Middle Ages

Pisa’s access onto the Tyrrhenian Sea and its control of the nearby inland enabled the city to maintain strategic importance—both militarily and commercially—for centuries. In the early Middle Ages, this translated into a significant degree of autonomy both from the Byzantine Empire (within whose sphere of influence it remained until the early decades of the seventh century) and from the institutions of Lucca, which was the seat of a Lombard duke until the end of the eighth century and subsequently of a Carolingian count, designated as marquis from the mid-ninth century onwards.

Finds dating from the sixth and seventh centuries AD reveal the evolution of the late-antique settlement, which contracted in comparison with the imperial period, ‘taking root in certain areas, particularly those corresponding to the present-day Piazza dei Cavalieri and Piazza del Duomo’ [‘radicandosi in alcune aree, soprattutto quelle corrispondenti all’odierna piazza dei Cavalieri e piazza del Duomo’], as Gabriele Gattiglia writes. During the early medieval period—possibly earlier, but certainly between the seventh and eighth centuries—the urban area that would later coincide with today’s Piazza dei Cavalieri became a productive zone, hosting several metallurgical workshops located between this area and the parallel street to the north, Via Sant’Apollonia. In this phase, the route that corresponds to the present Via Ulisse Dini assumed considerable importance, as did the area around the future church of San Sisto, which has been the subject of recent excavations. The toponym ‘Cortevecchia’, attested from the eleventh century and used, for example, in reference to the small church of San Pietro (documented in 1027 and transformed in the sixteenth century into the present oratory of San Rocco), has enabled scholars to locate the curtis of the Lombard gastaldo in this area. However, the early concentration of settlement in what would become Piazza dei Cavalieri coexisted with extensive ‘semi-rural’ zones immediately to the north, along what is now Via della Faggiola.

In the late Middle Ages, from the end of the tenth century onwards, Pisa experienced rapid and often disorderly growth that only began to assume an organised form two centuries later. This is evidenced by the relocation of ironworking activities from the area of what would become Piazza dei Cavalieri to more peripheral suburban zones. The buildings erected in this period display greater ambition and employ new construction materials. Even private structures began to adopt dimensions previously reserved for public buildings, while the reused materials characteristic of pre-eleventh-century architecture gave way to stone quarried from the nearby limestone deposits of the Monti Pisani and, later (in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries), to brick. Religious construction also expanded during this period, with residential structures clustering around newly founded churches. Near the piazza, the church of San Sebastiano alle Fabbriche maggiori is attested from 1074. Civic architecture, meanwhile, saw the emergence of the tower-house, a symbol of the rising affluent urban elite and an indicator of broadly improved economic conditions.

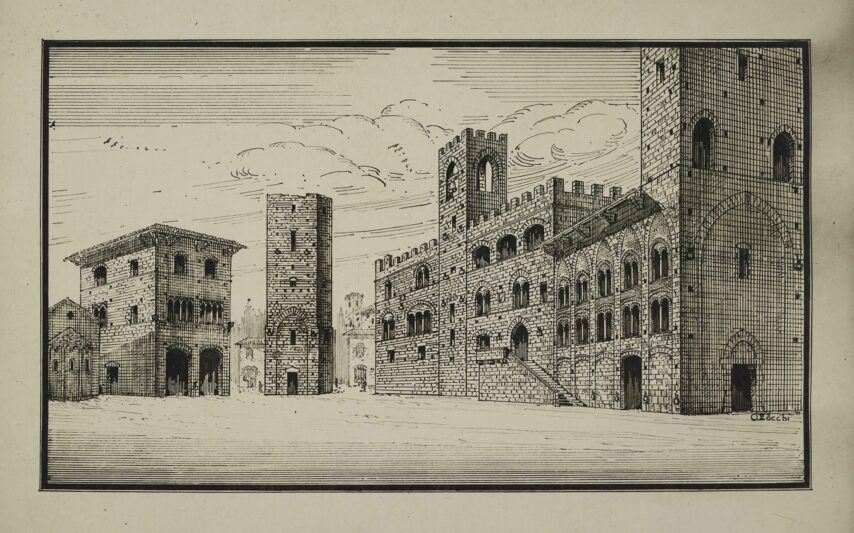

In the late Middle Ages, the emergence of the Commune—dated, based on the earliest references to consuls, to around 1080—with its elaborate institutional network, required a major reconfiguration of the urban layout. After an initial phase of ‘itinerancy’, the official seats were relocated, from the late twelfth century onwards, to a quadrant situated between the area now designated by the toponym ‘delle Sette Vie’ (the former name of Piazza dei Cavalieri) and Piazza Sant’Ambrogio (in the present-day Castelletto district). In the latter were concentrated Palazzo del Podestà (the office itself having been instituted in the final decade of the twelfth century, while the building dates from 1284), the law courts, and the communal chancery. This political-administrative district subsequently expanded to border the area of the ‘Sette Vie’, which from the mid-thirteenth century became the true political centre of the Popolo, housing the seat—initially shared—of the magistracies of the Anziani and the Capitano del Popolo.

Media gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.