The Piazza and the World: International Voices from the Middle Ages to Today

1387/1400

Geoffrey Chaucer

Off the Erl Hugelyn of Pyze the langour

Ther may no tonge telle for pitee.

But litel out of Pize stant a tour,

In whiche tour in prisoun put was he,

And with hym been his litel children thre,

The eldeste scarsly fyf yeer was of age.

Allas, Fortune, it was greet crueltee

Swiche briddes for to putte in swiche a cage!

[The suffering of Earl Hugelyn [Count Ugolino] of Pisa

No words can fully express, so great was the pity.

But not far from Pisa stands a tower,

Where he was imprisoned,

Along with his three little children—

The eldest barely five years old.

Alas, Fortune! What cruel fate

To trap such innocent birds in such a cage.]

Monk’s Tale (before 1400)

Geoffrey Chaucer (London? 1342/3-London 1400) is unanimously considered to be one of the fathers of English literature. He is the author of seminal texts such as The House of Fame (circa 1380), Troilus and Criseyde (composed in the 1380s), and his celebrated masterwork, The Canterbury Tales (1387-1400), which was written toward the end of his life and survives in an unfinished form. Many aspects of Chaucer’s life remain unknown, and various details concerning his biography are entirely conjectural. Uncertainty exists about the etymology of his name, which, according to some, derives from chaussiere (shoemaker), according to others, from chaucier (maker of breeches).

The reconstruction of his travels on the Continent is also unclear. While some scholars trace his first stay in Italy to 1368 (reconstructed through purely inductive reasoning) to attend the wedding of the Duke of Clarence to the daughter of the Duke of Milan, others place it between December 1372 and May 1373, when Chaucer, entrusted with high-level diplomatic duties, made official visits to Genoa and Florence. A second journey is dated between May and September 1378, when the writer was in Milan to urge Bernabò Visconti and John Hawkwood to support the English war against France.

However, as David Wallace suggests, Italian culture and literature shaped his work well before his direct acquaintance with the Peninsula, such that ‘Chaucer may have heard something about Dante from those many Italian merchants who passed through London, or even from the French lyricists he had imitated and admired since his youth’. This Italian influence stems primarily from matters of language and style. However, broader formal considerations were also at play, particularly in adopting specific narrative structures: the dependence of the House of Fame on the Commedia is well-known, as is that of the Canterbury Tales on the Decameron. In these latter works, specifically in The Monk’s Tale, Chaucer includes the well-known summary of the events of Ugolino della Gherardesca as told by Dante. In this extensive description, the English writer includes a detail absent from Canto XXXIII of the Inferno, placing the Tower of Famine in the Pisan countryside and not, as would be correct, in the heart of the city, in the modern Piazza dei Cavalieri.

As research stands, it is impossible to assert with certainty Chaucer’s presence in Pisa in 1373, although one might hypothesise his passage through the city en route to Florence. The information about the city’s topography could therefore be either the product of imagination, derived from direct observation, or gathered from secondary sources (both written and oral). Regarding the first hypothesis—that the information is a product of imagination—placing a tragic and bloody episode in an isolated location has the power to enhance its sense of disquiet. Mario Curreli, however, argues that Chaucer may have mistaken Ugolino’s Tower for the Torre Guelfa in the Cittadella, having entered the city from the Pisan Port.

Finally, the most intriguing yet entirely conjectural hypothesis is that of a malevolent source. As Wallace suggests, Chaucer’s arrival in Florence in 1373 coincided with the preparations for the lectura Dantis that Boccaccio was to deliver in front of Santo Stefano in October of that year. It is, therefore, likely that Dante and his work were subjects of profound discussion among the literary community to which the English writer belonged. The incorrect information about the tower’s location might have come to him through local sources, perhaps from a townsperson (who had not read Villani’s Nova cronaca). After 85 years, the memory of the events there began to fade.

Alternatively, venturing fully into the realm of playful speculation, we might imagine that Chaucer’s informant was a citizen of Pisa who, in an act of linguistic jest at the expense of a foreign visitor, deliberately confused the infamous Torre della Fame in Piazza degli Anziani with the more rustic and modest—yet phonetically similar—Torre delle Fave, located in the ‘Cappella di S. Apollinare in Barbaricina’, first attested in municipal records of Pisa in 1343.

Beyond the philological reconstruction, however, what remains significant is the novelty of a site that, for the first time, transforms into a genuine literary pilgrimage destination thanks to European literature, even as local memory appears to fade.

1596

Robert Dallington

There are, besides the commodity of the seat, lying betweene Florence and Lyvorno, three other causes, that this cittie is frequented, otherwise it would be very desolate… Another is, for that it is the place where properly the order of S. Stephen is resident, where the Knights of this order have their Pallace, Officers, and other dependances. Not farre from this place is an old ruinous Tower, called by them Torre di fame in memory of the mercylesse crueltie of Ruggiero the Archbishop, who upon suspition of treason immured therein Conte Hugolino a noble Pisano, and his foure children, causing them to be starved: of whom Dante the poet in his 33 chapter dell’Inferno, very elegantly dischourseth, faining, that there for a torment due to such a fact, the Conte lireth upon the Bishopshead with a never satisfied greednesse.

A Survey of the Great Duke State of Tuscany (1596)

Robert Dallington (Geddington, 1561-London, 1637) was an English writer. Born to humble origins in Geddington, Northamptonshire, he attended Benet (now Corpus Christi) College, Cambridge from 1575 to 1580. He became a respected advisor to the royal princes Henry and Charles and authored a collection of elegies and Aphorismes Civill and Military (1613). However, his fame primarily stems from two travel volumes published in 1604 and 1605: The View of Fraunce and A Survey of Tuscany.

Passion for Italy and its culture permeates the writer’s entire career: the Survey was preceded by a partial translation (also to be understood as preparatory for his journey) of one of the most evocative works of the late fifteenth century: Francesco Colonna’s Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (1st original ed. 1499), published with only initials in 1592, while the Aphorismes constitute a florilegium of passages drawn from the works of Francesco Guicciardini.

According to Karl Joseph Höltgen’s interpretation, Dallington is one of the key figures who helped introduce a renewed image of Italian culture to Elizabethan England, thereby expanding its aesthetic horizons and reinforcing connections with continental Europe.

Initially circulating as a manuscript, the volume on Italy recounts Dallington’s 1596 journey as secretary and tutor to Roger Manners, fifth Earl of Rutland. Although relations between James I and the Medici court were excellent (the English sovereign intended to marry his son Henry to the Grand Duke’s daughter) and Dallington’s experience in Tuscany had been entirely positive and satisfactory, the chancery officials of Ferdinando I de’ Medici interpreted the volume as an anti-Medici pamphlet, prompting Ottaviano Lotti, the Grand Ducal resident in London, to request the withdrawal of all copies.

In 1596, when Dallington undertook his journey, the Order of the Knights of Saint Stephen and their headquarters in the Piazza were still a relatively recent addition to the urban landscape. However, the most intriguing aspect of the English writer’s description lies in his special mention of the ‘old ruinous Tower’ – the Tower of Famine – where Ugolino and his sons met their tragic end.

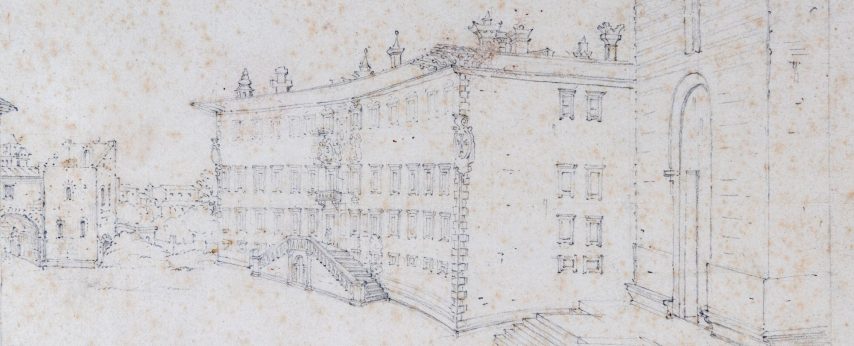

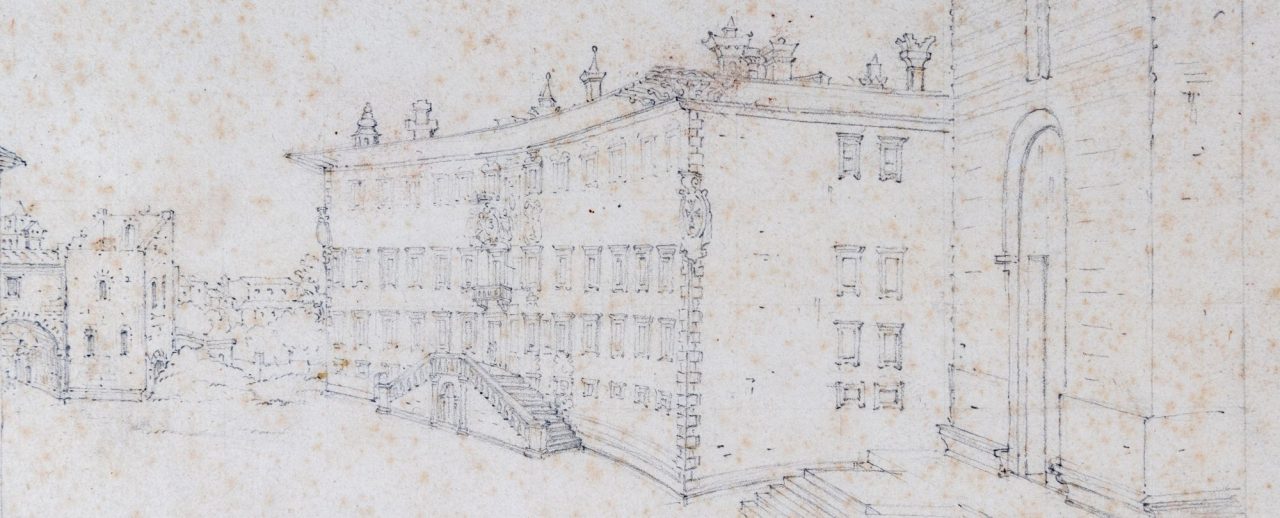

In basso: «Piazza dei Cavalieri colla Torre del conte Ugolino»; in basso a destra: «Questo disegno fu fatto prima del 1596»

Poiché sulla facciata del Palazzo della Carovana non sono presenti i busti dei granduchi, il termine ante quem può essere spostato al 1590, anno in cui venne collocato il ritratto di Cosimo I.

The significance of Dallington’s account lies in its being one of the earliest references to the tower’s fame among foreign visitors, noting that in 1596 it had not yet been incorporated into what would become Palazzo dell’Orologio. Indeed, the renovation works began precisely during the publication of the Survey, lasting from 1605 to 1608. Its ‘ruinous’ profile (which Trifon Gabriele had already noted was in poor condition in a note written half a century earlier) was thus transformed into a pilgrimage site for European literary scholars discovering Dante‘s genius.

Notably, the text associates the structure with the relatively distant Piazza del Duomo rather than the modern Piazza dei Cavalieri. This connection may have been encouraged by the tower’s original orientation. According to available data, its entrance faced away from the piazza, contributing to its isolation from Vasari’s architectural context.

Media gallery

1597

Giovanni Botero

Pisa was once so prosperous that it challenged both Venice and Genoa with substantial naval forces. Its decline began with the devastating defeat of its fleet by the Genoese near the Island of Giglio. This loss left Pisa so weakened that it never recovered its former strength and was forced to submit to Florentine rule. The city's condition worsened dramatically when, during Charles VIII of France's Italian campaign, its citizens rebelled against Florence, only to be subdued again within fifteen years. Many Pisan citizens who could not tolerate Florentine dominion emigrated to Sardinia, Sicily, and other territories. This exodus and the departure of agricultural workers from the surrounding countryside left the low-lying region vulnerable to excessive humidity that made the air unhealthy. Grand Duke Cosimo attempted to revitalise the city by promoting its university, constructing an impressive palace to house the Knights of San Stefano, and offering various privileges to new settlers. However, these efforts to repopulate the city have so far proved unsuccessful.

[Pisa fu già tanto facoltosa che contrastò con grosse armate, e co’ Venetiani, e co’ Genovesi… Rovinò per la strage, e rotta dell’armata loro in un fatto d’arme co’ Genovesi presso l’Isola del Giglio, perché ne restarono tanto debeli che non mai più poterono alzar il capo: anzi furono sforzati a piegar il collo sotto ’l giogo de’ Fiorentini, da quali ribellatisi nella venuta di Carlo VIII re di Francia, et di nuovo soggiogati in quindici anni si disertò la città quasi affatto. Perché i suoi cittadini, impatienti del dominio fiorentino, passarono in Sardegna, in Sicilia et in altri luoghi ad habitare. Così mancando et gli habitanti alla città, e i lavoratori al contado, il paese, che è di sito basso, resta soverchiato dall’humidità che rende l’aria pestilente. Il gran duca Cosmo procurò d’appopolarla co’l favorire lo studio et co’l fabricarvi un bel palazzo per la residenza dei Cavallieri di San Stefano, et co’l concedere diverse esenzioni a gli habitatori, che non vi hanno però fin hora potuto allignare.]

Delle relationi universali (1597)

Giovanni Botero (Bene Vagienna 1544 -Turin 1617) was an Italian writer. He joined the Society of Jesus in 1560 but left in 1580 following prolonged tensions with his superiors. After serving as secretary to Charles Borromeo, he entered the service of Charles Emmanuel I of Savoy before assuming the role of tutor to Federico Borromeo, a position he held until 1598. Returning to the Turin court as tutor to the duke’s children, he also served as a political advisor.

Author of numerous works on moral philosophy, rhetoric, homiletics, and epistolography, as well as writings in the genre of political-military biography, Botero is universally known for his treatise On Reason of State (Della Ragion di Stato, 1598), published by Giolito in Venice. Botero’s entire intellectual output can be traced to a long and articulated polemic with Niccolò Machiavelli (though not without significant borrowings from him). At the heart of the writer’s thought was the need to reconcile state governance and administrative procedures with moral (evangelical) principles, specifically by placing this union under the exclusive aegis of the Catholic Church.

Positioning itself between the thoughts of Machiavelli and Jean Bodin, his work would have broad European influence. However, he diverges from both in the centrality he accords to topics such as economics and demographics – subjects peripheral to the traditional legal primacy (in which he was not peritus [expert]).

In what many consider his magnum opus, published in four parts from 1591 to 1596 (a fifth part only appeared posthumously in 1895), On universal relations (Delle relazioni universali) provided an original and ‘systematic compendium of anthropogeography’ [‘repertorio organico di antropogeografia’] to emphasise the ecumenical centrality of Roman Catholicism. Luigi Firpo noted that it quickly became ‘the definitive geopolitical manual for all of Europe’s ruling class’ [‘il vero e proprio manuale geopolitico di tutta la classe dirigente europea’], enjoying numerous reprints and translations into Latin, Spanish, German, English, and Polish.

In the first part (1591), which includes a compilation of geographical features and human activities across the known world, Botero describes Tuscany with considerable attention given to the city of Pisa. Specifically, the writer reviews the policies that the grand ducal administration had promoted in recent years to revive the fortunes of a town in chronic decline (unusually dating it from the 1241 Battle of Giglio Island against Genoa). Alongside the development of the university centre and the implementation of ad hoc fiscal policies for repopulation, Botero notes the establishment of the Order of Saint Stephen Pope and Martyr and particularly the construction of its prestigious headquarters (‘a fine palace for residence’, today’s Palazzo della Carovana). In a concise yet powerful statement, he highlights a pivotal project where urban redesign and aesthetic beauty combined to breathe new life into the city. The creation (or recreation) of Piazza dei Cavalieri thus became a lesson in good governance that, through the success of the Relazioni, all European administrations would come to learn.

1644

John Evelyn

The palace and church of St. Stephano (where the Order of knighthood called by that name was instituted) drew first our curiosity, the outside thereof being altogether of polish’d marble; within, it is full of tables relating to this Order; over which hang divers banners and pendents, with other trophies taken by them from the Turkes, against whom they are particularly oblig’d to fight; tho’ a religious order, they are permitted to marry. At the front of the palace stands a fountaine, and the statue of the great Duke Cosmo.

Diary (1818)

John Evelyn (Wotton 1620-1706) was an English writer born into a wealthy family of landowners. He studied at London’s Middle Temple and later at Balliol College, Oxford. During the Civil War he sympathised with the Royalist cause although he did not personally engage in the conflict. Between 1643 and 1647, he travelled through Italy and France. In Paris, where the exiled English court resided, he married the daughter of Richard Browne, Charles I’s representative to the French monarch.

In 1659, a year before the end of the civil unrest, he wrote two political pamphlets that earned him Charles II’s esteem. Following the restoration of the monarchy, he held various prestigious administrative positions, serving on numerous commissions (from the Privy Seal to those established for rebuilding St. Paul’s Cathedral in 1666 and caring for the sick and wounded).

A prolific and versatile author, Evelyn wrote works on botany and forestry (Sylva, 1664), treatises on engraving (Sculptura, 1662) and medals (Numismata, 1697), as well as a distinctive work called Fumifugium (1661) about London’s smoke and fog. First published posthumously in 1818, his Diary stands as an extraordinary document of European history, meticulously chronicling over seventy years of events, places, and people in remarkable scope and depth.

After a somewhat unusual route, Evelyn arrived in Pisa on 20 October 1644. Stormy weather had forced him to bypass the port of Livorno, leading to an unplanned landing at Portovenere, from where he made his way overland through Lunigiana. Equally unusual was his first noted site in the city: Piazza dei Cavalieri, rather than Piazza del Duomo, which would have been more expected for a traveller arriving from Viareggio.

Whether this primacy implied an aesthetic preference for the Piazza remains unknown. However, Evelyn’s careful attention to the interior of the church of Santo Stefano is evident. He emphasizes its marble façade, completed only in 1596 to Don Giovanni de’ Medici’s design, and the monochrome canvases depicting the Life of Saint Stephen, conceived by Ridolfo Sirigatti and composed around 1588. The coffered wood ceiling and the pictorial cycle embedded within it date back to the first decades of the seventeenth century. There is some ambiguity in his diary notes: the phrase ‘tables relating to this Order’ seems to refer to the ceiling panels, which focus thematically on the History of the Knights, though the expression ‘over which hang divers banners and pentants’ more plausibly suggests a reference to the wall canvases.

What is certain is that the church Evelyn encountered bore notable differences from the structure we see today. The addition of two lateral wings occurred only between the 1680s and 1690s, while the high altar, designed and executed by Giovanni Battista Foggini, was installed in 1709. Following the addition of the two wings, Piazza dei Cavalieri itself had a markedly different configuration from its current form, as several private structures on the southern side were demolished to accommodate the church’s expansion.

Evelyn’s prioritisation of Piazza dei Cavalieri represents a true unicum among foreign visitors. The grandeur of Medici power might have appealed to the Anglican traveller because of the less ostentatious and more subtle Catholic overtones of the site compared to Piazza del Duomo: a point reinforced by his brief yet revealing observation, which betrays both curiosity and approval regarding the permission granted to the Knights of the Order to marry.

1646-1647

John Raymond

Leaving the area where these things stand together, a little more into the towne is the chappell and Palace, of the Knights of the Or∣der of St. Stephen, the frontespiece of the chappell is of marble neatly pollish’t. The inside is adorn’d with the truest ensignes of valour; I meane trophees taken from the common enemies of christianity, the Turkes. Before their Palace is the statue of the great duke Cosmus, with a fountain. This dignity of knighthood is much like to that of Malta, both to maintain Christs cause against the mahometans, yet these may marrie, the others I conceive may not: These weare a red crosse for their badge in this fashion.

An Itinerary (1648)

John Raymond was an English writer about whom little is known. His life and work are shrouded in obscurity: the date and place of his birth and death are unknown. His only surviving work is a travel guide for English gentlemen, based on his journey through France and Italy in 1646-47. Published in 1648, it appeared under the title An Itinerary, with Il Mercurio Italico as an alternative title on the frontispiece. Accompanied by his uncle, a Royalist exile, Raymond embarked on his tour at a time when England was plunged into civil war. Were it not for differences in route and timing, one might suspect that Raymond travelled in the company of John Evelyn, with whom he shared many observations about the places they visited. In particular, the classic ‘motifs of the contrast between ancient Italy and modern Italy, judgements about Italians’ as well as ‘admiration for the political system of Venice’ are revisited in An Itinerary, as Daniela Giosuè reminds us.

Raymond enters Piazza dei Cavalieri, leaving behind Piazza del Duomo. His assessment, like Evelyn’s, overlooks the decoration of Palazzo della Carovana and focuses on the Church of Santo Stefano: from its marble façade and especially the trophies seized from the Turks and preserved inside, Raymond proceeds to reflections that are more moral than aesthetic. To this seventeenth-century Protestant visitor, the Order of Saint Stephen, with its rituals and institutions echoing those of the older Order of Malta, appeared both as an ethnographic curiosity and a symbol of potential Christian unity—a particularly poignant observation at a time when England was torn by bitter conflicts between Catholic, Anglican, and Presbyterian factions.

1688

François Maximilien Misson

The Knights of Saint Stephen reside in Pisa. As you know, this order is the Order of the Grand Duke, established by Cosimo I in 1561. His statue stands in the Square, facing the Church of the Knights, a church richly adorned with flags, lanterns, and other spoils captured from the Turks.

[Les Chevaliers de S. Estienne ont leur résidence à Pise. Vous sçavez que c’est l’ordre du Grand Duc, et que Cosme premier l’institüa l’an 1561. La statüe de ce Prince est dans la Place, vis-à-vis de l’Eglise des Chevaliers ; et cette Eglise est fort remplie de drapeaux, de fanaux, et d’autres dépoüilles de Turcs.]

Nouveau voyage d’Italie (1691)

When Louis XIV issued the Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685, revoking the freedoms granted to the Huguenots by the Edict of Nantes (1598), François Maximilien Misson, a Protestant counsellor of the Chamber in the Paris Parliament, was forced into exile. Seeking refuge in England, Misson secured a position as tutor to Charles Hamilton, Earl of Arran, accompanying him on an extensive tour across continental Europe between 1687 and 1688. This educational travel, known as ‘The Grand Tour’, had become a well-established custom by then, as scions of British aristocratic families had been encouraged since the early decades of the seventeenth century to undertake educational journeys to the more culturally advanced European societies. Misson’s observations from his travels through Holland, Germany, and Italy were recorded in Nouveau voyage d’Italie (La Haye, 1691), which became one of the eighteenth century’s most widely read travel accounts. Written in an epistolary style, with clear and refined prose, the text established itself as a new model for European travel guides of the eighteenth century.

In May 1688, following visits to Rome and Siena, Misson arrived in Pisa. He described his impression of the city as spectral, vast yet uninhabited: ‘it is a great pity that such a beautiful place should be so poor and depopulated’ [‘c’est grand dommage qu’un si beau lieu soit si pauvre et si dépeuplé’]. This represents a topos noted by numerous travellers, which finds its archetypal expression in Misson’s account. Urban surveys and historical documents substantiate the starkness of this observation.

The city walls erected around 1154 stood out for their extraordinary vastness. This grandeur was justified less by demographic and territorial considerations than by a pure desire for expansion, reflecting the ambitions of the Republic of Pisa, which was then entering a golden period that would last at least until the mid-fourteenth century. However, the first (1406) and especially the second Florentine domination (1509) would provoke a massive diaspora of local noble families who chose voluntary exile. Misson attributes Pisa’s decline to two causes: the final war against Florence in 1509, during which ‘they sacked it and ruined it almost entirely’ [‘ils la saccagerent, & la ruïnerent presque entierement’] and the development of the rival port city of Livorno.

Misson’s reference to Piazza dei Cavalieri must be understood within this context. The Piazza he encountered in 1688 closely resembled its present form, with only minor differences. For instance, the bell tower of Palazzo del Buonomo , now known as Palazzo dell’Orologio, was installed in 1696. Meanwhile, the clock still adorned the church of Santo Stefano, where the expansion of its two lateral wings was nearing completion, finished in 1691. Apart from the Piazza del Duomo complex, this mention of Piazza dei Cavalieri is the sole reference to the city of Pisa in Nouveau voyage. It confirms the success of the Medici‘s symbolic operation in reshaping and partly compensating for the old municipal heritage under the shadow of the six-bezant shield.

1706

De Rogissart

The Prince himself established there an Order of Knighthood, which he named after St. Stephen, whose Chapter meets in Pisa. These Knights must all be of illustrious lineage, and their duty is to fight against the Infidels; indeed, it is said that few cause more harm to the Turks than they do. They wear a red Cross; they are not Ecclesiastics like those of Malta, and they may marry, although most of them abstain from doing so to pursue their duties with greater freedom. The Dukes of Florence had a magnificent Palace built in Pisa for these Knights, with a beautiful Church dedicated to St. Stephen, where they assemble. The portal of this Church is entirely encrusted with marble, and its vault is completely gilded; the interior of the Church is decorated throughout with the Arms of the Knights and the trophies they have won from the Turks

[C’est ce même Prince qui y a institué un Ordre de Chevalerie, qu’il a nommé de S. Etienne, dont le Chapitre se tient à Pise. Ces Chevaliers doivent tous être de famille illustre, & leur emploi est de combattre contre les Infidèles ; aussi diton, qu’il n’y en a guéres qui fassent plus de mal aux Turcs, qu’eux. Ils portent une Croix rouge; ils ne sont point Ecclesiastiques comme ceux de Malthe, & ils peuvent se marier, quoique la plupart d’eux s’en abstiennent, pour vaquer avec plus de liberté à leur emploi. Les Ducs de Florence ont fait bâtir à Pise un magnifique Palais pour ces Chevaliers, avec une belle Eglise dédiée à S. Etienne, où ils s’assemblent. Le portail de cette Eglise est tout incrusté de marbre, & la voûte en est toute dorée; l’Eglise est toute ornée en dedans des Armes des Chevaliers, & des trophées qu’ils ont remportés sur les Turcs.]

Les délices de l'Italie (1706)

Very few biographical details survive about De Rogissart, who authored the popular Délices de l’Italie. Though clearly a French speaker, his first name remains uncertain – scholarly works variously refer to him as Henry or François. Some associate him with Alexandre de Rogissart, a publisher of the same surname who operated in La Haye. The uncertainty is difficult to resolve: his name is never given in full in his only known work (first published in 1706). According to Marina Bailo, he was accompanied on his Italian journey by a certain ‘Mr. H.’, initials usually identified as referring to Abbé Havard, who, however, as evidenced by a passage in the Avertissement of the expanded 1709 edition, only contributed by supplementing or amending various parts of the work.

In his Préface, De Rogissart addresses three types of readers: first, those planning to travel to the Peninsula, for whom he provides a reliable guide to places worth visiting; second, those who have already been there, whose experiences he hopes to revive through his evocative descriptions; and finally, those who, for various reasons, will never be able to witness Italy’s treasures firsthand. These considerations led the author to create an account that extends beyond a mere record of his travel experiences, instead developing into a scholarly work based on extensive research and careful collation of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century sources. Among those he explicitly mentions are Andrea Scoto, whose Itinerarium Italiae he had likely read; Scipione Mazzella, whose Descritione del Regno di Napoli he certainly consulted; and Giulio Cesare Capaccio. This hybrid nature made the work a European bestseller, with Montesquieu himself using it during his Italian journey.

The 1709 text presents descriptions based more on documentary sources and less on direct autoptic evaluations. In accordance with what had by then become a commonplace observation, the author insists on Pisa’s ghostly state— ‘grass grows in the streets’ [‘l’herbe y croit dans les rues’]—depicting a city that had fallen from its medieval heights, though now being revived under Medici rule. He is indebted to Vasari’s Vite for a reference to Nicola Pisano as the architect of the medieval palace later transformed into the Palazzo della Carovana during the sixteenth century—‘the palace of the Knights of Saint Stephen was initially built by Nicola Pisano but was later rebuilt by Giorgio Vasari’ [‘le palais des Chevaliers de Saint Etienne a été bâti d’abord par Nicolas Pisan; mais il a été rebâti depuis par Géorge Vasari’]. Perhaps due to the imprecise city map published in the first edition, he also erroneously places the statua di Cosimo I de’ Medici statue of Cosimo I de’ Medici opposite the Chiesa dei Cavalieri instead of in front of the Knights’ palazzo. However, noteworthy is the rare mention in 1709 of the Palazzo dei Dodici, then the seat of the Order’s Tribunal, which had jurisdiction over crimes committed in the piazza— ‘the Palace of Justice, where the Rota meets’ [‘le Palais de la Justice, où s’assemble la Rotte’].

Some observations that appear only in the 1706 version and were later either deleted or reworked in 1709 seem to align with a firsthand view still clearly imprinted in the writer’s memory. These include the vivid appreciation for the Order’s palazzo (‘un magnifique Palais’), the recollection of the church portal being ‘entirely encrusted with marble’, and the reference to the ‘armes des Chevaliers’ inside Santo Stefano, and not just to the trophies they had won from the Turks. Yet this edition also contains inaccuracies. For example, he praises a supposedly ‘gilded vault’ in the Knights’ church, when in fact it had a wooden istoriato ceiling It is difficult, however, to draw conclusions without knowing when the journey described in the book actually took place: if it occurred close to publication, it would have coincided with the construction of the high altar a project on which even Muslim prisoners were forced to work. This detail finds partial indirect confirmation in the text, where he mentions the high number of slaves in the city, (‘It is also the city… with the most slaves, some of whom are employed in sawing wood, others in carving or polishing marble’ [‘aussi est ce la ville… où il y le plus d’Esclaves, dont les uns sont occupés à scier le bois, les autres à tailler, ou à polir le marbre’]).

1724

Luc-Jean-Joseph van der Vynckt

Having been established by Cosimo I in 1561, Pisa is the residence of the Knights of the military Order of Santo Stefano. Piazza Santo Stefano contains seven or eight palazzi, most of them adorned with frescoes: the largest features a double staircase. The piazza also includes a fountain and a marble statue of Cosimo I, shown wearing the robes of the Order. All the palazzi belong to the Order, and the church is also situated in the piazza. It has a fine façade and, alongside it, a bell tower of equally graceful proportions. Only the central nave is complete, and it is entirely decorated with trophies, standards, and banners taken from the Turks.

[L'ordre militaire de Saint-Étienne aïant été institué par Cosme I en 1561, les chevaliers ont leur résidence à Pise. La place Saint-Étienne a sept à huit palais, la plupart peints en fresques, le plus grand a un double escalier. Sur cette place sont aussi une fontaine et la statue de marbre du dit Cosme I, revêtu des habits de l'Ordre. Tous ces palais sont de l’Ordre ; l'église y tient aussi, elle a une jolie façade et un clocher de même, à côté; la nef du milieu est seulement achevée, elle est toute pleine de trophées, de pavillons et bannières, gagnés sur les Turcs.]

Voyage en Italie de trois gentilshommes flamands (1724-1725)

Luc-Jean-Joseph van der Vynckt (Ghent 1691 – ?1779) was a Belgian writer. Trained as a lawyer, he studied law at the University of Leuven and practised in Mechelen. From 1729, he was a member of the Literary Society of Brussels and the Council of Flanders, and he authored works on Dutch and Flemish regional history. In May 1724, he set out on a European tour with two companions, travelling through France, Germany, and Austria. By October, he had reached Italy, entering via Mont Cenis and travelling down the western coast before ascending the Adriatic side as far as Trentino, then continuing on to Austria. His travel account, preserved in manuscript form by his family, was published posthumously.

Although the text follows the usual pattern of emphasising the former glory of the Pisan Republic in contrast to the city’s modern desolation, it differentiates itself by limiting its description to Piazza del Duomo and Piazza dei Cavalieri, and quoting well-known sources (notably François Maximilien Misson). In addition, the Belgian traveller’s account was one of the first to describe the piazza (which he called ‘place Saint-Étienne’) in all its complexity.

He gave several interesting details: the square consisted of multiple buildings (he hesitated over the total number, likely because it was difficult to treat the structures along the western side of the urban frontage as separate entities), many of which were painted with frescoes (he probably meant the Palazzo dell’Orologio, which was already complete at the time; Palazzo della Carovana—although in fact decorated with the sgraffito technique; and the Collegio Puteano).

He also mentioned the entrance staircase to Palazzo della Carovana (renovated about a century later) and correctly noted the depiction of Cosimo I with the cross of the Knights of Saint Stephen on his armour.

1730

Johann Georg Keyssler

The Knights of St. Stephen owe obedience and military service against the infidels to the Grand Master, who is none other than the Grand Duke of Florence himself. They do not receive a commandery until they have completed their carovane (obligatory three-year training period) ... On official occasions, they wear a gold-bordered octagonal cross of crimson satin on their chest, but outside ceremonies and whenever they appear in public, they display a white satin cross on their cloak...

Their church houses many hundreds of flags and other trophies of victory taken from the unbelievers. The main altar of this church is made of beautiful porphyry and reportedly cost eighty thousand scudi. Above it, Pope Stephen can be seen carved in white marble. The square in front of the church is lined with beautiful buildings, including the Order's palace, around the top of which stand the white marble busts of the Grand Dukes. In front of it stands the white marble statue of Cosimo the Great, which the Order erected in his honour in 1596, ‘Ferdinando Duce et Ordinis Magistro III. feliciter dominante’, as the inscription states.

[[Die Ritter St. Stephani] schweren dem Großmeister, welches kein anderer als der Großherzog von Florenz selbst ist, Gehorsam und Kriegesdienste gegen die Ungläubigen. Sie gelangen auch nicht eher zum Genusse einer Commanderie, bis sie ihre Karavanen vollendet… Wenn sie im Staat sind, tragen sie ein mit Golde bordirtes achteckiges Kreuz von Cramoisi Satin auf der Brust, ausser den Ceremonien aber, und wenn sie sonst ausgehen, siehet man ein Kreuz von weissem Atlas auf dem Mantel…

In ihrer Kirche hängen viele hundert Fahnen und andere den Ungläubigen abgenommene Sieges-Zeichen. Das Hauptaltar dieser Kirche ist von schönem Porphyr, und soll achtzig tausend Scudi gekostet haben. Ueber demselben ist S. Stephanus Papa in weissem Marmor zu sehen. Der Platz vor der Kirche ist mit schönen Häusern bebauet, und auch der Pallast des Ordens darauf befindlich, um welchen oben herum die Brust-Bilder der Großherzoge aus weissem Marmor stehen. Vor demselben ist die Statua Cosmi Magni aus weissem Marmor in Augen schein zu nehmen, die ihm zu Ehren im Jahre 1596 von dem Orden aufgerichtet worden, Ferdinando Duce et Ordinis Magistro III. feliciter dominante, wie die Inscription meldet.]

Neüeste Reise (1740)

Johann Georg Keyssler (Thurnau 1689-Gut Stintenburg 1743) was a German writer and antiquarian. While at the University of Halle, he studied law alongside Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, according to the biographical note in the second edition of his Reisen. In 1713, he began his career as a tutor: first for the Counts of Giech-Buchau, with whom he visited Holland, Germany, and France, and later (1716) for the nephew and children of Baron von Bernstorff, First Minister to His Britannic Majesty. In 1718, he was in England, where he became a member of the Royal Society thanks to his work on the ancient Celtic and Anglo-Saxon cultures (particularly for his essay Exercitatio de dea Nehalennia numine veterum Walachrorum). Accompanying his pupils, Keyssler undertook a Grand Tour between 1729 and 1731, visiting several countries: Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Austria, Hungary, Bohemia, France, England, and finally Holland. He then remained in the service of the Baron’s family, where he was able to work on writing his Neueste Reisen. The work, published in two volumes between 1740 and 1741 (the first containing the account of Pisa), had considerable impact. It was reprinted posthumously (1751) and quickly translated into English (1756-1757), achieving widespread European success. There is evidence that Leopold Mozart, father of the famous composer, owned a copy which he consulted while preparing for his Italian journey.

When Keyssler arrived in Pisa in January 1730, the Order of the Knights of St. Stephen and its headquarters ranked among the city’s greatest attractions, as they did for most visitors in the pre-revolutionary eighteenth century. The myth of Dante, by contrast, had faded into the background, eclipsed in part by the prevailing Baroque taste. In his detailed account, Keyssler shows particular fascination with the daily life of the Knights, vividly describing their customs and ceremonies. From the text, one can even gather that he was aware of the magnificence of their diet, and he refers to their maritime exercises as ‘Caravans’, from which the Palazzo della Carovana still takes its name today. He also explains that the Order’s dedication to Pope Stephen was decided by its founder Cosimo I de Medici because he had won ‘the remarkable victory at Marciano, which effectively established Medici power and rule’ [‘den merkwürdigen Sieg bey Marciano, der eigentlich die Mediceische Macht und Regierung vestgestellet hat’] on the saint’s feast day, 2 August, still celebrated by the Knights.

The cost of the high altar stands among the most significant art-historical details in Keyssler’s account. Erected in the Santo Stefano dei Cavalieri in 1709, just a few years before his visit, it reportedly cost 80,000 scudi. At the time of his stay, only a small number of knights – between ten and fifteen – were residing in the Palazzo della Carovana following the 1719 reform that permitted them to live outside the Order’s headquarters.

1739

Charles de Brosses

The Church of the Knights of St. Stephen, the Grand Duke's order, is entirely decorated with standards captured from the Turks. It's a fine trophy, but I would like to know if some of their own standards might not also be found in mosques. The ceiling is richly gilded and painted by Bronzino who depicted there the life of Ferdinando de' Medici. The high altar in architectural style, made entirely of porphyry inlaid with chalcedony, is a most remarkable piece. In the middle of the square in front of the church stands the statue of Grand Duke Cosimo, founder of the order, with the knights' houses all around.

[L’église des Chevaliers de Saint-Etienne, ordre du Grand-Duc, est toute tapissée d’étendards pris sur les Turcs. C’est un beau trophée, mais je voudrois bien savoir s’il n’y en a pas aussi quelques-uns des leurs dans les mosquées. Le plafond est fort doré et peint par le Bronzino. Il y a représenté la vie de Ferdinand de Médicis. Le maître-autel on architecture, tout de porphyre incrusté de Calcédoine, est une pièce fort remarquable. Au milieu de la place qui est au-devant de l’église, est la statue du grand Côme, fondateur de l’ordre, et tout autour les maisons des chevaliers.]

Lettres familières écrites d'Italie (1739)

Charles de Brosses (Dijon 1709-Paris 1777) was a French writer and politician. After studying with the Jesuits, he was appointed counsellor to the Parliament of Burgundy in 1730, later becoming its president. Though trained in law, his proximity to Parisian Enlightenment circles helped him develop remarkable research abilities across diverse fields of study: from anthropology (Du culte des dieux fétisches, published in 1760, which introduced the concept of ‘fetish’) to archaeology, historiography, linguistics (the Traité de la formation méchanique des langues of 1765 remains a pioneering work to this day), and geography (Histoire des navigations aux terres australes, 1756).

The letters published posthumously in three volumes (1798-1799) as Lettres historiques et critiques sur l’Italie create a misleading impression of immediacy—few were actually written in Italy, with many composed years after De Brosses’s return to France. Unlike typical Grand Tour travellers, his journey to the Peninsula was motivated primarily by research rather than cultural pilgrimage. Specifically, he was gathering material for his magnum opus: the Histoire de la République romaine dans le cours du VIIe siècle, published in 1777, which reconstructed Sallust’s Historiae. While the writing is witty, and the text offers keen observations on local customs, the Lettres contain numerous inaccuracies and gaps, likely because they were written long after the actual visit.

De Brosses describes his arrival in Pisa in a letter to Bernard de Blancey, dated 14 October 1739, titled Route de Florence à Livourne, which places his city stop on the route from the Tuscan capital to the important Tyrrhenian port of Livorno. While the position of Cosimo I’s statue in front of the church might be influenced by De Rogissart’s text, the attribution of the ceiling (more precisely, the six panels placed there) to Bronzino represents a unique claim. Whilst the church does contain a work by the Florentine artist, the Nativity of Christ, it is not a ceiling decoration, but rather an altarpiece. The description of the ceiling’s theme is also incorrect: although Ferdinando I de’ Medici inspired the iconographic programme, the cycle does not actually depict scenes from his life. Also unique is the rich description of the altar, whose design and execution (completed in 1709) are the work of Giovanni Battista Foggini. De Brosses’s wit as an Enlightenment thinker shines through in his irreverent observation about the war trophies on the church walls: he playfully imagines that similar relics, seized from the Knights of the Order of St. Stephen, might be displayed in some Ottoman mosque.

1750

Charles-Nicolas Cochin

In Santo Stefano, there are two paintings that seem to be by Bronzino or from the Florentine school, with some well-drawn pieces. There is also a porphyry altar of good architectural design in a robust style, though its sculptural figures are poor. [...] Throughout the city, several house facades are also decorated in a similarly robust style.

[A S. Stephano, il y a deux tableaux qui paroissent de Bronzino ou de l’école Florentine : il y a des choses bien dessinées. On y voit un autel de porphyre, dont l’architecture est bonne & d’un goûte mâle. Les figures de sculpture sont mauvaises. […] Il y a encore dans cette ville quelques façades de maisons décorées d’un goût assez mâle.]

Voyage d’Italie (1758)

Born into a family of artists in Paris, Charles-Nicolas Cochin (1715-1790) established himself as one of France’s leading engravers. He published his first volume of prints in 1731 at the remarkably young age of sixteen and, by 1739, had secured the prestigious position of designer to the Menus-Plaisirs du Roi (the ‘department’ responsible for organising royal ceremonies). Having entered the entourage of Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson (better known as Madame de Pompadour), he accompanied her brother, the Marquis de Marigny, on a journey to Italy in preparation for the latter’s new role as director of the Bâtiments du roi (the administration overseeing works in French royal residences) upon his return.

The journey, undertaken from 1749 to 1751 in the company of Jean-Bernard, Abbé Le Blanc (writer and historiographer of the Bâtiments du roi) and architect Jacques-Germain Soufflot, proved consequential for Cochin’s development. Beginning with his visit to the recent excavations at Herculaneum, whose importance he fully grasped, Cochin formulated a series of critical proposals for an aesthetic taste that moved beyond the contemporary Rococo fashion. In 1758, Cochin published his account of the journey as a three-volume work, the Voyage d’Italie, which became an essential guide for French travellers in Italy and established a new standard for guidebook writing. Throughout the text, Cochin offers expert observations on the artworks he encountered, evaluating their technique, style, and quality with a critical eye, not shying away at times from negative judgements.

In writing about Piazza dei Cavalieri, Cochin pays particular attention to the interior of the Church of Santo Stefano, and his use of the conditional reveals a connoisseur’s uncertainty: in fact, only one altarpiece is by Bronzino (the Nativity of Christ), while the other (the Lapidation of St. Stephen) is by Giorgio Vasari. His description of the high altar by Giovan Battista Foggini shows the same careful attention to detail, while his comments reveal an early distaste for Baroque sculpture’s excesses – a sentiment that would later align with neoclassical taste. Finally, when Cochin mentions decorated façades, he most probably had the palazzi surrounding Piazza dei Cavalieri in mind, especially its crowning glory, Palazzo della Carovana – though he never names it directly.

1761

Jérôme Richard

The caravans [maritime service] that the knights were required to perform lasted three years; when not at sea, they spent their time in Pisa, living in a large conventual house where each had their own quarters. The Order provided them with wood, candles, and salt for personal use and for their servants, along with a fixed salary for maintenance.

[...]

The piazza in front of the Church of Santo Stefano dei Cavalieri is surrounded by beautiful palaces and adorned with a fountain, above which stands the statue of Grand Duke Cosimo I [de' Medici], the founder of the Order. On the large basin sits the grotesque figure of a sea monster, with human legs, the body and fins of a fish, and a head resembling that of a crab (or sea crayfish), overall of good craftsmanship.

The church's façade is made of marble and was designed by Vasari. The main altar, entirely covered in porphyry, is the work of the Florentine sculptor [Giovanni Battista] Foggini. The church's paintings are mainly from the Florentine school and of fair quality: of particular note is a Nativity of Christ by Bronzino... Attached to the church's frieze are various flags and standards from Turkish galleys captured by the Knights of Saint Stephen.

Les caravanes que doivent faire les chevaliers, sont de trois ans ; ils passent à Pise le temps qu’ils ne sont pas en mer, & habitent dans une grande maison conventuelle, où chacun a son appartement, où la religion lui fournit du bois, de la chandelle & du sel pour son usage & celui de ses domestiques, & une solde fixe pour son entretien. […]

La place qui est devant l’église des chevaliers de saint Etienne, est entournée de beaux bâtiments, & décorée d’une fontaine, au-dessus de laquelle est la statue pédestre du grand-duc Cosme premier, instituteur de l’ordre. Sur le grand bassin est une figure grotesque de monstre marin, qui a les jambes d’un homme, le corps & les nageoires d’un poisson, la tête d’un cancre ou écrevisse de mer, d’un beau travail.

La façade de l’église est revêtue de marbre ; elle a été exécutée sur les desseins du Vasari. Le maître-autel, entièrement revêtu de porphyre, est l’ouvrage du Foggini, sculpteur de Florence. La plupart des tableaux de cette église sont de l’école Florentine, & d’assez bonne main : on y remarquera surtout une Nativité de Jésus-Christ, par le Bronzin… A la frise de l’église sont attachés plusieurs fanaux & étendards des galères turques prises par les chevaliers de saint Etienne.

Description historique et critique de l’Italie (1766)

Jérôme Richard, born in Dijon in 1720, was a French writer and cleric. Much of his biographical information remains uncertain, including the place and date of his death. He served as a canon at the Abbey of Vézelay while holding memberships in both the Academy of his native Dijon and the zoology section of the Institut National. He also worked as a private tutor. In 1761, accompanied by the President of the Parliament of Burgundy Jean-François Charles, he undertook a long journey to Italy, of which he gave a detailed account in his Description historique et critique de l’Italie, ou Nouveaux mémoires sur l’état actuel de son gouvernement, des sciences, des arts, du commerce, de la population et de l’histoire naturelle, published in six volumes in 1766.

The text, which was to have considerable impact, especially for its analysis of the Kingdom of Naples, presents itself as a comprehensive guide – of ‘practical utility’ – introducing not only the artistic beauties of the Peninsula but also providing a deep understanding of Italian reality. In the Avertissement to the first edition, Richard proposes a theoretical exploration of a new approach to travel literature, establishing a sociological investigation ante litteram. His work consists of gathering information from within the ‘cabinet of the minister of state, at the merchant’s counter, and even in the craftsman’s workshop’ [‘cabinet du ministre d’État, dans le comptoir du négociant, & même dans la boutique de l’artisan’] and ‘speaking with the peasant and the shepherd’ [‘parler au cultivateur & au berger’]. Finally, he sets himself the task of comparing this gathered testimony with the actual state of things that he sees and experiences directly.

Richard arrived in Pisa from Empoli. In his extensive historical and urban description of the city, the canon recalls its past greatness, defining it as ‘one of the most powerful cities in Europe’ [‘une des villes les plus puissantes de l’Europe’] and dwells on a meticulous analysis of the structure of the Order, its constitution, as well as the communal life of the Knights of Saint Stephen. His analysis of the Piazza is thorough and authoritative, with particular attention given to the interior of the Order’s church. Richard is one of the few travellers to provide a detailed and original description of the grotesque figure positioned above the fountain basin at the foot of the statue of Cosimo I.

1764

Edward Gibbon

Pisa's continued existence can be attributed to the efforts of [Cosimo I de’ Medici’s] successors who drained the marshes, fostered the University of Pisa's growth, and established the Order of St. Stephen. Nevertheless, I believe that Livorno has undermined Pisa's prosperity.

[C’est aux soins qu’ils ont pris, lui successeurs, de dessécher les marais, de faire fleurir l’université de Pise, et d’y établir l’ordre de St. Etienne qu’il faut attribuer l’existence actuelle de Pise. Je compte cependant que Livourne lui a nui.]

Journey (post 1764)

Edward Gibbon (Putney 1737-London 1794) was an English historian and writer. Known for his monumental work The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire published in six volumes between 1776 and 1789, the scholar represents a transitional figure between the old antiquarian school and the new philosophical approach to history.

In a letter to his father, written from Lausanne on 14 April 1764, Gibbon outlines his planned Italian journey, which was to begin within days: His route would take him from the Moncenisio pass to Turin, then eastward through the Borromean Islands, Milan, Brescia, Padua, and Venice. After a detour to Ferrara, he would turn westward to Bologna and Florence, and from there, to Siena. (‘When we get back to Florence, that place with Leghorn, Pisa, Lucca &c., will furnish us ample matter for between two and three months till the latter of October when we propose going to Rome’).

In his posthumously published autobiography (1799), Gibbon meticulously recalls his long and thorough preparation for the journey, entirely devoted to studying ancient sources, either firsthand or drawn from modern compilers. These sources—including Strabo, Pliny, and Rutilius Namatianus among others—contained extensive references to Pisa. Gibbon entered the Tuscan city on Monday 24 September 1764 and stayed for only one day. In his diary (written in French from 4 August 1761 and remaining unpublished for centuries except for some excerpts published in the Miscellaneous Works of 1796 and 1814), he notes all the Roman remains still present in the municipal territory: from the inscription (whose authenticity he doubted) attributed to Antoninus Pius to the pagan sarcophagi preserved in the Camposanto. This overwhelming focus on classical antiquity overshadowed the medieval and modern aspects of Pisa, which he views through the lens of François Maximilien Misson, borrowing from him a crucial question: Did the Medici and Florentine rule in general benefit or harm Pisa? For the English historian, although the Pisan Republic had flourished in the past, credit must nevertheless be given to Cosimo I and his successors for saving the city from decline. Embodied in the magnificence of its square, the Order of Saint Stephen, despite having abandoned all military operations years before (1719), represented for Gibbon one of the crowning achievements of Pisa’s rebirth.

1791

Friedrich Leopold zu Stolberg-Stolberg

We were eager to visit the 'Torre della Fame' (The Tower of Famine), named for the deaths of Ugolino and his sons; however, not only has the tower vanished without a trace, but there is also debate about its original location.

Wir waren neugierig, la ‘Torre della Fame’ (den Hungerthurm), welcher nach Ugolino’s und seiner Söhne Tod so benannt worden, zu sehen; aber es ist keine Spur von ihm vorhanden, und es wird sogar über den Ort gestritten, wo er gestanden haben soll.

Reise in Deutschland, der Schweiz, Italien und Sizilien (1822)

Friedrich Leopold zu Stolberg-Stolberg (Bramstedt Holstein 1750 – Sondermühlen Osnabrück 1819) was a German poet and writer. He studied law at the University of Halle. As resident minister of the city of Lübeck between 1777 and 1781, he participated in the cultural life of the Göttinger Hainbund, an offshoot of the Sturm und Drang movement, where he aligned himself with the positions of Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi and Johann Gottfried Herder. The author’s production was varied and included poetic works (Gedichte, 1779), theatrical pieces (Apollon’s Hain, 1786), and a seminal utopian novella (Die Insel, 1788). The French Revolution and his Italian travels in 1791-1792 contributed to his controversial conversion to Catholicism, which scandalised German intellectual circles. Having served in prominent diplomatic posts, he retreated from public life to devote himself to historical and religious writing.

Friedrich Leopold describes his visit to Pisa in a letter (number XLIII of his Reise) dated 18 December 1791. Like his contemporary Friedrich von Matthisson, who travelled to Italy in 1795, the German count’s account shares a similar impressionistic style that often reads like a series of vivid sketches. The author’s romantic sensibilities shine through in his detailed attention to nature (especially in his descriptions of landscapes, weather, local plants and crops), folklore (like his mention of the traditional Gioco del Ponte – a ceremonial battle fought on the Ponte di Mezzo), and medieval architecture. When discussing the latter, Friedrich Leopold indulges in some nationalistic pride by perpetuating the mistaken belief that a German architect built the Pisa Cathedral.

This shift in taste completely reshapes how the Pisa and its spaces are seen: beyond the familiar Piazza del Duomo, the new focal points of the city are now the Lungarni (the streets and promenades along the Arno), the noble palazzi along their banks (which the German author, following an old tradition, attributes to Michelangelo), and the Logge dei Banchi. Like the others, the count sees Medici Pisa slip into the background, along with Vasari’s Piazza dei Cavalieri. Yet the square’s presence can still be felt through references to the Tower of Famine and its connection to Dante’s account.

Absorbed into the current Palazzo dell’Orologio between 1605 and 1608, all traces of the ancient structure were lost (at least to non-specialist viewers). Thus, after a little less than two centuries, Grand Duke Ferdinando I de’ Medici‘s wish to make ‘this infamous memory of this truly infamous Tower’ [‘questa memoria infame di questa Torre che è veramente una memoria infame’] disappear was only partially fulfilled: while the building itself became impossible to find, its legend continued to thrive across generations of visitors.

1795

Friedrich von Matthisson

Our gaze reached…all the way to the Baths of Pisa, at the foot of the mountain range about which the venerable Dante says ‘that it prevents the Pisans from seeing Lucca’ [per che i Pisan veder Lucca non ponno]. Not even the slightest trace remains of Ugolino's site of most terrible catastrophic fate, immortalised by Dante, Gerstenberg and Reynolds - I mean the notorious Torre della Fame. No one knows where the fateful prison key fell into the Arno.

[Unser Auge trug… bis zu den Pisanischen Bädern, am Fusse der Gebirgshöhe, von welcher der ehrwürdige Dante sagt, «dass die Pisaner dadurch verhindert werden, Lucca zu sehen». Von Ugolinos, durch Dante, Gerstenberg und Reynolds, verewigtem Lokal der schrecklichsten Schicksalskatastrophe, ich meine den berüchtigten Hungerthurm, wird auch nicht die kleinste Spur mehr angetroffen. Kein Sterblicher weiss anzugeben, an welcher Stelle der verhängnissvolle Kerkerschlüssel in den Arno fiel.]

Fragmente aus Tagebüchern und Briefen (1814)

Friedrich von Matthisson (Hohendodeleben 1761-Wörlitz 1831) was a German writer and poet. After completing his education at the University of Halle in philosophy and theology, he taught at the Philanthropin in Dessau. Following this, he spent several years as a private tutor, moving between different employers. From 1794 to 1811, he served as reader to Princess Luise von Anhalt-Dessau. Due to the Princess’s poor health, which required her to spend time in milder climates, Matthisson was able to make several extended visits to Italy. He passed through Pisa in November 1795 en route to Rome. Following the Princess’s death, he settled in Stuttgart, taking up positions as theatre director and librarian until 1828. As a Romantic poet, his Lieder earned the admiration of Friedrich Schiller and Christoph Martin Wieland, while his Italian travels inspired his Reisebilder. One of his texts, Adelaide, was set to music by Ludwig van Beethoven. Despite the extent of his legacy (his complete works, printed in Zurich between 1825 and 1829, comprise eight volumes), his literary output was quickly classified as derivative.

The author’s notes on Pisa reveal pre-Romantic sensibilities through several key elements: vivid naturalistic impressionism, numerous hyperbolic similes drawing on classical comparisons (likening Pisa to Carthage and Corinth), and most prominently, a marked preference for a stylised Middle Ages, featuring both a highly aestheticised version of Catholicism (focused on ceremonies and rituals) and elements of the horrific. In such a climate, there is no longer room for the late sixteenth-century splendour of Piazza dei Cavalieri and its scenographic apparatus serving Medici politics. For visitors from outside, what changes is thus the perception of urban space and how it is hierarchised: Medieval, Republican Pisa takes centre stage, while the Florentine heritage of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries fades to the margins. While Cosimo I‘s piazza loses its centrality, Dante’s memory and its vestiges gain prominence, mainly through the Tower of Famine and the episode narrated in Inferno, XXXIII. Although the reference to the key might allude to a direct reading of Villani’s Nova cronica, the story of Ugolino della Gherardesca becomes central mainly through modern interpretations , both pictorial (Joshua Reynolds, Count Ugolino and his Children in the Dungeon, ca. 1773, Knole House, Kent) and theatrical (Heinrich Wilhelm von Gerstenberg, Ugolino, 1768).

1799

Ernst Moritz Arndt

Piazza Santo Stefano e i suoi dintorni

Questa piazza viene sempre citata, probabilmente perché è l’unica a Pisa oltre alla bellissima Piazza del Duomo, ma è molto irregolare e piccola. È chiamata anche la Piazza de’ Cavalieri, dai Cavalieri di Santo Stefano. Quest’ordine cavalleresco è stato istituito da Cosimo I [de’ Medici] per combattere gli infedeli ed è diventato subito straordinariamente ricco e potente grazie alle sue donazioni e dotazioni, continuate con i signori successivi. L’Ordine interveniva con numerose galere e fregate contro gli infedeli e serviva per tenere libero il Mediterraneo. Con Leopoldo [Pietro Leopoldo I di Toscana] queste crociate sono cessate, ma non l’Ordine.

Qui si può vedere anche il Palazzo dei Cavalieri, un edificio molto maestoso, ornato da sei busti dei principi medicei e dei loro antenati, esposti entro piccole nicchie sopra il primo piano. Anche all’interno si può ammirare qualche cosa curiosa, ritratti e alcuni dipinti. Di fronte al palazzo si trova la statua di Cosimo, il fondatore di quest’ordine, eretta dai Cavalieri per riconoscenza sotto Ferdinando II [sic], come recita l’iscrizione. Non ha nulla di eccellente, non più della fontana che dovrebbe abbellire la piazza.

I Cavalieri hanno anche una chiesa proprio accanto al palazzo, con una facciata gradevole. Ha una sola navata e nulla di grandioso; le decorazioni e i dipinti all'interno sono di qualità mediocre e la maggior parte delle bandiere e delle insegne turche e barbaresche che vi erano appese sono state tolte, dato che l’Ordine non ha più una sola galera in mare e il suo arsenale sull’Arno è vuoto. Di fronte al palazzo si trova il Collegium Puteanum e un altro collegio, dove si insegna diritto feudale, destinato forse anch’esso a finire presto tra le antiche rarità.

La cosa più curiosa, in questa zona urbana, sono i resti della famosa Torre della Fame, che riveste una così grande importanza nella 'Divina Commedia' di Dante. Ugolino della Gherardesca (famiglia che tuttora esiste a Pisa) fu sospettato di tradimento, con l’accusa di aver consegnato la patria al nemico e di volerne diventare il capo. Questi eventi vengono a cadere nell’anno 1282, periodo in cui i pisani erano stati così sfortunati nelle battaglie contro Genova e Ugolino era il capo dei guelfi, che in quel momento avevano il sopravvento. Ma vinsero i ghibellini, egli fu imprigionato in una torre insieme ai suoi figli, e con loro morì di fame in modo atroce.

Ho udito spesso dai viaggiatori e ho spesso trovato scritto che questa Torre della Fame, come viene chiamata da Dante, ancora esiste e alcuni la collocano audacemente sull’Arno, dove non esiste traccia di alcuna torre. Addirittura qui a Pisa questa torre, ovvero questo rudere, viene chiamato la Torre d’Ugolino, ma chi è ben informato e conosce qualcosa di più della storia di quei tempi bui, la colloca unanimemente in Piazza dei Cavalieri. In un piccolo giardino, a fianco del Palazzo dei Cavalieri, si trova un’antica struttura in muratura, che ora confina con altre abitazioni e mura, è provvista in basso di una orrenda inferriata, e si inabissa in terra con le sue possenti strutture; i rami di un pesco in fiore si protendono verso l’alto, accanto a lei. Molti la considerano l'ultimo resto di quella torre dell’orrore e di certo ne ha l’aspetto; né le sue pietre grigie, ricoperte di muschio ne contraddicono la fama. La vidi con sgomento e, pensando al diabolico banchetto di Ugolino, sono proseguito oltre.

Der Stephansplatz und seine Anhängsel.

Dieses Platzes erwähnt man immer, wahrscheinlich, weil er nach dem schönen Domplatz der einzige in Pisa ist, aber er ist ein sehr unregelmäßiger und kleiner. Er heißt auch la piazza de’ Cavalieri, der Ritterplatz, von den St. Stephansrittern. Dieser Ritterorden ward von Kosmus dem Ersten gegen die Ungläubingen gestiftet und durch Schenkungen und Stiftungen unter ihm und den folgenden Herren bald ausserordentlich reich und mächtig. Er zog mit mehreren Galeeren und Fregatten gegen die Ungläubigen aus und diente, das Mittelmeer rein zu halten. Seit Leopold aber haben diese Kreuzzüge aufgehört, nicht aber der Orden.

Hier sieht man auch den Pallast der Ritter, ein ganz stattliches Gebäude, welches sechs Büsten der mediceischen Fürsten und ihrer Ahnen schmücken, die über dem ersten Stock in kleinen Nischen prangen. Auch im Innern sind manche Schnurrigkeiten, Porträts und einige Gemählde zu sehen. Vor dem Pallaste steht die Statue Cosmus, des Stifters dieses Ordens, von den Rittern aus Dankbarkeit unter Ferdinand dem Zweiten gesetzt, wie die Inschrift sagt. Es ist nichts Vorzügliches, so wenig als der Springbrunnen, der den Platz zieren soll.

Auch eine Kirche haben die Ritter gleich am Pallaste mi einer zierlichen Facciata. Sie hat nur ein Schiff und nichts Großes und die Verzierungen und Gemählde drinnen sind auch nur von der mittelmässigen Ort, und was sonst von türkischen und barbarischen Fahnen und Insignien dort aufgehängt war, ist auch meist weggenommen, da der Orden keine einzige Galeere mehr in See hat und sein Arsenal am Arno leer steht. Dem Pallaste gegenüber ist das Collegium puteanum und ein anderes, wo das Lehnrecht gelesen wird, das vieleicht auch bald zu den alten Raritäten gehören wird.

Aber das Merkwürdigste in dieser Region sind die Ueberbleibsel des berühmten Hungerthurms, der in Dantes göttlicher Komödie eine so große Rolle spielt. Ugolino della Gherardesca (eine Familie, die bis heute in Pisa existirt) kam in Verdacht, sein Vaterland an die Feinde verrathen zu haben und sich zu seinem Haupte aufwerfen zu wollen. Diese Zeit fällt in die Epoche, als die Pisaner in den Seeschlachten gegen Genua so unglücklich waren, ins Jahr 1282, und Ugolino war das Haupt der Welfen, die nun triumphirten. Doch siegten die Ghibellinen, er ward mit seinen Söhnen in einen Thurm geworfen und starb mit ihnen den gräßlichen Hungertod.

Ich habe bei Reisenden und in andern Schriften oft gefunden, daß dieser Hungerthurm, wie er von ihm heißt, noch stehe, und einige setzen ihr ganz kühn an den Arno, wo doch keine Spur von einem Thurm ist. Ja hier in Pisa selbst nennt man diesen und jenen Thurm oder Gemäuer la Torre d’Ugolino; aber die Unterrichteten und die von der Geschichte aus jener düstern Zeit etwas mehr wissen, setzen ihn einstimmig an den Platz der Rittern. In einem kleinen Garten, zur Seite des Ritterpallastes ist ein altes Gemäuer, das sich jetzt an die übrigen Wohnungen und Mauern anschließt, unten mit einer fürchterlich vergitterten Eisenwehr versehen, und mit seinen dickten Mauern tief in die Erde hinablausend; jetzt schlang ein blühender Pfirsich seine Zweige an ihm empor. Dies nennen die meisten das letzte Ueberbleibsel jenes Schreckenthurms, und es hat freilich ganz die Miene desselben und seine grauen und bemoosten Steine widersprechen auch dem Rufe nicht. Ich sah ihn mit Grausen, an Ugolinos Teufelsmahl denkend und ging fürbass.

Reisen durch einen Theil Teutschlands, Ungarns, Italiens und Frankreichs (1801)

Ernst Moritz Arndt (Schoritz 1769-Bonn 1860) è stato uno scrittore e politico tedesco. Di umili origini, studiò teologia e storia a Greiswald (1791), per poi passare all’Università di Jena nel 1793. Nel 1798 cominciano le sue peregrinazioni in giro per l’Europa, da cui trarrà un ricco resoconto, poi pubblicato in sei volumi tra il 1801 e il 1803 con il titolo Reisen durch einen Theil Teutschlands, Ungarns, Italiens und Frankreichs in den Jahren 1798 und 1799. Dell’Italia, di cui visitò solo il Settentrione e la Toscana, apprezzò le tracce rinascimentali e il carattere degli abitanti che, nella sua ottica romantica e nazionalistica, erano riusciti a conservare la propria autonomia nonostante secoli di giogo straniero. Aspramente critico nei confronti della Rivoluzione francese, dei suoi fondamenti filosofici, nonché dei suoi esiti politici, tra il 1803 e il 1808 pubblicò una serie di opere a carattere storiografico, nelle quali espose la sua dottrina politica: se da un lato a fondamento del principio di umanità vi è il concetto di patria, il suo auspicio è il ripristino di una civiltà germanica a trazione prussiana e austriaca, che dia vita ad un vero e proprio impero tedesco. Fu tra i più accaniti promotori di una guerra patriottica e di popolo contro la Francia napoleonica, cui contribuì con le sue composizioni poetiche che ebbero vastissima eco tra il 1812 e il 1813. Di idee liberali, fu estromesso dall’insegnamento all’Università di Bonn nel 1818. Riottenne l’incarico solo nel 1840, mentre l’anno successivo fu nominato rettore da Federico Guglielmo IV di Prussia. Alla sua morte, nel 1860, gli venne dedicato un monumento nell’isola di Rügen.

Nel marzo del 1799 Arndt è a Pisa. Della città fa un’ampia e dettagliata descrizione, non priva di annotazioni critiche. Come per tutti i visitatori di gusto romantico, l’Ordine dei cavalieri di Santo Stefano perde centralità (Arndt ne ricorda la fine della dimensione militare da poco sancita da provvedimenti di Pietro Leopoldo I di Toscana). La stessa Piazza dei Cavalieri è trattata dal visitatore quasi con sufficienza: se il Palazzo della Carovana adorno dei «sei busti di principi medicei» è «un edificio molto imponente», nella statua di Cosimo I (di cui ricorda l’iscrizione dove è riportato il nome di Ferdinando I de’ Medici, terzo granduca di Toscana) e nella fontana «non vi è niente di eccellente». Il visitatore tedesco non risparmia le sue critiche neppure ai dipinti (tra cui le due pale di Bronzino e Vasari) conservati nella chiesa di Santo Stefano, giudicati «mediocri». Quello che invece affascina Arndt è il ricordo dantesco dell’episodio di Ugolino e della sua prigionia nella Torre della Fame. Sebbene si possano rinvenire alcune imprecisioni nella sua ricostruzione (sarebbe forse più opportuno porre la congiuntura che descrive sei anni dopo, nel 1288), va dato il merito allo storico tedesco di essere uno dei pochi visitatori stranieri a ricollocare correttamente la Torre della Fame in Piazza dei Cavalieri. Poco male se un sovrappiù di fantasia romantica gli faccia scorgere le ultime tracce della struttura in un rudere da collocarsi probabilmente alle spalle dell’attuale Palazzo dell’Orologio. Nel 1799, infatti, da quasi due secoli la torre era stata totalmente assorbita in questo edificio, oggi sede della Biblioteca della Scuola Normale, allora adibito a residenza per i cavalieri anziani dell’Ordine di Santo Stefano.

1822

Leigh Hunt

Further up on the same side of the way, is the old ducal palace, said to be the scene of the murder of Don Garcia by his father, which is the subject of one of Alfieri’s tragedies: and between both, a little before you come to the old palace, is the mansion before mentioned, in which he resided, and which still belongs to the family of the Lanfranchi, formerly one of the most powerful family in Pisa. They were among the nobles who conspired against the ascendancy of Count Ugolino, and who were said, but not truly, to have wreaked that revenge on him and his children, recorded without a due knowledge of the circumstances by Dante. The tower in which Ugolino perished was subsequently called the Tower of Famine. Chaucer, who is supposed to have been in Italy, says that it stood «a little out» of Pisa; Villani says, in the Piazza of the Anziani. It is understood to be no longer in existence, and even its site is disputed.

Leigh Hunt (Southgate 1784-Putney 1859) was an English journalist, poet, and essayist. He debuted his verses at a very young age with the collection Juvenilia, published in 1801, demonstrating his remarkable ability to emulate Italian metrical forms. In 1808, he began his career as a journalist and co-founded the weekly Examiner with his brother John. Through this publication, they launched a series of liberal-inspired political campaigns and published fierce critiques of the Prince Regent, which ultimately led to their imprisonment in 1813. As a literary and art critic who advocated for Romantic principles, he maintained close friendships with major literary figures of his time, including John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley, whose works he helped disseminate. According to his Autobiography (1850), at Shelley’s suggestion, Hunt travelled to Pisa in 1822 to launch The Liberal with Byron, a venture that foundered after only four issues. His passion for Italy was expressed not only through his Tuscan sojourns and metrical experimentation (noteworthy is his 1848 volume on Sicilian pastoral poetry) but also in the production of several significant works, including the poem The Story of Rimini (1816).

His observations about Pisa appear in several pages of The Liberal as well as in his Autobiography, where, in keeping with the conventions of this literary genre, Hunt often indulges in impressionistic, personal reflections, ranging from the appearance of Pisan citizens to the purity of their language. It is interesting to note how, in Hunt’s personal topography, Piazza del Duomo is relegated to an almost secondary visit, completely detached from the urban context. The English writer’s emphasis (followed in this by his Romantic colleagues) shifts instead to the Lungarni and a special itinerary shaped more by adventurous curiosities and literary reminiscences than by the history of the places. Thus we find references to Palazzo Lanfreducci, notable for its famous yet mysterious motto ‘Alla giornata’ still visible on its façade; the ‘old ducal palace’, once Cosimo I’s first Pisan residence and now the Prefecture headquarters, which served as the setting for a scene in Vittorio Alfieri’s Don Garzia; and Palazzo Toscanelli, now the State Archives, remembered chiefly as the residence of Lord Byron (and Hunt himself). The sixteenth-century Vasarian Piazza dei Cavalieri is forgotten: what keeps its memory alive is still the Dantesque myth (supported by two medieval sources – Chaucer and Giovanni Villani) of Ugolino della Gherardesca and the Tower of Famine. Though he engaged with the pastoral – an eminently Baroque genre – through his 1820 translation of Tasso’s Aminta, Hunt’s democratic and liberal politics and his Romantic sensibilities aligned him more closely with medieval and late Enlightenment traditions.

1827

Antoine-Claude Pasquin (Valéry)

While they may lack the prominence and splendour of the Cathedral and the Baptistery of San Giovanni, many churches in Pisa are nonetheless worthy of attention. Among them, the magnificent church of Santo Stefano—belonging to the Knights of the Order of Saint Stephen—recalls their noble history. Several old flags, taken from the Muslims, hang from the vault, bearing witness to the Knights’ valour more eloquently than the paintings and Latin inscriptions that accompany them. [Footnote: ‘These paintings include the Capture of Bona; the Capture of Nicopolis, by Jacopo Ligozzi; a Naval Victory of 1602; the Marriage of Maria de’ Medici with Henry IV—somewhat oddly placed among these various triumphs over the infidels—by Empoli; another Naval Victory made in 1571 by Cigoli; and Cosimo I Receiving the Knight’s Habit, by Cristofano Allori].

The high altar is striking in its opulence, though it belongs to a later period of decline. Among the paintings displayed on the altars are The Martyrdom of the Saint by Vasari, notable for its dry and cold colouring but skilful composition; Christ Carried to the Tomb by His Disciples and the Marys by Gambara, a work both touching and vigorous; a beautiful Nativity by Bronzino; and The Madonna between Saint Joseph and Saint Stephen, Kneeling—a pleasing composition and one of Aurelio Lomi’s finest. The great organ of Santo Stefano is one of the finest in Italy.

The memory of Count Ugolino and the tragedy of his sons still lingers in Pisa—a city marked by its connection to one of the most sublime and renowned passages in Italian poetry. Dante’s verses, together with the horror of Ugolino’s torment, have all but turned this abominable tyrant into a figure of fascination. The Tower of Hunger once stood in what is now Piazza dei Cavalieri; its remains are incorporated into the Palazzo dell’Orologio, a structure formed by two ancient towers joined by an archway. The part closest to the former Conventual Palace was the site of the infamous tower.