Early Modern Period

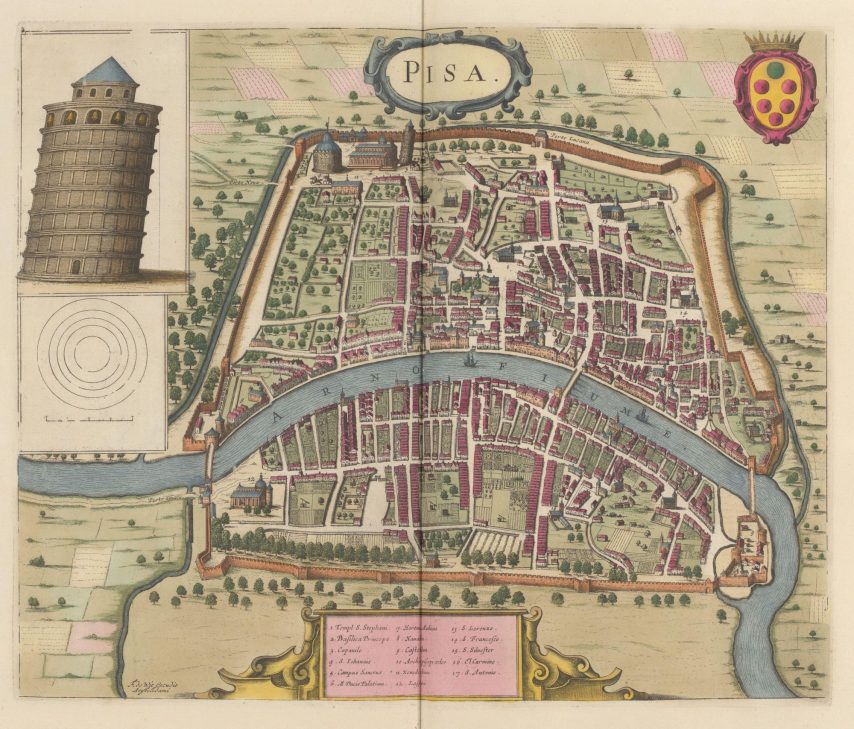

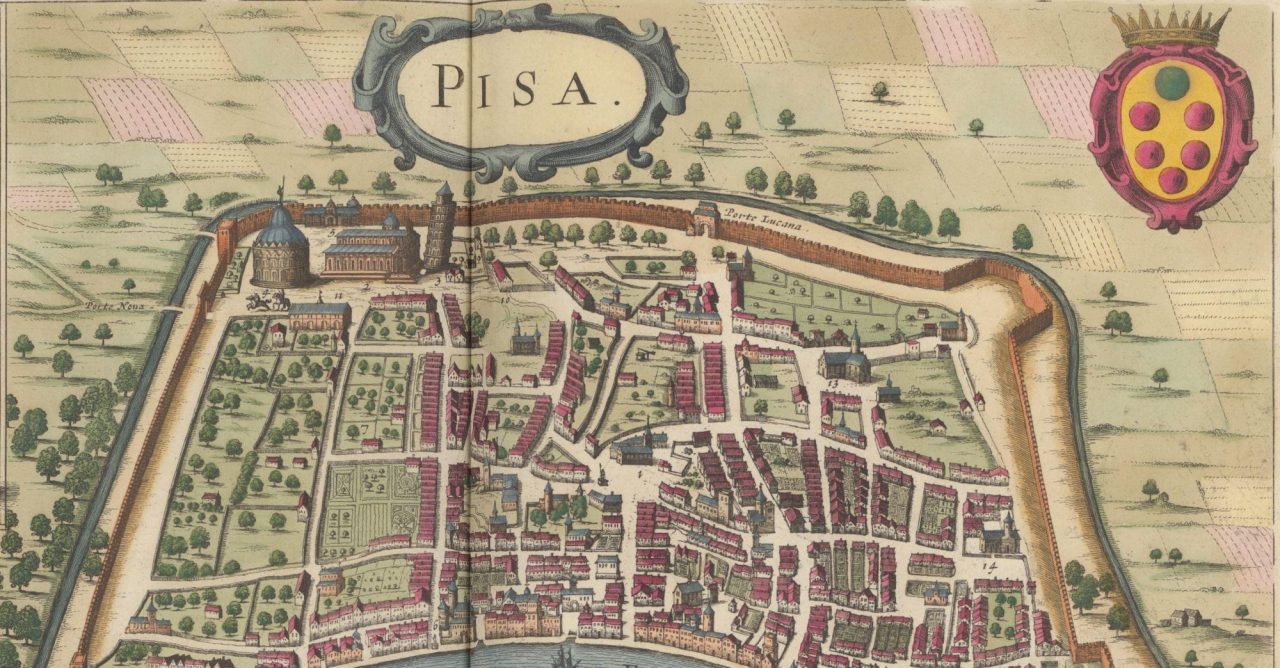

In 1494, at the threshold of the early modern period, Pisa recovered the independence it had forfeited in 1406 as a result of Florentine conquest. The southward advance of Charles VIII of France towards Naples disrupted the delicate balance among the Italian states, inaugurating an era of deep crisis. This brief window, however, proved short-lived: in 1509 Florence regained its former territories, and Pisa—despite a tenacious yet ultimately futile resistance—was compelled to capitulate.This marked the definitive end of its centuries-long tradition of independence. Despite institutional reorganisations of varying scope—following the foundation of the Grand Duchy in 1569 and the subsequent succession of ruling dynasties (the Medici and, later, the House of Lorraine)—Pisa throughout the early modern period formed part of the regional state of Tuscany, centred on Florence.

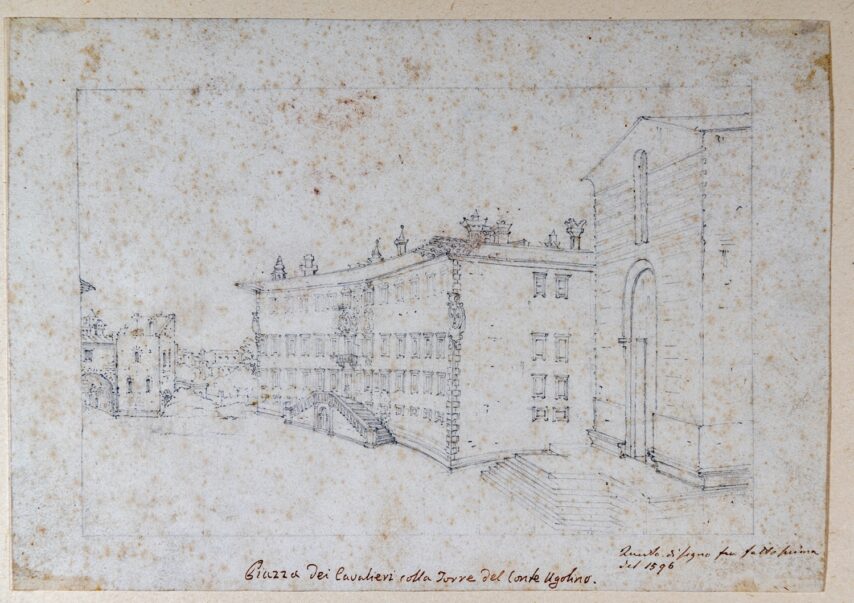

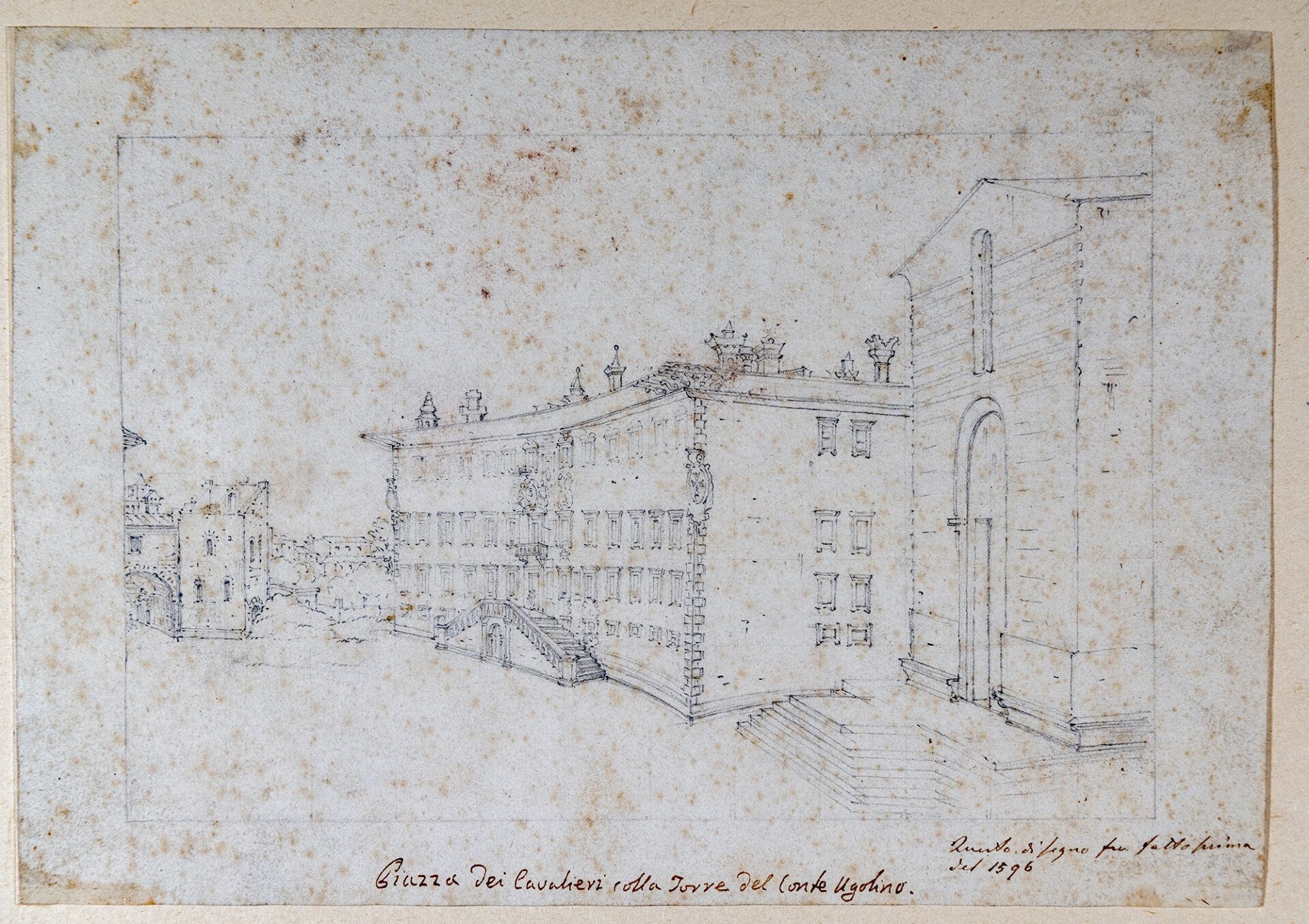

224 x 302 mm

«1. Templ S. Stephani»

Cosimo de’ Medici radically altered the direction of ‘Florentine’ policy, steering it towards the idea of a regional state that would become the backbone of the Grand Duchy’s entire history. Within this framework, Pisa—subjected in the fifteenth century to particularly harsh domination by its conquerors—acquired a new strategic centrality. The (soon to be grand) duke revived the city’s ancient maritime vocation, implemented concrete policies to repopulate both the urban centre and the contado, and reopened and strengthened the longstanding university centre. For the history of the piazza, the impact of his policies was considerable. By ordering the near-total relocation of the city’s political–administrative apparatus, he transformed Piazza del Popolo into the headquarters of the newly founded Order of Saint Stephen, entrusting its redevelopment in 1562 to Giorgio Vasari. Over the course of several years and under three grand dukes, the Piazza’s chaotic medieval fabric was replaced by a homogeneous and orderly scenographic scheme designed to celebrate the unifying, Apollonian power of the Medici dynasty. The success of this undertaking is borne out by the accounts of European visitors, who throughout the early modern period made the Piazza a centre of attraction capable of rivalling the primacy of nearby Piazza del Duomo. From a space of conflict, political deliberation, or everyday urban life, the Piazza now grew increasingly isolated from the city’s usual commercial activity. Yet not entirely: it continued to host religious processions, lavish celebrations of the Order’s military victories, urban games, and the triumphant entries of the grand dukes and their court.

Despite the dynastic change from the Medici to the House of Lorraine in 1737, Pisa maintained a central place in grand-ducal policy. Although the city’s strategic importance declined in favour of Livorno, the standing of its university grew markedly. In this altered context—and following the abolition of the Order’s military role From 1775 onwards, Leopold began transforming Palazzo della Carovana into a centre for the cultural formation of the Tuscan elite. This development, occurring on the threshold of the contemporary period, anticipated the academic vocation that the buildings around the piazza would later assume—a vocation fully realised only from the nineteenth century onwards.

Media gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.