Capitano del Popolo

[13th–15th centuries]

The magistracy of the Capitano del Popolo emerged at the end of a long process through which the Pisan Popolo—largely engaged in commerce and artisanal activities—sought representation in city government and a means to make its voice heard.

It was particularly between the third and fourth decades of the thirteenth century that the plenary assembly of citizens (commune colloquium civitatis) gained significant political weight. It worked alongside the podestà in the most important acts of government and expanded to include representatives of the military elite (societas militum), the Guild of Maritime Merchants (Ordine del Mare), and the guild of merchants active on the mainland (Ordine dei Mercanti). The assembly thus came to include twenty-five men from each city quarter (quartiere, the city’s administrative districts). The communitas thus began to assume a pivotal role and, in early 1233, succeeded in having several chapters of its statutes incorporated into the communal statutes. In 1235, the nobility attempted to dismantle this emerging form of government by seeking to restore the consular regime. In 1237, however, nobles and the organs of popular representation reached an agreement that would endure for more than a decade. During these years, a number of new men entered the city Senate, and the concordia ordinum was maintained through support for Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, who favoured Pisa. Over time, the membership of the General Council increased, reaching one hundred representatives per quarter by 1247, for a total of four hundred citizens. Alongside the consuls representing the two major guilds, the consuls of the four minor guilds (leatherworkers, shoemakers, furriers, and smiths) also took their seats. This marked the definitive appearance of the Popolo on the Pisan political stage.

After the death of Frederick II in 1250, internal concord collapsed. Factional struggles resumed among the great noble families—notably the Visconti and the Della Gherardesca, engaged in contesting control of Sardinia—alongside renewed conflicts with other Tuscan cities. Yet in 1254, during negotiations for a peace treaty with Florence—then allied with Lucca and Genoa—the Anziani del Popolo appeared for the first time alongside the podestà. Finally, on 2 December of the same year, the Capitano del Popolo is first documented in the sources: an elected official chosen by the Anziani from a shortlist of three candidates. The relationship between these two magistracies was initially secured, at least in part, through their shared use of a building complex first mentioned in documents of 1261 as ‘palatium Populi de septem viis’, and from 1280 as ‘palatium capitanei et antianorum Pisani Populi‘ (that is, Palazzo degli Anziani). While it is confirmed that, during the early fourteenth century, the Capitano del Popolo was on several occasions—exceptionally—accommodated in the Tower of Famine, recent scholarship has questioned the attribution, from 1327 onwards, of the so-called Palazzo del Capitano del Popolo, overlooking Piazza degli Anziani (later Piazza dei Cavalieri), to this magistracy.

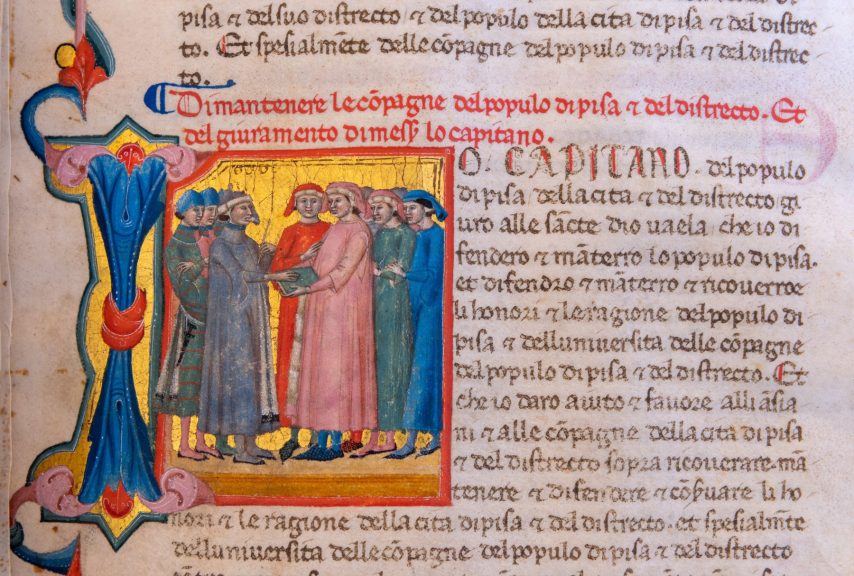

Like the podestà, the Capitano del Popolo was required to be a foreigner. His primary task was to safeguard the interests of the popolani vis-à-vis the nobility, although he did not necessarily belong to the Popolo and could even be selected from among the nobles. This protective role also extended into the judicial sphere, which formally lay within the podestà’s jurisdiction: where irregularities or injustices were identified, the Capitano del Popolo was entitled to order a review of proceedings conducted by the podestà. The Capitano del Popolo was also required to preside over the various councils of city government, particularly those of the Popolo and of the Anziani. In times of war, moreover, he served as the supreme commander of the military forces. Between approximately 1250 and 1270, the growing political weight of the Popolo profoundly reshaped Pisa’s communal institutions. From this period onward, legislative authority was redistributed and entrusted to a bipartite structure: the Council of the Senate and the Council of the Credenza (a restricted executive council), convened by the podestà, were responsible for drafting legislation, while ratification lay with the Council of the Popolo, summoned by the Capitano del Popolo. This system remained in force until 1406, with the beginning of Florentine rule over Pisa.

Although the Capitano del Popolo’s mandate was formally annual and non-renewable, it was not uncommon for the Anziani to grant extended terms, generally in response to periods of crisis or war. Thus, between the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, extraordinary powers combining those of podestà, Capitano del Popolo, and Capitano di guerra were entrusted to Guido da Montefeltro (1289–1292), who held a three-year mandate; to his cousin Galasso, initially appointed for one year and subsequently extended by a further five months (1292–1294); and later to Uguccione della Faggiuola (1313–1316). The possibility of concentrating extensive authority in the hands of a single individual, together with the repeated appointment of certain figures to public office, meant that Pisa experienced repeated episodes of signorial rule over the course of the fourteenth century. These regimes, however, never fully suppressed the authority of the republican institutions. Until 1347, for example, the counts of Donoratico were repeatedly granted extraordinary governing powers, while nonetheless respecting Pisa’s existing political structures. Among them, Gherardo di Bonifazio della Gherardesca served as Capitano del Popolo for several months. Similarly, in the final phase of Pisa’s independence, the signorial power of Pietro Gambacorti and Iacopo d’Appiano was exercised through their assumption of the office of Capitano del Popolo, at times under the exceptional title of Capitano di guerra e difensore del Popolo.

Media gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.