Urban Development in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages

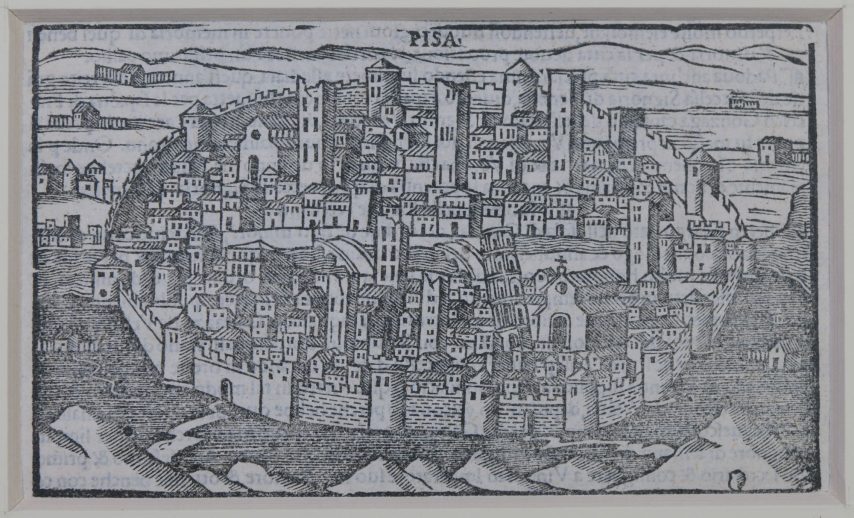

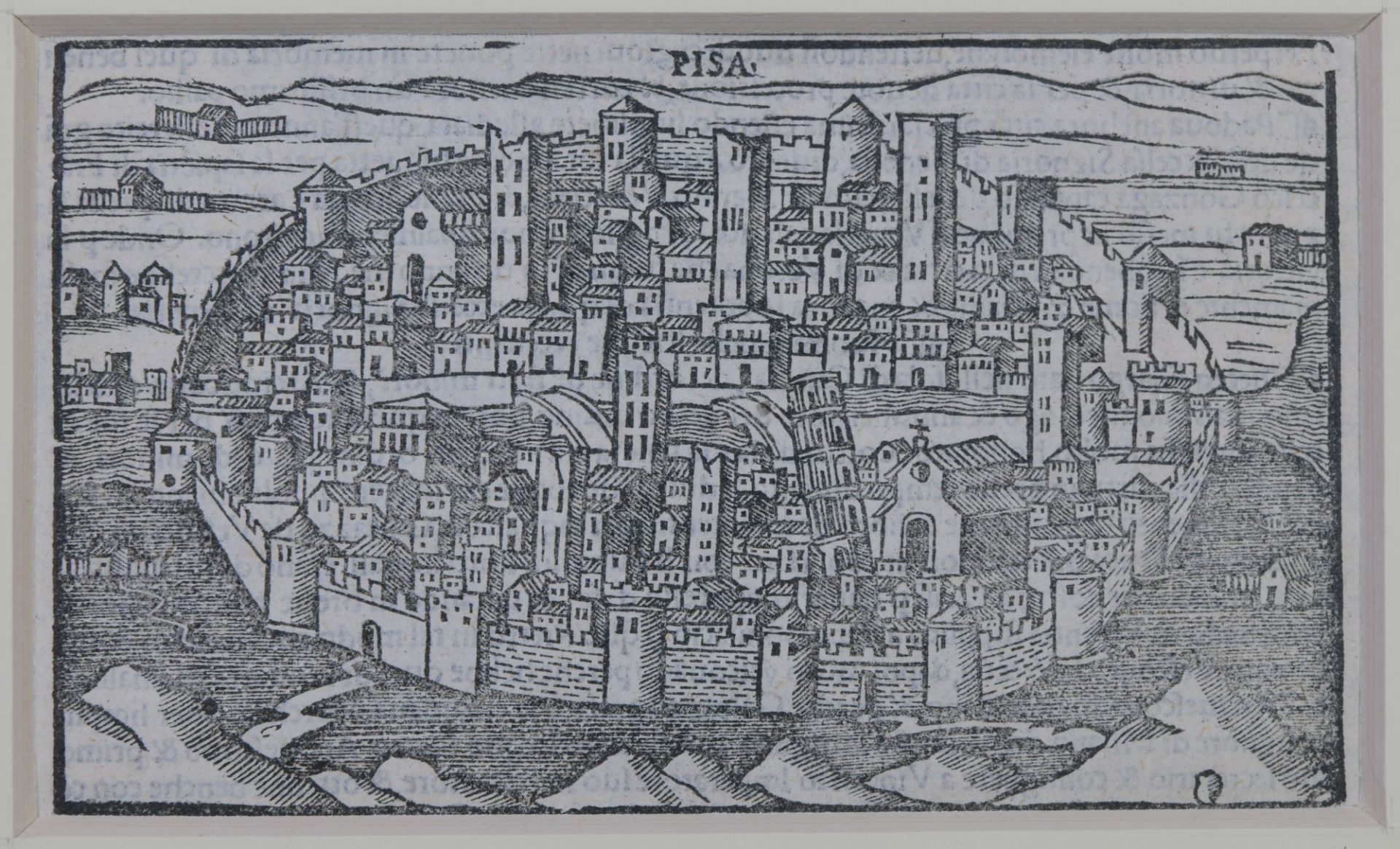

To reconstruct the appearance of the predecessor of Piazza dei Cavalieri—the urban space known as the ‘Sette Vie’ area (a problematic name, given its reference to multiple access routes), or alternatively as Piazza del Popolo, or Piazza degli Anziani—we must rely on written sources, architectural remains incorporated into later buildings, and data from six excavations conducted between 1961 and 2021 in the piazza and adjoining streets, prompted by building projects that required the recording of ancient remains before work could continue.

No archaeological evidence has confirmed the now-outdated hypothesis that Piazza delle Sette Vie was built over an ancient theatre or civic forum. Excavations—particularly those of 1993—have instead established occupation of the site from at least the seventh century BC. A comparison of structural remains in panchina (a local carbonate rock) and foundation deposits, along with evidence from nearby Via Sant’Apollonia, just east of the present block of the Palazzo della Carovana, has led scholars to propose the existence of a sanctuary active throughout the Hellenistic period.

Evidence from the Roman era is more limited. The sanctuary appears to have been abandoned in the first century BC, while the discovery of ornamental statues described by Lucia Faedo in 1993, together with more recent finds from the garden of San Sisto, suggests the presence of domus (residences) between today’s Via Paoli and Via Ulisse Dini. The present piazza, therefore, most likely overlies a Roman residential quarter rather than public structures such as a theatre or forum.

Excavations have revealed the medieval phases of the piazza and its surrounding area. Between the seventh and eighth centuries AD, a clear re-urbanisation occurred, marked by metalworking—particularly iron—attested by the abundant presence of ferrous slag, a defining feature of the early medieval strata. By the late tenth to early eleventh centuries, stone-built structures connected with these activities had appeared, located in front of the façade and along the southern side of what is now the church of Santo Stefano dei Cavalieri.

The area soon developed multiple functions: residential, with the construction of tower houses; religious, with the churches of San Pietro in Cortevecchia and San Sebastiano alle Fabbriche maggiori, documented from 1027 and 1074 respectively; and civic, with the toponym Cortevecchia associated with a seat of political authority. Despite the flooding episodes of the eleventh century, which left distinctive clay deposits, the settlement’s expansion continued, and construction activity lasted until the fourteenth century. At that point, a seemingly opposite trend emerged: the demolition of several tower houses, which was recorded on the piazza.

The date when Piazza delle Sette Vie was first designated as a public space, as well as the extent of the piazza in the Middle Ages, remains uncertain. Recent archaeological soundings have confirmed the presence of buildings, dated between the tenth and fourteenth centuries, beneath the present paving in the following areas:

- The north-east corner of the piazza, between the Tower of Famine and Palazzo degli Anziani;

- In front of the façade of Santo Stefano dei Cavalieri, oriented east–west;

- In front of the present Palazzo della Canonica.

Written sources likewise suggest that the piazza was much smaller than it is today, recording expropriations and demolitions of houses between the late thirteenth and the first half of the fourteenth century. It was during this period that this urban area appears to have expanded and stabilised, with the laying of uniform brick paving in a herringbone pattern. These works, undertaken under the lordship of Count Fazio da Donoratico, may be those referred to in the anonymous Cronica di Pisa preserved in the Roncioni manuscript after 1337: ‘lo conte Fatio, per ben guardare la cità, fecie fare molti edifici e fecie acresciere la piassa delli Ansiani’ [Count Fazio, to safeguard the city, had many buildings erected and enlarged the Piazza degli Anziani].

Expropriations, demolitions, and repaving constituted a wide-ranging urban intervention that, by the mid-fourteenth century, signalled the consolidation of the Comune di Popolo (Popular Commune’s) seat of power. The first element was the Palazzo degli Anziani, followed by the Palazzo del Capitano del Popolo (from 1327), the Camera nuova del Comune (1338), and several annexed buildings. These, originally private domus, were later rented or purchased by the Commune to accommodate a variety of functions: prisons in the Tower of Famine; lodging for the marabesi(poor clerics of the cathedral chapter) in towers near San Sebastiano; storage for the hay destined for the beds of the captives; and, according to one hypothesis, even a shelter for a lion owned by the Commune.

From the thirteenth century, with the establishment of the administrative centre of the Popular Commune, Piazza delle Sette Vie stood at the heart of the city’s political life. Written sources, though fragmentary, hint at the new functions attributed to this space during the period.

Above all, the ‘Sette Vie’ area functioned as a stage for the Commune’s self-representation, rich in symbolic significance. On 26 June 1314, a victory over Lucca was celebrated there with a bonfire of firewood bundles. As the anonymous author of the Cronica recounts, in 1362 the Corpus Domini procession passed through the piazza, with the solemn participation of the Anziani, and in 1381 a celebratory procession marked the knighting of Andrea Gambacorta. In 1383, however, the continuing plague (the morìa) prompted the Commune to bring the relics of Saint William of Maleval into the city. After an initial display in the Cathedral, they were carried to the piazza and into the Palazzo degli Anziani ‘with the greatest reverence.’

Alongside these displays of unity, Piazza delle Sette Vie also served as the stage for episodes of discord and sharp political conflict. These ranged from the well-known capture and imprisonment of Count Ugolino in 1288, vividly recounted in the Fragmenta historiae pisanae, to the rebellion of Ceo and Benedetto Maccaione Gualandi against the regime of Count Fazio in November 1335. On this latter occasion, access to the piazza was reportedly closed to the rebels.

In 1355, Charles IV sought to quell the factional conflicts between the Raspanti and Bergolini, initially holding separate negotiations in the churches of San Pietro in Cortevecchia and San Sisto, then assembling all parties in Piazza degli Anziani to demand peaceful coexistence. This effort failed, and a few months later, by order of Charles IV, the affair ended in the same piazza with the beheading of seven members of the Bergolini faction at the foot of the steps to the Palazzo degli Anziani.

These are only some of the most spectacular events recorded in the medieval Pisan chronicles, reflecting the intense political life that centred on the piazza until the end of the Commune.

Media gallery

Newsletter

Stay in Touch

Sign up for the Piazza dei Cavalieri newsletter

to receive updates on project progress and news.