Storie, intendere la sfera e carta da navigare, introdursi nelle scienze di Cosmografia, Geometria, Aritmetica e Disegno’], with particular emphasis on military and naval architecture. Physical training, by contrast, focused on skills such as jumping, running, swimming, wrestling, and handling various types of weapons, both edged and firearms. These abilities were developed through tournaments and giochi d’arme, that is, simulated battles fought with real weapons. Such training took place in the present-day Sala degli Stemmi, which is no coincidence: as late as the mid eighteenth century, Giovanni Michele Piazzini still referred to it as the ‘Hall of fencing and other exercises’ [‘Sala della scherma ed altri esercizi’]. The Order also provided further opportunities for physical conditioning and recreation. At the instigation of Ferdinando I de’ Medici, the game of pallacorda was introduced in 1604. Surviving documents confirm that the knights played pallacorda in two structures built behind the garden of Palazzo della Canonica at least until 1762, when the activity was abolished at the request of Monsignor Gaspare Cerati, prior of the conventual church, owing to the disturbance it caused to the resident clergy and the disorder it generated, particularly in the evenings. Finally, a testimony from 1701 records that the carovanisti benefited not only from ‘good masters in the exercise of arms’ [‘buoni maestri nell’esercizio dell’armi’] but also from a dedicated ‘captain’ [‘capitano’], enabling them to handle ‘the musket and the pike’ [‘il moschetto e la picca’] more effectively and to advance in ‘other military practices’ [‘in altre pratiche militari’].

The knights residing in Palazzo della Carovana were required to maintain a cloistered demeanour, characterised by reverence towards God and their superiors. They were expected to ‘conduct themselves in all things modestly, without making any tumult or noise’ [‘portarsi in ogni cosa modestamente, senza far tumulto, o strepito alcuno’]. Each knight was assigned accommodation by the grand prior of the convent and was entitled to board and firewood. They also received a monthly stipend of five scudi, at least from the Addizioni prime (First Additions to the Statutes, 1617) issued under Cosimo II de’ Medici. The Statuti further stipulated that the building was locked in winter ‘at the fifth hour’ [‘alle 5 hore’] (around 22:00) and in summer ‘at the third hour of the night’ [‘alle tre hore della notte’] (around midnight). Knights were, however, permitted to spend up to six nights per month away from the convent, provided they remained within Pisa. All games were forbidden except chess. This conventual and communal spirit was reinforced by the requirement that the knights ‘share the hours of the day’ [‘compartire le hore del giorno’]. They also shared residential quarters, which typically consisted of a bedroom containing one or more beds and a separate study room, both furnished with deliberate sobriety. The Statutes further made provision for cases of incompatibility: if ‘the natures and qualities of the knights did not suit one another’ [‘quando le nature e qualità de’ cavalieri non si confacessero insieme’], the prior could ‘reassign them and provide such companionship as he should judge fitting for peace and unity among them’ [‘mutargli e dar loro quell’accompagnature, che giudicherà a proposito per la pace et unione tra loro’].

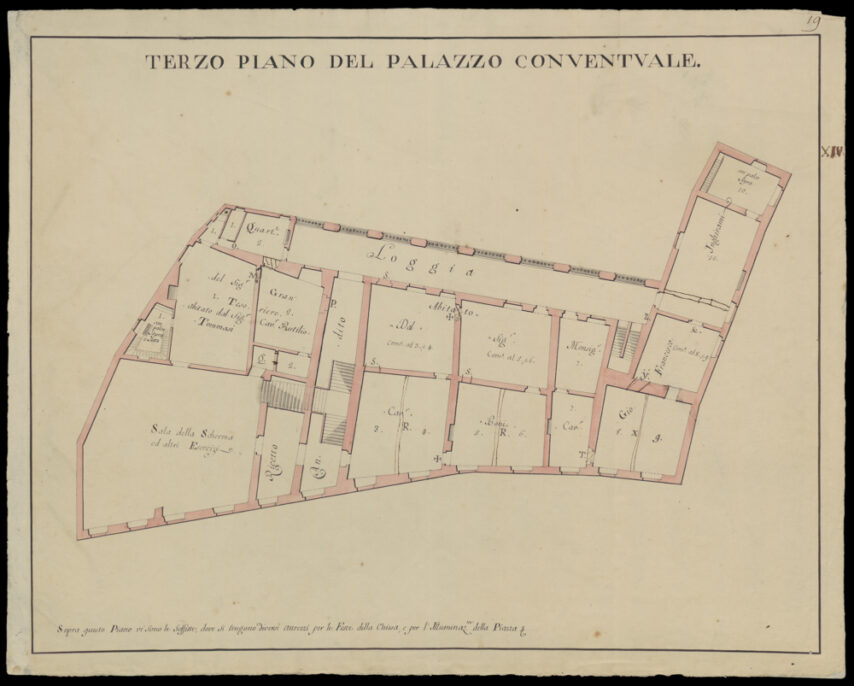

The principal authority governing internal life was the Gran Priore (Grand Prior), a knight elected by the General Chapter and obliged to reside permanently in Palazzo della Carovana. His responsibilities included ensuring ‘that no tumults or noises occur in the said convent’ [‘che in detto convento non si faccino tumulti o romori’] and visiting ‘the knights’ rooms daily to see that life there is conducted in the fear of God and that no evil habits are introduced by those who frequent them’ [‘giornalmente le camere de’ cavalieri per vedere che vi si viva col timore di Dio e non vi s’introduchino da quelli che vi conversano mali costumi’]. In addition to assigning quarters to younger knights, he imposed punishments and, through his assistants, ensured that no one left the building without permission. He also oversaw the prison, which he inspected every two weeks, and shared responsibility for the treasury and archive with their respective appointed officers. The exact location of the detention facility remains uncertain. A testimony from 1777 refers to the ‘antico Quartiere della Botte’—the area now occupied by the Aula Pasquali and the switchboard of the Scuola Normale—as the earlier site of the prison. This space may have been repurposed only shortly before, since a Nota di consegne (an official handover or inventory record) from 1775 records its use as servants’ accommodation. The same 1777 source also notes that a ‘large room next to the fencing hall on the third floor’ [‘camera grande accanto alla sala della scherma al terzo piano’]—the Sala degli Stemmi—was employed for ‘scuole’, that is, for teaching.

In addition to housing the Order’s most senior officers—who, except for the admiral and the constable (both military dignities), were generally obliged to reside in Palazzo della Carovana throughout their term—the palazzo also served as the seat of many of the Order’s institutional functions. For approximately a century—until their relocation in the last quarter of the seventeenth century to the present-day Palazzo dell’Università and Palazzo dei Dodici—the Dodici not only met in what is now known as the Sala del Gran Priore, but the adjoining spaces on the second floor also housed the chancery and the archive. This is evidenced by the devastating fire that broke out there in 1616, destroying part of the documentation. Palazzo della Carovana likewise contained a refectory, in keeping with the traditional cloistered model, where resident knights dined communally, although the cost of board was recorded individually in the Treasury accounts. The Statutiprescribed that ‘when they are in the refectory they shall eat quietly, observe silence, and not rise from the table until one of the chaplains has rendered the due graces to God, at which they must stand and hear them while remaining on their feet’ [‘quando saranno in refettorio mangino quietamente, osservino silenzio, né si levino da tavola prima che da alcuno de’ cappellani non saranno le debite grazie rendute a Dio, alle quali debbono rizzarsi et udirle stando in piè’].Service areas, such as the kitchen, appear in Piazzini’s plan along the edges of the internal courtyard, and there is no reason to assume that the arrangement differed in earlier centuries.

In conclusion, one may ask how many knights lived in the building during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, before Palazzo dei Dodici came into use from the end of the seventeenth century. The residents likely included graduated knights (those holding offices within the Order), conventual knights (already possessing seniority but living there either to take part in naval cruises or while awaiting a commandery), and carovanisti completing their novitiate. On average, between twenty and forty knights probably occupied the building at any one time, with peaks of forty to fifty reached only in the second half of the sixteenth century. This estimate naturally excludes exceptional events that drew large numbers of knights to Pisa, such as major maritime expeditions or public religious ceremonies—for example, the celebration of the victory at Bona in 1609—or the General Chapter. In the latter case, records indicate that 127 knights were present in the convent in April 1571, compared with forty-three in the previous March. For a longer-term perspective, an eighteenth-century account records that twenty-one knights lived in Palazzo della Carovana in 1614, a figure that later rose to thirty-two. When many institutional functions left the building in 1693, freeing up space, twenty-two residential quarters were created; by 1695, these accommodated twenty-four knights. With the turn of the century, however, numbers declined progressively, in part as a result of the reform of 1719, which permitted residence outside the conventual seat. Finally, works initiated in 1751 during the Lorraine reform of the carovana service period led to the creation of twenty-seven quarters within the palazzo. From that point onwards, each was assigned to a single knight, eliminating the possibility of shared accommodation.

Palazzo della Carovana

Main Entry- Preesistenze medievali

- Fasi costruttive

- Functions

- Façade

- Interior

- Varisco, Quadri comunicanti – Jarred

- Aula Bianchi

- La collezione dei calchi epigrafici

- Le opere del Centro Pecci

- Sala della Mensa

- The Coats of Arms of the Knights

- Sala Azzurra

- Sala del Ballatoio

- Sale della Direzione

- Scalone

- Gastini, «… e finire è cominciare»

- Maruscelli (attr.), Figura virile

- Sala degli Stemmi

- Sala della Colonna

- Cortile

Media gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.