Iconography

The decoration originally extended across four storeys, alternating landscapes and allegorical figures within a banded scheme featuring war trophies, panoplies, coats of arms and grotesques — elements still visible in the attic of Palazzo dell’Orologio on the front and on the east side.

Starting from the main façade, Piety appears at the top left, depicted in a red-and-white dress, with wings and flames emerging from her head; what appears to be a yellow mantle covers her legs, while in the left corner a cluster of fruits replaces the more familiar cornucopia. In the panel between the first two windows, there was once a landscape, of which only a large rock on the right now survives. Next, between the second window from the left and the clock, is Catholic Faith, shown with a plumed helmet, a white robe and, to her left, the tablets of the Law, as prescribed in Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia (1593–1625); the Perugian writer also assigned her a lit candle and a heart, perhaps now lost, while the angel approaching her remains visible, though truncated by the late seventeenth-century insertion of the clock.

To the right of the clock lies a rocky landscape surmounted by a small fortified structure; on the adjacent peak rises a large leafless shrub, while three small figures cross a wooden bridge below, leading to a cave. The slope continues downward towards a maritime or riverine scene containing buildings, bridges and boats. A relatively recent photograph (perhaps from the early 2000s) preserved in the Pisa Superintendency’s Restoration Archive confirms these details.

After the third window appears Truth, originally identified by the inscription on the cartouche below, still legible in Bellini Pietri’s day (1907). Virtue, bare-breasted, wears a white dress and a broad red mantle; she rests one foot on the globe and holds in her hands a book, a palm branch and a mirror. The figure shows a clear affinity with Prudence, painted by Lorenzo Sabatini in a recess between the Salone dei Duecento and the Salone dei Cinquecento in Palazzo Vecchio (1565): although executed with markedly less skill in the Pisan example, both share the raised right leg and the angle formed by the arm reaching downwards to grasp the book (in one case) or the mirror (in the other). To the right of the last window, another landscape occupies the space, now reduced to a tall leafless tree, though a photograph from the Superintendency — from the same batch as the previous one — also reveals a stretch of city wall.

Turning the right corner of the palazzo, another allegory appears on the upper band, elegantly attired in white and red, adorned with jewels and holding a sceptre — an attribute suggesting that it may represent Justice, Fortitude, or Good Government. Beneath this figure, the most recent restoration uncovered a seated male figure — detached and now preserved in Palazzo della Carovana — who may be identified as Cosimo I de’ Medici. The reasons for the change of plan are unknown, but have been linked to the portrait’s eccentric placement within the iconographic programme and, perhaps, to the intimate tone that characterises it, in direct contrast to the triumphalism of the statue and bust already present at that time in Piazza dei Cavalieri and on the façade of Palazzo della Carovana. The other panels on this elevation — like those along the second register of the front — cannot be interpreted in any meaningful way, though the decorative band in the attic on the east side is particularly well preserved.

Lucia Tongiorgi Tomasi is credited with identifying the allegories on the façade of the palazzo. For most of them, the scholar has proposed an attribution to Giovanni Stefano Maruscelli, to whom a sheet in the Cabinet des dessins of the Louvre (RF 38404, recto) — featuring grotesques and garlands — has been linked in relation to the frescoes in question. The suggestion, put forward by Catherine Monbeig Goguel, does not find exact correspondence in what survives of the decorative scheme that framed the landscapes and allegories, yet a certain affinity is discernible between the grotesque delineated on the sheet and the one in the band surmounting the figure of Truth.

None of the figures mentioned in the report by the mason Paolo Antonio da Lucca — executed partly by Filippo Paladini and partly by Maruscelli — appears, however, to have survived.

The iconography of the vault, painted by Maruscelli alone, is organised according to a geometric grid, yet— as already recognised by scholarship— it is far more airy than that of the façades: the elongated figures are outlined with immediacy and present marked cangiantismo.

Marking the vault at its four corners are the Medici–Stephanian coats of arms. The bands along the long sides alternate garlands and martial emblems, while at the centre, within an architectonic framework, lie landscapes that are difficult to interpret. The one facing the right wing of the palazzo features an ancient tree, with a hill crowned by a building rising behind it, and a traveller in the foreground. The landscape on the opposite side, much more deteriorated, shows a cluster of structures and a foreground figure who may be a peasant making his way to the fields.

Turning instead to the allegorical figures along the shorter sides, those facing Via Dalmazia are almost entirely lost, whereas on the side overlooking Piazza dei Cavalieri only a single figure — Flora — can be discerned. She wears a multicoloured dress, her head crowned with a garland, with shrubs at her feet, and holds a wreath and a basket of flowers in her hands.

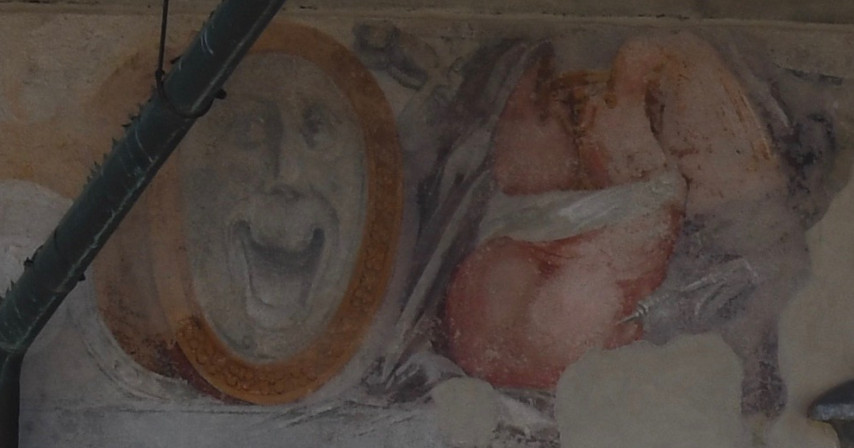

The central field is a profusion of grotesques — a wall decoration of Roman origin rediscovered at the end of the fifteenth century — alternating fanciful vegetal forms, semi-animal and semi-human figures, and masks. Four tabernacles also house four allegorical figures. On the side facing the left wing of the palazzo, Prudence — now almost illegible — and Strength, with a turreted head and a tower as her attribute (following an iconography that diverges from Ripa’s), have been identified; on the opposite side, Justice, holding a flaming bundle, and Temperance, dressed in blue, can be made out. The state of preservation, however, is such that any definitive identification is no longer possible.

Palazzo dell’Orologio

Main EntryMedia gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.