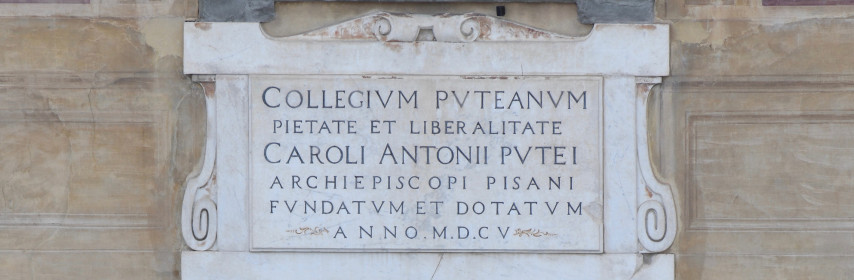

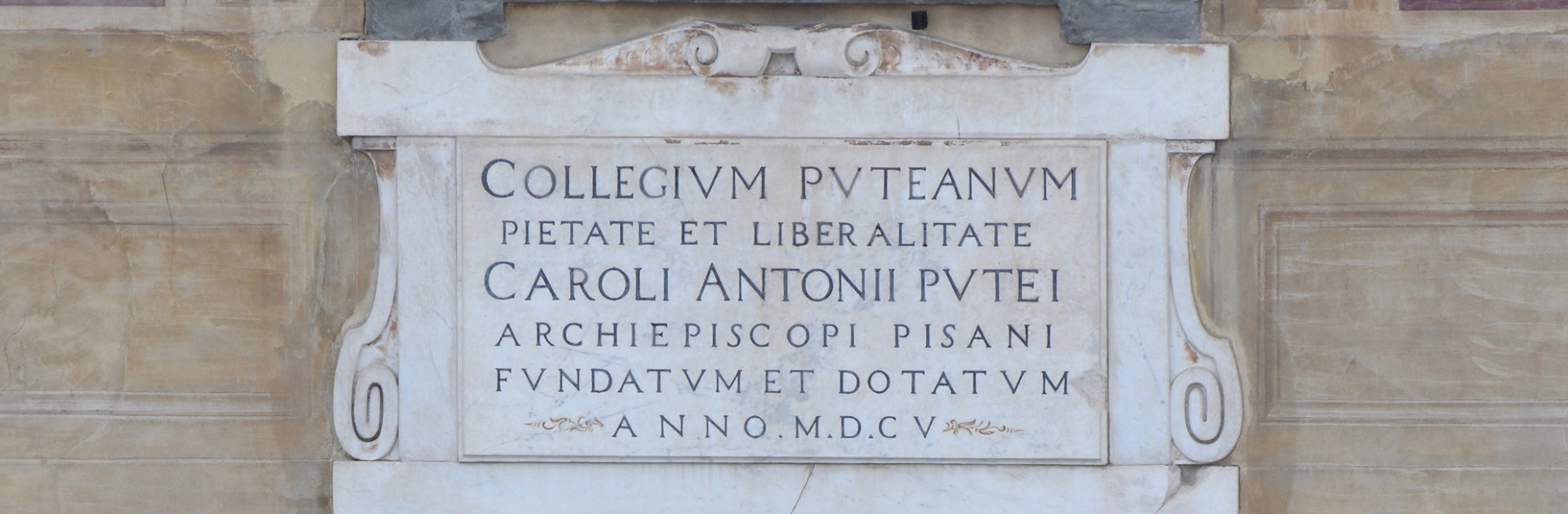

Collegio Puteano

[17th century-present]

With its seat in the building of the same name on Piazza dei Cavalieri—which for centuries served, almost uninterruptedly, as its principal seat—the Collegio Puteano was founded on 8 December 1604 by Carlo Antonio dal Pozzo, Archbishop of Pisa. A native of Biella and a member of the noble family of the Counts of Ponderano, dal Pozzo established the institution at a time when the University of Turin was facing a severe crisis owing to the wars that devastated Piedmont between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The aim of this charitable foundation was to enable seven Piedmontese students from the district of Biella, lacking independent means, to pursue studies in theology, medicine, philosophy, or law at the University of Pisa. The institution received prompt approval from both the Duke of Savoy and the Grand Duke of Tuscany. It was the fourth student college to be established in Pisa between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, following the Collegio della Sapienza (or Collegio di Cosimo, founded in 1542), the Collegio Ricci (established by the archbishop of the same name in 1568), and the Collegio Ferdinando (1593).

According to the statutes laid down by the founder, scholarship holders had to be at least sixteen years old, legitimately born to parents of ‘good repute’ [‘buona fama’], and of such poverty that ‘neither they nor their fathers could support their studies without great inconvenience and a notable burden on their patrimony and household’ [‘che per loro stessi o i padri loro non potessero mantenerli a studio, se non con incommodo grande e aggravio notabile del patrimonio, e famiglia loro’]. They were permitted to attend the Faculties of Theology, Law, Medicine, and Philosophy, and were exempt from the academic fees required for examinations and graduation. Administrative management was entrusted to the Pia Casa della Misericordia, a Pisan charitable institution of medieval origin. Each scholar was entitled to a stipend of 8 scudi, paid by the chamberlain of the charitable body on the 28th of each month, at the close of the month just elapsed. The same statutes drafted by Dal Pozzo state that this provision far exceeded ‘the stipends of the other colleges that are in Pisa’ [‘di lunga mano le provisioni delli altri collegij, che sono in Pisa’]. For this reason, scholars were required to provide independently for their own linen and chamber furnishings, as well as for food and books. The scholarships were funded by an endowment of 73 luoghi del Monte di Firenze (shares in the Monte di Firenze), each valued at seven lire and totalling 7,300 scudi, bequeathed by the founding archbishop. The annual yield from this investment—the effective source of funding—amounted to approximately 698 scudi.

Scholarship holders were appointed whenever a place became vacant, whether through death, graduation, dismissal, or resignation. From among them, a prefect was selected—usually a student of theology—who was responsible for supervising the college. Putean scholars were subject to numerous obligations. Beyond the requirement of rigorously moral and religious conduct, it is noteworthy that, since they were exempt from university matriculation (and the associated fees), they were strictly forbidden to participate in the election of the rector and university councillors—offices held by students under the ancien régime—or to hold such positions themselves, on pain of forfeiting their place. They were also required to recite prayers and psalms for the soul of the founder every Saturday evening, on the anniversary of his death, and daily during Lent. These observances were originally intended to take place in a suspended choir that was to be built in San Rocco but was never realised; this project was instead replaced by the creation of a chapel within the Collegio itself. Conversely, during the ‘general vacations, which are customarily proclaimed from the feast of St John to All Saints’ [‘vacationi generali, che si sogliono publicare da San Giovanni a Ognisanti’], scholars were permitted—so as to escape the Pisan summer heat—‘to absent themselves from Pisa and withdraw to study in cooler places, whether in the hills and countryside of Pisa or elsewhere, provided that they remained in Tuscany, that is, within the territory subject to the Grand Duke’ [‘assentarsi di Pisa e ritirarsi a studiare in luoghi più freschi, o nelle colline et contado di Pisa, o altrove, purché stiano in Toscana, cioè nello stato sottoposto al gran duca’], while continuing to receive their stipend.

The appointment of scholars was a prerogative of the founder’s heirs, the Counts of Ponderano, who held the patronage of the Collegio and exercised this right until the death in 1864 of the archbishop’s last direct heir, Emanuele dal Pozzo. At that point, the right of patronage passed to the indirect descendants, namely the Princes of Savoy–Aosta—Emanuele Filiberto, Vittorio Emanuele, and Luigi Amedeo—sons of Duchess Maria Vittoria dal Pozzo della Cisterna.

Since the prefect was, in theory, a scholar like the others, his term of office lasted six years; once he had graduated and left the Collegio, the princes proceeded to a new election. This practice followed the medieval tradition whereby the supervisor of a community was chosen from among its own members, but it was evident that the mechanism did not ensure effective internal discipline. To remedy this problem, in 1720, with the agreement of the Archbishop of Pisa—who held overall supervision of the Collegio—Prince Dal Pozzo appointed as lifelong rector the priest and former alumnus Giovan Battista Bedotti. Upon his death in 1752, however, the practice of electing the prefect from among the scholars was immediately resumed. Indeed, from that point onward, the choice between an internal prefect and an external rector became a recurring source of conflict between the Archbishop of Pisa and the patron prince, not least because the appointment of an external rector reduced by one the number of places provided for in the statutes. The controversy was resolved only in 1819, when a grand-ducal rescript—reconfirmed in 1843—authorised derogation from Dal Pozzo’s constitutions on this point and mandated the presence of an external rector, usually a Tuscan priest, to oversee the internal life of the Collegio.

Meanwhile, the Napoleonic interlude brought about several significant changes. With the suppression of the luoghi del Monte di Firenze (shares in the Florentine public debt) and their conversion into a fund of 4,977.80 francs, when the Collegio reopened in 1809 after several years of closure, the monthly stipend was set at 10 francs, now paid in advance on the 28th of the month. With the Grand-Ducal Restoration, this sum was converted into 70 Tuscan lire and, later, under the Kingdom of Italy, into 58.80 lire. The Napoleonic abolition of the privilege of taking examinations and graduating free of charge also meant that the Collegio began to reimburse the scholars’ academic fees. In general, the detailed provisions established by the founder remained largely unchanged throughout the nineteenth century, aside from necessary updates introduced with the regulations of 1886. Students were required to sit their examinations and complete their degree by the summer session of the academic year. The monthly allowance was no longer paid directly to the scholar but was administered by the rector to cover expenses for board, personal linen, and cutlery, with any remaining balance handed over to the bursary holder. Meals in the refectory were the same for all and could not be varied, although they were chosen in agreement with the students. Accounts for food and all other outgoings were kept by the rector, assisted by a student—a residual trace of the former ‘student’ prefect—and the rector also oversaw the scholars’ academic progress.

Closed in 1925 owing to a lack of income, the building that had housed the charitable institution for more than three centuries came, barely five years later, to the attention of Giovanni Gentile. Benefiting from the climate of ‘conciliation’ fostered by the Lateran Pacts, the philosopher—appointed royal commissioner of the Scuola Normale Superiore in 1928—opened negotiations from 1929 onwards with Archbishop Pietro Maffi, who by statute exercised supervisory authority over the institution, and with the Pia Casa di Misericordia, then administered by the prefectural commissioner Italo Antonucci. The aim was to secure the transfer of the building to the Scuola Normale, in support of Gentile’s plans to expand both facilities and student numbers. In return, the institution—already transformed under Napoleonic rule—would assume responsibility for funding the seven scholarships for students from Biella, which would thus be reinstated, although their beneficiaries would be housed above San Rocco, thereby reserving the original Puteano building for students of the Scuola Normale. At the same time, in order to comply with Dal Pozzo’s provisions, the agreement also provided for the formal involvement of the Princes of Savoy–Aosta in the appointment of students admitted to the Normale section, albeit on the basis of competitive examination results. In this way, the right of patronage held by the founder’s family (and its successors) in the selection of all scholars admitted to the Collegio Puteano was preserved.

To this day, the Fondazione Collegio Puteano, governed by a Board of Directors, continues to award two annual scholarships to deserving students from the Biella area for study at the University of Pisa. Under an agreement concluded in 1997, these scholars also benefit from the facilities and services of the Scuola Normale Superiore.

Media gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.