Giovanni Battista Foggini

Saint Stephen Between Religion and Faith

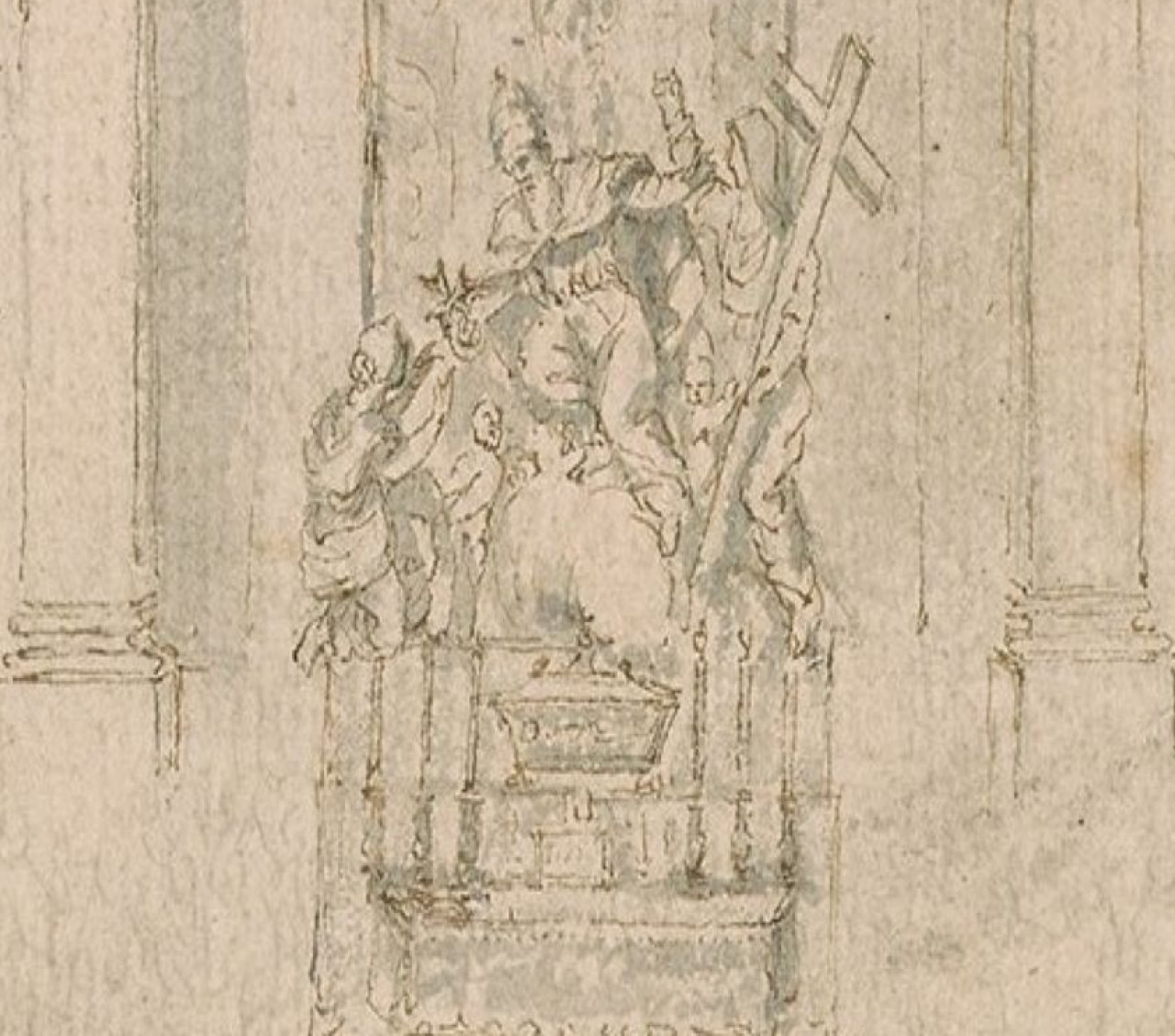

In a side chamber of the conventual church of Santo Stefano in Pisa, adjacent to the presbytery, a monumental sculptural group in gessoed wood, consisting of three principal figures and three putti, all larger than life, is preserved . The work is by Giovanni Battista Foggini, an artist who had already demonstrated the prestige of his art in Piazza dei Cavalieri with the bust of Ferdinando II de’ Medici and would later do so again with that of Cosimo III. At the centre, seated on clouds in pontifical vestments and wearing a tiara, is the Order’s patron saint, Stephen, pope and martyr. In his right hand, he holds the cross of the Knights; his left is extended in a gesture of blessing. To his left stands the allegorical figure of Faith, identified by her traditional attributes of the cross and chalice. To his right, a kneeling figure represents Religion—symbolising the military-religious Order founded by Cosimo de’ Medici. Three putti surround the pope, one of whom bears a sword, evoking both the martyrdom of the saint and the militant vocation of the Knights of St. Stephen. At the base lies a shield emblazoned with the Order’s cross. Long overlooked by scholars, the group was only recently brought to light in a study published in the Annali della Scuola Normale. It predates the completion of Santo Stefano’s high altar by over two decades and was created by Foggini for the translation of the saint’s relics to the Order’s church—an event solemnly marked by a civic procession on 25 April 1683, at the behest of Grand Duke Cosimo III de’ Medici.

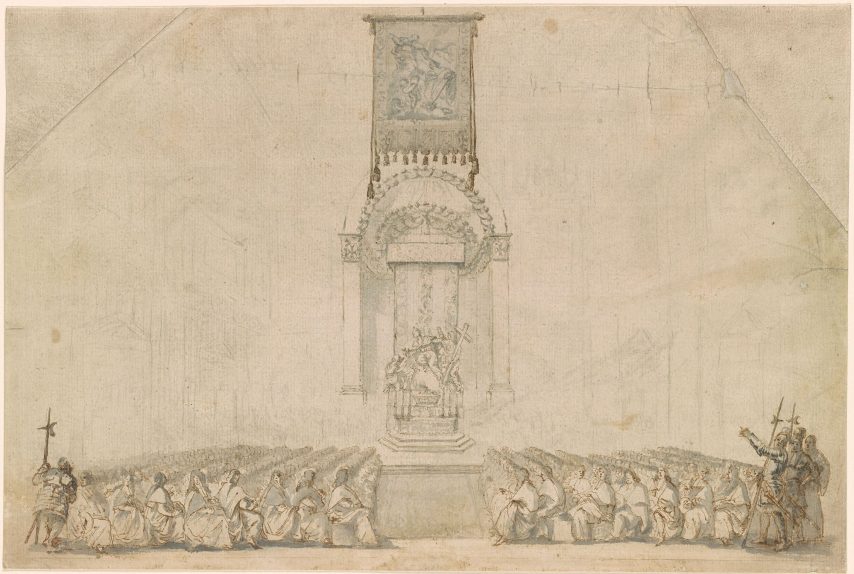

Amid competing proposals from several artists for the permanent decoration of the Stephanian altar, Giovanni Battista Foggini and Pier Francesco Silvani came together in Pisa in mid-September 1682 to devise a new architectural and sculptural scheme. Documented in two drawings now at the Albertina in Vienna, the scheme was to be executed in provisional materials for the upcoming ceremonies, with the hope that the design might later be realised in marble. Barely thirty years old and drawing on his training in the woodworking workshop of his uncle, Jacopo Maria Foggini, Giovanni Battista first produced wax and clay models before carving the final group in various types of Tuscan wood. Among these, the use of gattice—a soft white poplar (Populus alba) that is easy to work but unsuited to a high-quality finish—stands out. Archival documents confirm this choice of material, which reflects both the temporary nature of the work, not intended to last, and the urgency of its execution. A layer of plaster was applied to shape the finer details and imitate the appearance of marble. The project, carried out in Florence with the help of skilled craftsmen, earned Foggini just 300 scudi. Once completed, the group was transported to Pisa and installed a few days before the procession, within a wooden framework designed by Silvani and painted to resemble marble.

https://www.themorgan.org/drawings/item/140946 (attributed to Stefano della Bella)

From the detailed account of the ceremonies by Diacinto Maria Marmi, we learn that ‘the statue of the saint, positioned between Faith and Religion with several putti, sculpted by Giovanni Battista Foggini’ [‘la statua del santo in mezzo alla Fede et alla Religione con alcuni puttini, scultura di Giovanni Battista Foggini’] was ‘universally much praised’ [‘universalmente molto lodata’]. Above it ‘a plain red velvet canopy was raised’ [‘drestava alzato un baldacchino di velluto rosso piano’], while the casket containing the newly translated relics was placed in front. A drawing now in the Morgan Library in New York—attributed either to Stefano della Bella or Domenico Tempesti—confirms Marmi’s account, vividly depicting the ceremony and the sculptural group as it appeared on the altar. Remarkably, the ensemble remained in place for nearly twenty years, until 1701, when work began on a new marble version designed entirely by Foggini.

In 1716, the wooden sculptural group, no longer needed for the decoration of Santo Stefano, was donated to the Pisan church of San Paolo a Ripa d’Arno, where it remained roughly until the mid-nineteenth century. The date of its temporary relocation to a ground-floor room in the Palazzo dei Dodici is unknown, but a 1923 letter from the Provincial Deputation of Pisa to the Superintendent of Monuments recalls its presence there, already outlining plans for its return: ‘the models that served for the group of the high altar of the historic church of the Knights of Santo Stefano—models that would find a more suitable and dignified place in one of the rooms adjoining the church itself. It is therefore also the intention of this provincial administration to carry out the transfer of the aforementioned models from the warehouse where they are currently held to the said church, provided there are no objections from Your Most Illustrious Lordship’ [‘modelli che hanno servito per il gruppo dell’altare maggiore della storica chiesa dei Cavalieri di Santo Stefano, modelli che troverebbero più conveniente e decoroso posto in uno dei locali annessi alla chiesa stessa. È quindi anche intendimento di questa amministrazione provinciale di effettuare il trasferimento dei surrammentati modelli dal magazzino dove trovasi attualmente alla suddetta chiesa quando nulla osti da parte della signoria vostra illustrissima’].

Relocated to the sacristy of the Knights’ church, the sculptural group remains in good condition today. As both a ceremonial installation and a full-scale model intended for later execution in marble, it belongs to a category of temporary sculptural production rarely preserved, making it a work of particular significance in the history of Baroque art.

Media gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.